Yesterday morning, we had a very interesting “teaching breakfast” as part of #CoCreatingGFI: Anja Møgelvang introduced us to Cooperative Learning. Anja is a PhD student at the Center for Excellence in Biology teaching BioCEED, and in addition has 15 years of experience in high school teaching, and 5 in teacher education, so who better suited to talk about this?

Cooperative Learning (CL) is a highly structured method (and not to be confused with the much less structured collaborative learning) – the teacher sets very clear rules around how groups form, how students work together in groups, how tasks are structured and shared. The goal is to create “positive interdependence”, i.e. structuring groups and tasks in such a way that students depend on each other in order to complete the assignments, and on “individual accountability”, i.e. making sure that there is no social loafing.

This is facilitated by

- making it very explicit to students why CL is used as a form of learning: even though there are challenges with group work (see below), most rewarding things are difficult and this form of learning has many benefits in addition to deep learning of content knowledge and skills, for example for critical thinking, problem solving, communication skills

- acknowledging that groupwork is difficult, and explicitly addressing challenges and giving time for collaborative development of group rules (or even requiring written group contracts to deal with problems like members not meeting deadlines, not showing up to meetings, disagreements within the group)

- being clear about the role of the teacher in all of this

All of this contributes to students taking ownership for their own learning.

Groups ideally consist of 3-5 students (4 are perfect because they can work as two pairs, and in any case these groups are small enough to minimize free riding and encouraging even shy members to speak, while at the same time providing enough different view points). For best results and inclusion, the teacher forms student groups to be diverse in terms of student background, age, gender, academic ability, etc.. Groups work together long-term (at least half the semester) to give students enough time to really connect with the other group members.

Time and tasks are also highly structured: Large tasks are divided into sub-tasks so students know exactly where to start and what to do (Maybe even assign a number of minutes to each task so it is very clear where students are supposed to be at at any given time; but of course adjust as necessary!). Moving from one task to the next can be signalled for example by switching the lights on and off repeatedly, so the teacher doesn’t need to shout over lively discussions.

Students also know exactly where to sit with their group, in a lecture theatre for example two students in the row just behind the two other students from their group, so that the first row just needs to turn around for all four of them to work together.

To facilitate the group work, either the teacher or the student themselves can agree on roles (coordinator, moderator, fact-checker, devil’s advocate, image creator, statistics person, …). It is important that these roles rotate through the group to a) make sure that all students get the chance to practice all skills, and b) no hierarchy develops based on the perceived importance of different roles. Roles must of course be adapted to the context and task, and students need to perceive them as having a purpose, otherwise they won’t engage.

While group work is going on in a physical setting, as a teacher it is helpful to roam the room to keep an overview over what is going on in the different groups. In all settings, a teacher can tell students that they will randomly call on one student from each group to present, ensuring that all students in the group will prepare to be called upon and don’t get cold-called.

To make the most of CL, it needs to be integrated throughout the course. So for example, there might be short discussions in lectures about what needs to be done within each group for the upcoming seminar, in the seminar the groups might prepare for a lab, etc..

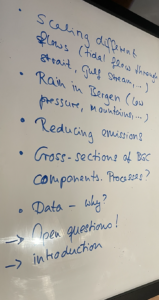

So what could look CL look like in practice, in our context at GFI?

Anja shared two methods with us, and at my table we worked on the “send a problem” method: Student groups receive an envelope on which a problem/question is stated. They work on it, put their responses into the envelope, and send the envelope on to another group that worked on a different but related problem. After three rounds of this, students have worked on solving three different problems without seeing other groups’ attempts, and in the fourth round receive an envelope with yet another new problem, and three other groups’ attempts at solving it. In this round, students then compile and present the collective solution.

We discussed where this might be applicable in our context, and came up with several ideas in the courses of the teachers at my table: Students could get data and work on what processes have to be at play to lead to this kind of data. Or they could work on suggestions to reduce carbon emissions. Or they could get images of different #WaveWatching situations and discuss the relevant processes in the image (and this wasn’t even my suggestion!).

We discussed where this might be applicable in our context, and came up with several ideas in the courses of the teachers at my table: Students could get data and work on what processes have to be at play to lead to this kind of data. Or they could work on suggestions to reduce carbon emissions. Or they could get images of different #WaveWatching situations and discuss the relevant processes in the image (and this wasn’t even my suggestion!).

At another table, the method was “dyadic essay confrontations”: Students develop questions and model answers, questions are swapped, and other students respond, and then the owner of the question corrects their response and give feedback. This can work super well in exam preparation when students are working together in groups anyway and are asked to imagine what exam questions could look like! This could work especially well when they know that one or several of the questions they develop and work on will actually end up on the exam!

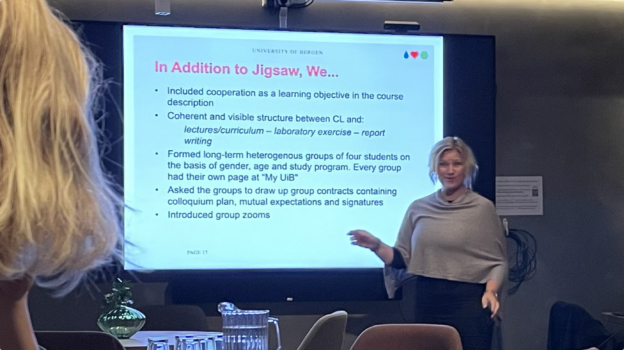

Anja ended the workshop by presenting results from her (pandemic, hence online) PhD studies: There, they used the “jigsaw” method. Students belonged to “home groups” but from there pick topics they are most interested in and want to become experts on: they both learn about those topics and think about how to teach them in new “expert” groups. They then go home into their home groups, where they synthesize all the new information into a shared product. Anja found in her study that during the periods where students were working using this method, the students’ perceived generic skills, science confidence, and sense of belonging increased significantly (higher than what students expected to feel, and higher than before and after, for sense of belonging), as compared to digital lectures.

At the same time, loneliness was much lower during the phases the method was used (again, lower than what students expected!) – very important during the very lonely period of spring 2021, and generally an important consideration in online teaching. So not only are the methods fun and lead to better learning, they also work on really important psychosocial factors! So how could we not want to try them?

Pingback: Structuring fieldwork as a jigsaw to increase student responsibility in, and ownership of, their projects - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching

Pingback: Currently reading about cooperative & collaborative learning (Oakley et al., 2004; Møgelvang, 2023; Wieman et al., 2014) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching

Pingback: Currently reading about how to successfully organize team work in student groups - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching