Reducing bias and discrimination in teaching: an annotated, incomplete — WORK IN PROGRESS! — list of references

Already at the time of posting, I have added to my to-read list for an updated version of this post. Please let me know of any additional literature I should include, and of any other comments you might have! As it says in the title, this work is incomplete and in progress!

“The rights perspective, which is also called the justice or democracy perspective, means that everyone should have the right to the same education and career. Gender – or other “dividing categories” – should therefore not affect career opportunities. The research system perspective emphasizes the importance of finding the best people for research, while the socio-economic perspective points out that it is a waste of public resources not to make use of the most suitable candidates. Finally, the epistemological perspective focuses on the fact that increased diversity among researchers leads to greater diversity and thus to better quality in research.” (translated after Schnaas, 2011)

There are many reasons for why we should strive to reduce bias in academia. This is a collection of references I curated for their relevance regarding creating conditions in which students can focus on learning rather than their gender, race, sexuality, disability, … and where biases regarding student identities are reduced. This document is incomplete (the focus right now is very much on gender; but I am assuming that a lot of the findings are probably transferrable to other minorities, and I will look into that literature in the future).

To make this collection relevant in the context of my work at LTH, I have included articles from the “LTHs pedagogiska inspirationskonferens” data base. I used the search terms (on 1.4.2022) “bias” (0 results), diskriminering (1), discrimination (1), “gender” (6), “genus” (1), “kön” (2), mångfald (0), UDL (2). Some of these articles were not relevant to this topic, others included several of the search terms. In the text, sources from LTH are highlighted as such, and are linked to directly from the text.

The intent of this document is not that everything mentioned here be included in all academic development courses I teach, rather it gives us “aces up our sleeves” that we can bring in if/when appropriate.

The structure of this document follows the main topics of the “Introduction to Teaching and Learning in Higher Education” course at LTH (NOTE: THE LINKS BELOW ONLY WORK IF YOU LOOK AT THE EXPANDED VERSION OF THE BLOGPOST!):

The student

– Who are we trying to communicate with?

– LTH’s students’ stereotypes of “typical engineers” are different from how they see themselves (Soneson & Torstensson, 2013)

– Research in learning and teaching is done on a sample that might not be relevant in all contexts

— Almost exclusively WEIRD (Henrich et al., 2010)

— Often male-dominated, with a binary understanding of gender, where the achievements of men are used as the gold standard (Traxler et al., 2016)

– Gender-based discrimination does exist

— #metoo in Sweden: #akademiuppropet (Salmonsson, 2020)

— #metoo at Lund University (Agardh et al., 2020)

— #metoo at LTH (Wrammerfors, 2018)

— Almost 4 in 5 female students experience sexual harassment at least once a year and that affects their motivation to study STEM subjects (Leaper & Starr, 2019)

— Increasing awareness about gender discrimination and sexual harassments helps women realize that it is not their fault that they are being targeted (Weisgram & Bigler, 2007)

– Female and male students attribute their own performance in different ways (Beyer, 1998)

— Physical science career interest is supported by discussion of underrepresentation of women (Hazari et al., 2013)

Student learning

– Students achieve more when they believe that they can develop their abilities, and we can influence that (Yeager & Dweck, 2012)

— Even non-feedback comments can influence student mindset and performance (Smith et al., 2018)

— Activating stereotypes can trigger student underperformance (Steele, 2011)

– Intersectionality: Some students belong to several disadvantaged categories simultaneously (Phoenix & Pattynama, 2006)

– There is a tendency for teachers to explain performance based on the student’s gender (Espinoza et al., 2014)

Course design

– Everybody should be able to participate

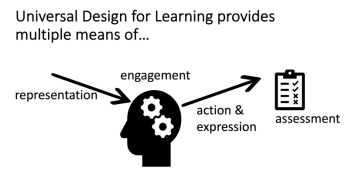

— Making learning accessible for everyone: Universal design for learning (Brand et al., 2012)

— Decisions on accommodations due to disabilities are often biased against specific disabilities (Druckman, 2021)

– Choosing learning outcomes, materials & physical space wisely

— Learning outcomes and examples might not appeal to everyone in the same way (Stadler et al., 2000)

— Textbooks and other materials can perpetuate (and activate) stereotypes (Taylor, 1979)

— Including (narratives of) role models for everyone can balance stereotype threat (McIntyre et al., 2003)

— Make sure to include all relevant voices (“Decolonizing the curriculum”; Dessent et al., 2022)

— The physical environment influences who feels welcome and participates (Cheryan et al., 2009)

Learning activities

– Participation matters, and there is a gender gap

— The person who speaks most, not who makes the best points, emerges as leader (MacLaren et al., 2020)

— There is a gender gap in participation in Scandinavia (Ballen et al., 2017)

– Active learning can help reduce gaps

— Interactive engagement reduces gender gap in physics (Lorenzo et al., 2006)

— “Reductions in achievement gaps only occur when course designs combine deliberate practice with inclusive teaching” (Aguillon et al., 2020; Theobald et al., 2020)

— Women like the connections provided by PBL (Reynolds, 2003)

– Students working in small groups

— Optimal group size for (physics) problem solving is three (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

— High-ability groups don’t always perform best (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

— Male students ignore female students’ input to their own detriment (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

— When assigning groups, cluster minorities rather than stretching them across as many groups as possible (Stoddard et al., 2020)

— “Women-only exercise groups” sometimes recommended by teachers at LTH

– Focussed sessions (interventions) can help decrease achievement gaps

— Help students see that they belong in the classroom and that adversity is normal, temporary, and surmountable (Cohen et al., 2006; Hammarlund et al., 2022)

— Help students remember their values (Martens et al., 2006; Cohen et al., 2009; Mijake et al., 2010)

Communication

– Global English (Aarup Jensen et al., 2017)

– If you are new to the Swedish educational system, be aware of cultural differences (Natalle, 2012)

– It matters to students that teachers make an effort to know their names (Tip: name tents!) (Cooper et al., 2017)

– Sensitive language

— Gender-sensitive communication

— Preferred gender pronouns

— Disability-sensitive communication

— Questionable terminology and better alternatives

– When and how to address issues of diversity and inclusion in teaching (when it is not the topic of the course)

— Examples of gender and equality sensitive situations in teaching

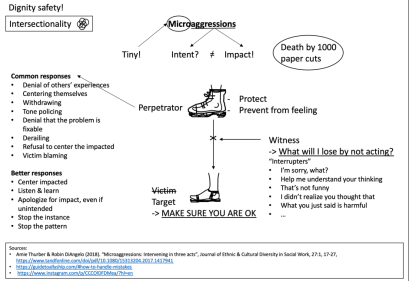

— Interrupting microaggressions (Thurber & DiAngelo, 2018)

— Purposefully observing gender-relevant situations: “genusobservatörer” (Carstensen, 2006)

— What kind of resistance to expect when gender becomes a topic of conversation (Carstensen, 2006)

— “Harassment” is a really tricky (and potentially not helpful) concept (Carstensen, 2016)

Assessment

– It matters who gives an exam because it can activate stereotype threats (Marx & Roman, 2002; Marx & Goff, 2005)

– If you have to ask about demographics, do it after the test so you don’t activate stereotype threat (Danaher & Crandall, 2008)

– Multiple-choice questions and gender bias

— Multiple choice questions vs constructed response questions (Weaver & Raptis, 2001)

— Negative marking for multiple-choice questions (Funk & Perrone, 2016)

— Women are more conservative and timid test takers than men (Pekkarinen, 2015)

The teacher

– Your own growth-mindset matters (Hammarlund, 2022)

– Gender bias is everywhere and it is also acting against teachers

– Women have to be better than their male peers to be perceived as equal to them in academic hiring decisions (Eaton at al., 2020)

– Student evaluations of teaching are biased (Heffernan, 2021; but there are ways to use them for good nevertheless! Roxå et al., 2021)

– There is a backlash for men violating gender stereotypes (Moss-Racusin et al., 2018)

– There is documented gender bias at LTH

— Teachers at LTH have, on average, a “Slight automatic association for Male with Science and Female and with Liberal Arts” (Allanson et al., 2021)

— Some teachers at LTH write in ways that suggest that men are superior to women (Berndtsson & Thern, 2012)

– Talking about gender, race, and other prejudices and biases is difficult!

— Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism (DiAngelo, 2018)

— Sometimes “nothing happens” and still something happens (Husu, 2020)

— “Visibility paradox”: women can be simultaneously highly visible and invisible (Husu, 2020)

– Legal aspects: Defamation lawsuits (Damström, 2020)

– What can you do to support equality?

— “Gender mainstreaming” (European Commission, 2000)

— Women: don’t downplay the effects of gender! (Korvajärvi, 2021)

— Men: accept evidence of gender biases in STEM! (Handley et al., 2015)

— Install institutional strategies for gender equity! (Laursen & Austin, 2020)

— Be careful to not write biased letters of references! (Madera et al., 2009)

The student

Who are we trying to communicate with?

It is important to consider who exactly we are meeting at university. They are individuals with different strengths, cultural backgrounds, … This matters for how they approach university, but also for what we can assume as shared basis for communication. Sports metaphors for example are very dependent on which country and also which type of socio-economic environment someone grew up in. But cultural backgrounds don’t only depend on the culture someone grew up in, but also the time when that happened. The Hollywood movie “the day after tomorrow” that came out in 2002 when I was studying oceanography was a great reference in science communication then, but some of our students now, in 2022, were not even born then. That means they for example also don’t remember 9/11 as a lived experience, let alone Chernobyl or earlier events that might be very relevant and present in our memories as teachers.

The easiest solution is to ask students to share some things about themselves (ideally including why you are asking – in order to make your teaching more relevant to them. Otherwise it might seem creepy and students might not be too enthusiastic about engaging)!

There are also surveys done on incoming students, here at LTH every second year. But I have not seen the data, so I cannot reference that here.

LTH’s students’ stereotypes of “typical engineers” are different from how they see themselves (Soneson & Torstensson, 2013)

Students at LTH ascribe a lot of attributes to “a typical engineer” that they themselves claim to not possess to the same extent: Both women and men on average describe themselves as more subordinate, feminine and inferior, and less independent than what they imagine “a typical engineer” would be. Women’s self-images differ more from the stereotype, and especially from women’s own stereotype, which in terms of these characteristics is more extreme than men’s (Soneson & Torstensson, 2013).

Research in learning and teaching is done on a sample that might not be relevant in all contexts

Almost exclusively WEIRD (Henrich et al., 2010)

Psychology and educational research is – at least in English language journals – done on persons that are WEIRD: western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic. “A 2008 survey of the top psychology journals found that 96% of subjects were from Western industrialized countries — which house just 12% of the world’s population” (Henrich et al., 2010).

Educational systems and cultures are also very different in different countries, and a lot of the research is happening in a US context. We therefore have to always consider whether results are likely transferrable to our specific context.

Often male-dominated, with a binary understanding of gender, where the achievements of men are used as the gold standard (Traxler et al., 2016)

In his seminal work on stages of development, William Perry (late 1950ies) had an almost exclusively male sample (because he was working at US Ivy League universities at that time). According to reports that I cannot trace back all the way to his work because I don’t have access, he ended up using only answers by men, because the few female answers were outliers that he couldn’t fit into his theory. Belenky and others then developed an alternative model to Perry’s: “Women’s ways of knowing”. A binary understanding of gender is still the basis of research in the field today.

A lot of physics (and other science) education research has used a binary gender deficit model, which “casts gender as a fixed binary trait and suggests that women are deficient in characteristics necessary to succeed.”

This is problematic because “(i) it does not question whether the achievements of men are the most appropriate standard, (ii) individual experiences and student identities are undervalued, and (iii) the binary model of gender is not questioned.” (Traxler et al., 2016)

Gender-based discrimination does exist

#metoo in Sweden: #akademiuppropet (Salmonsson, 2020)

#Akademiuppropet (“the academic petition”) grew out of a private Facebook group where Swedish female university staff collected and discussed experiences. It grew to 9,000 members within only two weeks, at which point it was closed down to protect members’ privacy. The resulting petition was based on 100 personal narratives of experiences of sexual harassment at Swedish universities and was signed by 2,648 people who then, or previously, worked at Swedish universities. The petition was published in Svenska Dagbladet in 2017 as well as handed over to the minister of education. It prompted political measures for universities to prevent sexual harassment.

#metoo at Lund University (Agardh et al., 2020)

In response to the #metoo movement, a working group at Lund University wrote a baseline report on sexual harassment and discriminatory treatment:

https://tellus.blogg.lu.se/files/2020/09/Tellus-sexuella-trakasserier-trakasserier-och-krankande-sarbehandling.pdf (Agardh et al., 2020)

#metoo at LTH (Wrammerfors, 2018)

There is an internal “Rapport om sexuella trakasserier på LTH”.

Almost 4 in 5 female students experience sexual harassment at least once a year and that affects their motivation to study STEM subjects (Leaper & Starr, 2019)

In a biology class in the US, more than 3 in 5 female students experienced gender bias, and more than 4 in 5 experienced sexual harassment, at least once in the past year, from either classmates or instructors. This is, not surprisingly, detrimental to female students’ motivation (Leaper & Starr, 2019). Women and girls in STEM are often unaware how widespread this is (and boys and men probably even more so).

Increasing awareness about gender discrimination and sexual harassments helps women realize that it is not their fault that they are being targeted (Weisgram & Bigler, 2007)

Female students tend to blame themselves for being targets of harassment. Increasing awareness of how widespread harassment is, and to how many other people it is happening, too, helps them realize that it is not their fault. It also lets them reinterpret previous struggles or performances – both their own and other females’ – in this new light (Weisgram & Bigler, 2007; Leaper & Starr, 2019). Knowing about other women’s struggles with discrimination and harassment, and how they have overcome them, helps female students to feel more agency and self-efficacy related to their careers (Weisgram & Bigler, 2007).

Female and male students attribute their own performance in different ways (Beyer, 1998)

Female and male students typically explain their successes and failures differently. Male students attribute success to their abilities, whereas failure is blamed on a lack of interest and effort. Female students attribute success to having worked hard, and they have positive emotional responses (pride and happiness) to success. However, female students attribute failure to lack of ability, which leads to generally feeling like a failure, and to worries about the future, which has negative consequences for female students’ self-esteem. (Beyer, 1998)

Physical science career interest is supported by discussion of underrepresentation of women (Hazari et al., 2013)

Typical measures to keep women in physics are to “(i) having a single-sex physics class, (ii) having a female physics teacher, (iii) having female scientist guest speakers in physics class, (iv) discussing the work of female scientists in physics class, and (v) discussing the underrepresentation of women in physics class. The effect of these experiences on physical science career interest is compared for female students who are matched on several factors, including prior science interests, prior mathematics interests, grades in science, grades in mathematics, and years of enrollment in high school physics. No significant effects are found for single-sex classes, female teachers, female scientist guest speakers, and discussing the work of female scientists. However, discussions about women’s underrepresentation have a significant positive effect.” (Hazari et al., 2013)

Student learning

Students achieve more when they believe that they can develop their abilities, and we can influence that (Yeager & Dweck, 2012)

It is important that students believe that they can overcome challenges through good strategies, hard work, learning new skills, help from others, and that it takes patience. Such a “growth mindset” helps them persist and show higher achievement in challenging situations. A growth mindset can be taught for example by modelling overcoming of challenges, and by pointing out that success is not due to traits, but rather due to effort. There are also growth mindset interventions (see below) that have shown good results (Yeager & Dweck, 2012).

Even non-feedback comments can influence student mindset and performance (Smith et al., 2018)

Even non-feedback related teacher comments, for example about a subject or a course in general (in the article, they give the examples of “not everyone is good at statistics” vs “everyone can learn statistics if they try”; and “sorry no time for questions” vs “please ask questions”), can influence students’ mindset towards a growth mindset, and thus influence their performance (Smith et al., 2018).

Activating stereotypes can trigger student underperformance (Steele, 2011)

When students are in a setting in, or doing an activity for which a negative stereotype for their group (or groups, see intersectionality!) applies, they will need energy to deal with knowing that others might react to or perceive them based on that stereotype, and to counteract reinforcing that stereotype. This energy is not available for performance, which leads to systematic underperformance of those students. This is called the “stereotype threat” (Steele, 2011), and it is important that we make sure to not accidentally activate stereotypes.

Intersectionality: Some students belong to several disadvantaged categories simultaneously (Phoenix & Pattynama, 2006)

Intersectionality describes that people belong to many different “categories” simultaneously, based for example on gender, sexuality, race, age, first language, parents’ education level, parents’ income, and many more. Some of these facets come with privileges, others don’t. Some people are disadvantaged based on their belonging to several categories at once. “Fruitful knowledge production must treat social positions as relational” (Phoenix & Pattynama, 2006)

There is a tendency for teachers to explain performance based on the student’s gender (Espinoza et al., 2014)

Teachers tend to explain performance of girls and boys differently: “Whereas boys’ successes in math are attributed to ability, girls’ successes are attributed to effort; conversely, boys’ failures in math are attributed to a lack of effort and girls’ failures to a lack of ability.” (Espinoza et al., 2014) Interventions can change this teacher behavior, but teachers relapse after about a year (so not doing this requires persistent awareness and effort!).

Course design

Everybody should be able to participate

Making learning accessible for everyone: Universal design for learning (Brand et al., 2012)

Instead of making accommodations when they are needed for individuals (which means that students might have to declare “invisible” disabilities or difficulties to you that they might not be comfortable making public), there are four main principles that can be incorporated to make all parts of the learning process accessible to all learners (Brand et al., 2012):

Multiple means of representation: Provide content it in multiple formats so it can be accessed using different senses, and tailored to specific needs.

Multiple means of engagement: Provide multiple entry points, perspectives, etc. to motivate both initial and sustained student engagement with the content.

Multiple means for action and expression: Give students different options to physically manipulate and communicate about the content.

Multiple means of assessment: Test student understanding in different ways / give them options to choose.

Read more about my thoughts on UDL on my blog: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2022/01/31/thinking-about-universal-design-for-learning/

Rydeman et al. (2018) give LTH-specific experiences and advice on “how can we make teaching more inclusive?” with a focus on dyslexia: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21243

Hedvall, P.-O., Mattsson, P. (2021) suggest “Introducing Norm Creative Perspectives in Engineering and Design Educations” at LTH, with a focus on the question of who designs, who benefits, and who loses: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/23847

Decisions on accommodations due to disabilities are often biased against specific disabilities (Druckman, 2021)

When decisions about accommodations due to disabilities are made, there is often a disability-specific bias: for example, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is often taken less seriously than vision impairment. The decisions about accommodation often include elements of how “deserving” students are based on disability and perceived work ethic.

Choosing learning outcomes, materials & physical space wisely

Learning outcomes and examples might not appeal to everyone in the same way (Stadler et al., 2000)

“Girls seem to think that they understand a concept only if they can put it into a broader world view. Boys appear to view physics as valuable in itself and are pleased if there is internal coherence within the physics concepts learned” (Stadler et al., 2000)

LTH, Fuentes et al. (2005) also recommend making exercises more applied so they become more relevant to female students: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20936

Textbooks and other materials can perpetuate (and activate) stereotypes (Taylor, 1979)

Even “objective” subjects – like physics – are often not represented in a gender-neutral way (for example using “he” instead of she/they; disproportionate numbers of diagrams, illustrations, examples using men or examples typically associated with men; gender role stereotyping (“men as welders, women as nurses”)) (Taylor, 1979)

This is an old reference, but how much better has it really gotten since? I have personally experienced slides with horrible gender stereotypes this year in a course that I have taken at LTH.

Including (narratives of) role models for everyone can balance stereotype threat (McIntyre et al., 2003)

Telling women about other women’s achievements or having them read about individual success stories helps them perform better and not be hindered by stereotype threat (McIntyre et al., 2003). This probably also holds for other minorities.

Make sure to include all relevant voices (“Decolonizing the curriculum”; Dessent et al., 2022)

Curricula are very much shaped by academic traditions, that include some and exclude many other voices. For (a very unspectacular and unimportant) example, when studying oceanography in Hamburg, it is very easy to come to believe that all relevant work has been done there, or at least in collaboration with them. When you move to Kiel or Bergen, it turns out that all the relevant work was done there, or with them. Decolonizing the curriculum means to “develop a more complete scientific perspective that better includes global voices.” (Dessent et al., 2022) and recognize and reflect that not all relevant work has exclusively been done in Europe or the US.

Some of my thoughts here: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2022/01/14/thinking-about-decolonising-the-curriculum-inspired-by-dessent-et-al-2022/

The physical environment influences who feels welcome and participates (Cheryan et al., 2009)

Physical environments that do not activate stereotypes (for example in computer sciences having nature posters on the wall instead of featuring masculine stereotype Star Trek poster and video games) boosts female sense of belonging and interest in the subject to the level of their male peers. This is true even when there are only women around. “Objects can thus come to broadcast stereotypes of a group, which in turn can deter people who do not identify with these stereotypes from joining that group.” (Cheryan et al., 2009)

Learning activities

Participation matters, and there is a gender gap

“A significant gender gap in participation is a problem in the classroom. Those who speak in class exert larger influence on their peers, and the normalization of men speaking significantly more than women in science at the undergraduate level may influence what males and females consider ‘normal’ interaction between scientists farther along the academic pathway: in lab meetings as graduate students, at conferences as postdocs, and in departmental seminars as faculty. The causes and consequences of this demonstrated gap will require further investigation, but may have lasting impacts on females’ scientific identity and long-term decision to remain in science.” (Ballen et al., 2017)

The person who speaks most, not who makes the best points, emerges as leader (MacLaren et al., 2020)

“Speaking time retains its direct effect on leader emergence when accounting for intelligence, personality, gender, and the endogeneity of speaking time.” (tested on students who were there for extra credit (but the extra credit did not depend on outcome of groupwork)) (MacLaren et al., 2020)

There is a gender gap in participation in Scandinavia (Ballen et al., 2017)

“In Norway, like the United States, women’s voices are underrepresented in the classroom. Thus, we are the first study to suggest that despite a relatively gender equal society, women still face similar academic challenges as women elsewhere in the world”, (Ballen et al., 2017)

Active learning can help reduce gaps

Interactive engagement reduces gender gap in physics (Lorenzo et al., 2006)

Lorenzo et al. (2006) find different useful strategies to reduce the gender gap in physics, for example making sure that class picks up on all students’ everyday interests and experiences, students’ prior knowledge is integrated in future learning, there is room for interactions between students and instructor, there are multiple valid ways to engage with content and of assessment, activities are not focussed on competition but on building understanding, and stressing the real-world use of the taught concepts.

“Reductions in achievement gaps only occur when course designs combine deliberate practice with inclusive teaching” (Aguillon et al., 2020; Theobald et al., 2020)

Even though active learning has shown to decrease the achievement gaps of minorities in STEM, this unfortunately does not happen automatically just by using active learning methods. Deliberate practice (i.e. using evidence-based teaching methods, like scaffolding so students can build their understanding step by step and practice specific skills, providing feedback often and immediate, and building in repetition) needs to be combined with inclusive teaching: “treating students with dignity and respect, communicating confidence in students’ ability to meet high standards, and demonstrating a genuine interest in students’ intellectual and personal growth and success” (Theobald et al., 2020).

“Active learning in itself is not a panacea for STEM equity; rather, to maximize the benefits of active-learning pedagogy, instructors should make a concerted effort to use teaching strategies that are inclusive and encourage equitable participation by all students” (Aguillon et al., 2020).

Women like the connections provided by PBL (Reynolds, 2003)

Methods like Problem-Based Learning can potentially benefit women, because there is room for social aspects of learning like working together in a group, supporting each other, collaborating. “Women expressed rather more trust in the information provided by other students, confirmed greater enjoyment in taking responsibility for their own learning and had more positive views about working with students from another course.” (Reynolds, 2003)

Students working in small groups

Whether groups are chosen by students or assigned by teacher should depend on learning outcome and didactical considerations, not “just” student preferences.

Generally, maybe have a mix of some picked members & rest randomized or assigned, or do use assigned/self-selected groups for different activities. Self-chosen is good for those that get actually chosen and want to be in that group, but what about the others?

Optimal group size for (physics) problem solving is three (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

To work on physics problems in an in-person setting, the optimal number of participants is three (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992). A group of three is large enough to generate a lot of different ideas, but at the same time small enough that every student can contribute. But: if students cannot sit facing each other but are sitting in rows next to each other, it is better to group students in pairs, because that what will happen in groups of threes is that two students form a pair and the third gets excluded.

High-ability groups don’t always perform best (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

Mixed-ability groups do as well as high-ability groups, because they keep better on track whereas high-ability groups tend to make problems too complicated and end up on tangents.

Male students ignore female students’ input to their own detriment (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

In physics, it is common that in groupwork, groups with two female and one male student outperform groups with two male and one female student on problem solving, even when the one female student was “articulate and the highest-ability student in the group” – the male students simply ignored her correct reasoning. Same-gender groups work well, too. (Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992)

When assigning groups, cluster minorities rather than stretching them across as many groups as possible (Stoddard et al., 2020)

Don’t stretch women (and probably other minorities) across as many groups as possible! When there is only one “token woman” in a group, she is perceived as less important by her male peers. She will then participate less in the group, and receive less credit when she does. In groups where there is a majority of women, the behavior of the male participants towards the women changes, and that is what changes how much influence the women get (not homophily or self-assessment), and how well they perform. Even though token women are, over time, perceived as more influential, but only in a general sense, not in task-specific assessments. And “regardless of treatment condition, women’s task expertise is incorporated into group decisions less often than men’s”. “Our findings have implications for team assignments in male-dominated settings and cast significant doubt on the idea that token women can solve influence gaps by “leaning in”” (Stoddard et al., 2020).

(Nice podcast with the author of the study: https://teaforteaching.com/182-gender-and-groups/)

“Women-only exercise groups” sometimes recommended by teachers at LTH

At LTH, Nilsson & Regnell (2016) find that women are looking for environments in which everybody starts out from the same prior knowledge, rather than risking being the only beginner and also a minority in terms of gender: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21215 this is also on programming

Also at LTH, Fuentes et al. (2005) recommend “women-only exercise groups” for beginners in programming: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20936,

Also at LTH, Bränning et al. (2005): https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20941

However, whether that is actually helping without considering the teacher, teaching style, environment, materials, … and making sure all of those are gender-sensitive is not clear (see for example Hazari et al., 2013 and references therein).

Focussed sessions (interventions) can help decrease achievement gaps

Achievement gaps caused by many different reasons can be reduced interventions – focussed teaching sessions with the goal of addressing the cause of the achievement gaps, usually without making that intent explicit. The interventions presented below all reduce the achievement gap by improving the achievement of previously underperforming groups, without negatively affecting other students’ achievement.

Help students see that they belong in the classroom and that adversity is normal, temporary, and surmountable (Cohen et al., 2006; Hammarlund et al., 2022)

Short in-class writing tasks can have large effects. For example, Cohen et al. (2006) showed a reduction of racial achievement gap by 40% through significant improvement of African American students’ grades. In an intervention with the goal “to instill norms that adversity is normal, temporary, and surmountable”, Hammarlund et al. (2022) eliminated a performance gap based on ethnic backgrounds a short in-class writing intervention about challenges students had faced and how they had overcome them.

We are currently working on reproducing the Hammarlund et al. (2022) in Norwegian geosciences.

Help students remember their values (Martens et al., 2006; Cohen et al., 2009; Mijake et al., 2010)

Affirming students’ values – unrelated to subject matter! – closes achievement gaps.

Ranking 11 “characteristics and values” and writing about the personal relevance of their highest-ranked value lets women under stereotype threat perform at levels comparable to men and to women in a no-threat control condition. Self-affirmation does not influence men’s performance (Martens et al., 2006).

Short, structured writing assignments on self-affirming a value reduce the racial achievement gap, especially for initially low-achieving students, over more than two years. “Findings suggest that because initial psychological states and performance determine later outcomes by providing a baseline and initial trajectory for a recursive process, apparently small but early alterations in trajectory can have long-term effects.” (Cohen et al., 2009)

10-15min writing exercise on personally important values, unrelated to subject of course, closes the gender achievement gap over two years. Women who believed that men do better in physics than woman benefitted the most from this intervention (Mijake et al., 2010).

Communication

Global English (Aarup Jensen et al., 2017)

There is no one standard English, and when working with multi-cultural groups, it is helpful to be aware of “global English”: “When working through the shared medium of Global English, it is crucial that all varieties of English be accepted as equal. We all bring into the intercultural encounter linguistic preferences and biases. A Danish student, for instance, is likely to prefer a Dutch, German or Swedish variant of English to that of a Chinese or Ugandan. This is not because Germans necessarily speak better English than the Chinese, but they make mistakes that are similar to those of a Dane, and their message will therefore appear to be more comprehensible.

To favour certain types of English is natural and need not create problems in multicultural teamwork. However, what you need to watch out for is ethnocentrism – jumping to the conclusion that because the German is easier for a Dane to understand, s/he is necessarily ‘better’ at English.”

https://www.en.culture.aau.dk/digitalAssets/324/324074_global-english.pdf

If you are new to the Swedish educational system, be aware of cultural differences (Natalle, 2012)

One place to start to avoid at least some cultural pitfalls might be to read how an American professor teaching in Sweden describes her experiences around “classroom processes such as greeting practices, dress, grading, attendance, gendered language use, and participation” (Natalle, 2012).

It matters to students that teachers make an effort to know their names (Tip: name tents!) (Cooper et al., 2017)

Cooper et al. (2017) show that it matters to students whether teachers make an effort to know students’ names (but not whether the teacher actually does know their name!).

When students think the instructor knows their names, it affects their attitude towards the class since they feel more valued and also more invested.

Students then also behave differently, because they feel more comfortable asking for help and talking to the instructor in general. They also feel like they are doing better in the class and are more confident about succeeding in class.

It also changes how they perceive the course and the instructor: In the course, it helps them build a community with their peers. They also feel that it helps create relationships between them and the instructor, and that the instructor cares about them, and that the chance of getting mentoring or letters of recommendation from the instructor is increased.

Read more about my thoughts on that topic here: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2021/06/21/why-its-important-to-use-students-names-and-how-to-make-it-easy-use-name-tents-after-cooper-et-al-2017/

Sensitive language

Gender-sensitive communication

“Gender-sensitive language is gender equality made manifest through language. Gender equality in language is attained when women and men – and those who do not conform to the binary gender system – are addressed through language as persons of equal value, dignity, integrity and respect.” (EIGE, 2022)

The European Institute of Gender Equality has a great website on the topic that includes lots of helpful information on terms, when and why we need to mention gender, key principles for inclusive language use, practical tools, knowledge tests, and much more:

Preferred gender pronouns

I like the suggestion of inviting students to tell me their name and preferred gender pronouns if they so choose, and I disclose my own preferred pronouns (for example with my zoom name). I do this because I want to help normalize sharing preferred pronouns, so people are addressed the way they prefer, without having to ask for it.

Laura Guertin’s blogpost and the references therein are a good entry point into the topic:

Guertin, L. (2021) “Pronouns in the classroom… to ask, or not to ask, and how to ask”, https://blogs.agu.org/geoedtrek/2021/02/25/pronouns/ (accessed 1.4.2022)

Disability-sensitive communication

The UN Geneva (2021) provides guidelines on disability-inclusive language:

https://www.ungeneva.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/Disability-Inclusive-Language-Guidelines.pdf

However, their advice to “use people-first language” is not valid in all countries. In the UK, apparently “disabled people” is preferred over “people with disabilities” (ACE Disability network, 2022).

Questionable terminology and better alternatives

There is a lot of technical terminology that potentially makes people feel excluded, awkward, or unsafe, that can super easily be exchanged for alternative terminology, which in most cases is equally, if not more, clear. One example is the “plug and socket” terminology for what is sometimes still called “male and female” connectors on cables (great blogpost here: https://cdm.link/2021/07/so-yeah-lets-just-use-plug-and-socket-industry-group-recommends-obvious-change-in-terminology/)

The best overview I could find on inclusive language in STEM (including explanations for why terminology is NOT inclusive, and then providing better alternatives) is this one: https://itconnect.uw.edu/work/inclusive-language-guide/

I wrote a blogpost on the topic: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2022/05/20/choosing-technical-terminology-that-does-not-make-people-feel-excluded-or-uncomfortable/

When and how to address issues of diversity and inclusion in teaching (when it is not the topic of the course)

There are different aspects to consider for when to address issues of diversity and inclusion in a teaching context, when they are not directly relevant to the planned content. The best way to deal with it will depend on context like general (anticipated) climate in the group, if there are people clearly affected by what was (anticipated to be) said, group size, available time, whether one is quick enough to think of a good response or needs more time to prepare, whether a conflict would be escalated, …

One thing to keep in mind is that if you are not reacting directly in a situation, it signals to everybody that you accept it the way it happened. Circling back to it later can be a good strategy, but the longer a statement stands un-challenged, the more it becomes established as acceptable.

Examples of gender and equality sensitive situations in teaching

Wierzbicka & Borell (2018) present three cases of “gender and equality sensitive situations in teaching” experienced by teachers at LTH, so we can reflect on those examples and prepare for similar situations: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21251

At LTH, Bränning et al. (2005) discuss ways to deal with male take-overs: https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20941

Interrupting microaggressions (Thurber & DiAngelo, 2018)

Microaggressions are small, sometimes even unintentional aggressions against members of marginalized groups, that can still have a large impact. But there are ways to deal with them: Check out the brilliant article by Thurber & DiAngelo (2018). “Microaggressions: Intervening in three acts”, Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 27:1, 17-27, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15313204.2017.1417941

How to (not) react when you have committed a microaggression: https://guidetoallyship.com/#how-to-handle-mistakes

Helpful racism interrupters: https://www.instagram.com/p/CCCOlDFDMea/?hl=en

And here is a blogpost I wrote about microaggressions

Purposefully observing gender-relevant situations: “genusobservatörer” (Carstensen, 2006)

One suggestion to work on your own and the class’ gender sensitivity is to use “gender observers” (Carstensen, 2006): two or three students are tasked with observing and providing feedback on interactions in the group, between students as well as students and the teacher. The role of “gender observer” should rotate so that all students get the opportunity to take on that perspective and act in that role.

What kind of resistance to expect when gender becomes a topic of conversation (Carstensen, 2006)

Talking about gender triggers typical responses (Carstensen, 2006):

Falsification: claiming the research on gender is not scientifically sound

Foreclosure: acknowledging that gender might be relevant in the general sense, but is perceived as irrelevant in one’s own life

Dismissal: rejecting gender and research on gender categorically

These responses are also triggered in context of discussions of other inequalities, not just gender. It is helpful to think about how one would react to those types of responses.

“Harassment” is a really tricky (and potentially not helpful) concept (Carstensen, 2016)

“Sexual harassment” was coined as a term to provide visibility to this shared and common experience of many women, and to criticize the “boys will be boys” reaction/excuse. Defining harassment through what is subjectively perceived as harassment was meant to “give women the right to define their experiences of unwanted sexual advances in their own words and to give them positions as subjects.” But this lack of objective measures is not without problems: “firstly, […] the subjective perceptions of the potential victim seem to be of only minor importance when it comes to actual measures and remedies—that is to say, for changing negative gender structures in workplaces; and, secondly, potential victims of harassment tend to interpret the situation in which they are involved as something else. Therefore, the mere making of sexual harassment into a subjective experience probably has little effect on organizational structures.”

Also, sexual harassment often ends up having to fulfill not only the subjective perception, but also meet some rules that were written down to provide examples and guidance for what the term encompasses. This makes it in fact more difficult for sexual harassment to be recognized as such.

Assessment

It matters who gives an exam because it can activate stereotype threats (Marx & Roman, 2002; Marx & Goff, 2005)

Black participants don’t suffer underperformance when tests are given by Black experimenters (but otherwise they do) (Marx & Goff, 2005)

Competent female experimenters (i.e. role models) protect women’s math test performance by influencing women’s self-appraised math ability, which in turn leads to successful performance on a challenging math test (Marx & Roman, 2002)

If you have to ask about demographics, do it after the test so you don’t activate stereotype threat (Danaher & Crandall, 2008)

When you have to ask students for demographics for some reason, do it after the test and not on the cover sheet (in order to not activate stereotype threat before the test). (Danaher & Crandall, 2008)

Multiple-choice questions and gender bias

Multiple choice questions vs constructed response questions (Weaver & Raptis, 2001)

On multiple-choice questions male students perform better than female students, and on constructed response questions female students perform better than male students, but it is not clear why (Weaver & Raptis, 2001).

Negative marking for multiple-choice questions (Funk & Perrone, 2016)

Penalties for wrong answers do not harm female students. “Whereas risk aversion did not affect overall scores (despite affecting answering behavior), ability did. High-ability students performed relatively better with negative marking, and these were more likely to be women.” (Funk & Perrone, 2016).

Women are more conservative and timid test takers than men (Pekkarinen, 2015)

When under competitive pressure, women behave more conservatively and timidly than men (Pekkarinen, 2015).

The teacher

Your own growth-mindset matters (Hammarlund, 2022)

Hammarlund et al. (2022) show that their ecological-belonging intervention ”boosted scores in the classrooms of instructors with a fixed (versus growth-oriented) intelligence mindset. Our results suggest that ecological-belonging interventions are more effective in more threatening classroom contexts”.

Gender bias is everywhere and it is also acting against teachers

Women have to be better than their male peers to be perceived as equal to them in academic hiring decisions (Eaton at al., 2020)

When identical CVs of postdoctoral candidates, differing only in the names, are ranked on competence, hireability, and likeability, the male candidates are perceived as more competent and hirable than the female candidates (with the only difference between the candidates being a male vs female name). There is also a racial bias where Asian and White candidates are perceived as more competent than black candidates, and as more hirable than Black and Latinx candidates. Back and Latinx women (the only difference being, again, the name on the CVs) were perceived as least competent. In terms of likeability, women were rated highest though (Eaton at al., 2020).

Student evaluations of teaching are biased (Heffernan, 2021; but there are ways to use them for good nevertheless! Roxå et al., 2021)

There are a lot of problems with student evaluations of teaching in general, especially when they are used as a tool without reflecting on what they can and cannot be used for. Heffernan (2021) finds them to be sexist, racist, prejudiced and biased.

Here at LTH, course evaluations use a research-based instrument, the Course Experience Questionnaire (CEQ), together with a structured conversation between students, teachers and program responsibles, to use student feedback to improve teaching (Roxå et al., 2021). The student feedback is not used in hiring or promotion decisions, and free text comments are moderated by students that are specifically employed for this job.

Read more about this here: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2022/03/06/using-student-evaluations-of-teaching-to-actually-improve-teaching-based-on-roxa-et-al-2021/

There is a backlash for men violating gender stereotypes (Moss-Racusin et al., 2018)

Gender stereotypes are problematic for men, too. Men are aware that they have to avoid acting in any way that could be interpreted as feminine, that they have to “be a winner”, that they cannot show weakness or emotions, and that they have to be “one of the boys”. This leads to a lot of pressure and emotional stress, and ultimately to mental and physical problems. Backlash for men that don’t adhere to the stereotype can consist of prejudices, which then lead to discrimination and economic consequences. For an organization, hyper-masculine behavior is highly problematic, because one facet of it is to resist changing towards a more equal, caring, and ultimately healthier structure (Moss-Racusin et al., 2018).

There is documented gender bias at LTH

Teachers at LTH have, on average, a “Slight automatic association for Male with Science and Female and with Liberal Arts” (Allanson et al., 2021)

There is a gender bias at LTH staff at all career levels that is not statistically significantly different from results of a huge study in the US (Allanson et al., 2021).

Some teachers at LTH write in ways that suggest that men are superior to women (Berndtsson & Thern, 2012)

An analysis of reports submitted to ”LTHs inspirationskonferenser” showed that three out of 16 texts included metaphors about power dynamics between men and women that suggest that men are superior to women (Berndtsson & Thern, 2012).

From personal experience, I can also report that there is a lot of this type of language around at LTH!

Talking about gender, race, and other prejudices and biases is difficult!

Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism (DiAngelo, 2018)

Many of us grew up privileged but unaware of the privilege. When challenged on our behavior, this challenges how we see ourselves – as good people that don’t harm others. Emotional responses like guilt and anger are therefore common, and they are often expressed by getting into arguments or by silence treatment – both not conductive to constructive dialogue. A really really good book on the topic is “White fragility – Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism” (DiAngelo, 2018).

Sometimes “nothing happens” and still something happens (Husu, 2020)

Once concept that I found really eye-opening when I first heard about it are “non-events”: Sometimes it’s the things that do not happen that are still discriminating against minorities: “silence, exclusion, being ignored or bypassed, reluctant support, lack of validation, invisibility, not receiving credit or being cited, not being listened to and not being invited along”. “Such non-events are challenging for the women concerned to name, make sense of and respond to. As single events, they can often appear rather insignificant and not worthy of attention, but it is the impact of their accumulation in academia, over many years, that is of interest” (Husu, 2020).

“Visibility paradox”: women can be simultaneously highly visible and invisible (Husu, 2020)

“On the one hand, for male colleagues, women academics may be highly visible as women with male behaviours on a continuum of: women being complimented on their looks and clothes in academic and professional settings, to getting sexist comments or being targets of sexual harassment. On the other hand, academic women may remain relatively invisible to their male colleagues and managers as academic colleagues and peers: another form of non-event” (Husu, 2020)

Legal aspects: Defamation lawsuits (Damström, 2020)

Speaking about harassment as a target is difficult because it is stigmatizing, embarrassing, emotionally exhausting. It is also not guaranteed that you will be believed. In some recent cases in Sweden, “to disseminate information about being victim of sexual violence and name your perpetrator, constituted the crime of defamation” (Damström, 2020).

What can you do to support equality?

“Gender mainstreaming” (European Commission, 2000)

Work on equality and related topics is often done in either a grassroot fashion (trying to put out fires locally) or top-down (through policies that are disconnected from individual experience) without broad buy-in, and often by the minorities that are trying to compensate for the disadvantage they experience, which adds another layer of disadvantage for those individuals, as they take on more work and emotional labor. Therefore, “gender mainstreaming” is an important goal: “the systematic integration of equal opportunities for women and men into the organization and its culture and into all programmes, policies and practices; into ways of seeing and doing” (European Commission, 2000)

Women: don’t downplay the effects of gender! (Korvajärvi, 2021)

In a study in Finland, one of the most equal societies in the world, pattern were found of how highly-educated women in male-dominated work communities “do gender”. Often, these women downplay the effects of gender and, despite providing examples of gendered discrimination they have experienced themselves, maintained that gender could not be the cause (Korvajärvi, 2021). This is a mechanism to protect themselves, but it also does not help the conversation.

Men: accept evidence of gender biases in STEM! (Handley et al., 2015)

Men, especially faculty in STEM, are reluctant to accept scientific evidence of gender biases in STEM (Handley et al., 2015). Since they are also the majority, this can hinder changes to the system since the problem needs to be recognized and acknowledged before it can be fixed.

Install institutional strategies for gender equity! (Laursen & Austin, 2020)

There are data-driven strategies to work towards gender equity in the academic system that “fix the system, not the women”. Laursen & Austin (2020) give actionable advice on four main themes that make universities more equitable for everyone (not just women):

Many processes in recruitment, hiring, tenure, and promotion are biased, but there are ways to counteract the biases.

Workplaces themselves need an overhaul to make them more equitable, for example by addressing institutional leadership, improving climate at departments, or making gender issues more visible.

People need to be seen and supported as whole persons if we want to attract diversity into the workplace, for example by supporting dual-career hires, allowing flexibility in work arrangements, or providing adequate accommodation.

While we are still working on the whole system becoming more equable, individual success of people who are already in the system can be supported by providing grants, development programmes, or mentoring and networking

Read more about this here: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2021/06/24/building-gender-equity-in-the-academy-laursen-austin-2020/

Be careful to not write biased letters of references! (Madera et al., 2009)

In letters of recommendation, women are typically described as less able to control their own goals and destiny and more community focused than men. A community focus has negative effects on being hired in academia (Madera et al., 2009).

There is a gender bias “calculator” to check letters of recommendation with: https://www.tomforth.co.uk/genderbias/

References

Aarup Jensen, A., Jæger, K., Krogh, L., & Tange, H. (2017) ” COMMUNICATING IN GLOBAL ENGLISH” https://www.en.culture.aau.dk/digitalAssets/324/324074_global-english.pdf (accessed on 25.5.2022)

ACE Disability network (2022). “The Language of Disability” https://www.acedisability.org.au/information-for-providers/language-disability.php (accessed on 1.4.2022)

Agardh, A., et al. (2020). “Tellus-sexuella trakasserier, trakasserier och kränkande särbehandling vid Lunds universitet.” https://tellus.blogg.lu.se/files/2020/09/Tellus-sexuella-trakasserier-trakasserier-och-krankande-sarbehandling.pdf

Aguillon, S. M., Siegmund, G. F., Petipas, R. H., Drake, A. G., Cotner, S., & Ballen, C. J. (2020). Gender differences in student participation in an active-learning classroom. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 19(2), ar12.

Allanson, J., Johansson, A., Lindström, J., Åström, J. (2021). “Gender in academia – a small experimental study on implicit assumptions”, Project carried out in the CEE course Introduction to teaching and learning in higher education, December 2021, Lund, 2022.

Ballen, C. J., Danielsen, M., Jørgensen, C., Grytnes, J. A., & Cotner, S. (2017). Norway’s gender gap: classroom participation in undergraduate introductory science. Nordic Journal of STEM Education, 1(1), 262-270.

Berndtsson, J. C., Thern, M. (2012). “De Lärdas Pedagogiska Språk” 2012: LTHs pedagogiska inspirationskonferens – Proceedings. https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20841

Beyer, S. (1998). Gender differences in causal attributions by college students of performance on course examinations. Current psychology, 17(4), 346-358.

Brand, S. T., Favazza, A. E. & Dalton, E. M. (2012) Universal Design for Learning: A Blueprint for Success for All Learners, Kappa Delta Pi Record, 48:3, 134-139, DOI: 10.1080/00228958.2012.707506

Bränning, C., Dederichs, A. S., Petersson, A., Åstrand, K. (2005). ”Counterworking Male Takeover during Class Room Activities in Superior Technical Education”, 2005: LTHs pedagogiska inspirationskonferens – Proceedings. https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20941

Carstensen, G. (2006). Könsmedveten pedagogik. Konkreta tips. https://teknat.uu.se/digitalAssets/131/a_131264-f_konsmedvetenpedagogik_090820.pdf

Carstensen, G. (2016). Sexual Harassment Reconsidered: The Forgotten Grey Zone, NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 24:4, 267-280, DOI: 10.1080/08038740.2017.1292314

Cheryan, S, Plaut, VC, Davies, PG, and Steele, CM (2009), Ambient belonging: how stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 97, No. 6, pp. 1045.

Cohen, GL, Garcia, J, Apfel, N, and Master, A (2006), Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention, Science, Vol. 313, No. 5791, pp. 1307-1310.

Cohen, GL, Garcia, J, Purdie-Vaughns, V, Apfel, N, and Brzustoski, P (2009), Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap, Science, Vol. 324, No. 5925, pp. 400-403.

Cooper, K. M., Haney, B., Krieg, A., & Brownell, S. E. (2017). What’s in a name? The importance of students perceiving that an instructor knows their names in a high-enrollment biology classroom. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(1), ar8.

Damström, L. (2020). # MeToo, Men’s Sexual Violence against Women and the Chilling Effect of Defamation Lawsuits: A Feminist Critique of the Swedish Criminal Justice System. Master Thesis-International Human Rights Law Programme.

Danaher, K, and Crandall, CS (2008), Stereotype threat in applied settings re- examined, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 1639-1655.

Dessent, C. E., Dawood, R. A., Jones, L. C., Matharu, A. S., Smith, D. K., & Uleanya, K. O. (2021). Decolonizing the Undergraduate Chemistry Curriculum: An Account of How to Start. Journal of Chemical Education.

DiAngelo, R. (2018). White fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Beacon Press.

Druckman, J. N. (2021). Bias in Higher Education Disability Accommodation Services. Available at SSRN 3823973. https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/working-papers/2021/wp-21-34.pdf

Eaton, A. A., Saunders, J. F., Jacobson, R. K., & West, K. (2020). How gender and race stereotypes impact the advancement of scholars in STEM: Professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex Roles, 82(3), 127-141.

EIGE (European Institute for Gender Equality), 2022

https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-sensitive-communication/first-steps-towards-more-inclusive-language/terms-you-need-know (accessed on 1.4.2022)

Espinoza, P., Arêas da Luz Fontes, A. B., & Arms-Chavez, C. J. (2014). Attributional gender bias: Teachers’ ability and effort explanations for students’ math performance. Social Psychology of Education, 17(1), 105-126. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11218-013-9226-6

European Commission (2000). Science Policies in the European Union: Promoting Excellence through Mainstreaming Gender Equality. A Report from the ETAN Expert Group on Women and Science.

Fuentes, A., Andersson, J., Johansson, J., Nilsson, P. (2005). “Gender and Programming: A Case Study”, 2005: LTHs pedagogiska inspirationskonferens – Proceedings, https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/20936

Funk, P., & Perrone, H. (2016). Gender differences in academic performance: The role of negative marking in multiple-choice exams.

Guertin, L. (2021) “Pronouns in the classroom… to ask, or not to ask, and how to ask”, https://blogs.agu.org/geoedtrek/2021/02/25/pronouns/ (accessed 1.4.2022)

Hammarlund, S. P., Scott, C., Binning, K. R., & Cotner, S. (2021). Context Matters: How an Ecological-Belonging Intervention Can Reduce Inequities in STEM. BioScience.

Handley, I. M., Brown, E. R., Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Smith, J. L. (2015). Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(43), 13201-13206.

Hazari, Z., Potvin, G., Lock, R. M., Lung, F., Sonnert, G., & Sadler, P. M. (2013). Factors that affect the physical science career interest of female students: Testing five common hypotheses. Physical Review Special Topics-Physics Education Research, 9(2), 020115.

Hedvall, P.-O., Mattsson, P. (2021). “Introducing Norm Creative Perspectives in Engineering and Design Educations” LTHs 11:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 9. december 2021, https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/23847

Heffernan, T. (2021). Sexism, racism, prejudice, and bias: a literature review and synthesis of research surrounding student evaluations of courses and teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1-11.

Heller, P., & Hollabaugh, M. (1992). Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups. American journal of Physics, 60(7), 637-644.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. & Norenzayan, A. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 466, 29 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a

Husu, L. (2020). ”What does not happen: interrogating a tool for building a gender-sensitive university” In: Eileen Drew and Siobhán Canavan (ed.), The Gender-Sensitive University. A Contradiction of terms? (pp. 166-176). London and New York: Routledge https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003001348

Korvajärvi, P. (2021). Doing/Undoing Gender in Research and Innovation–Practicing Downplaying and Doubt. Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 5(2), 27.

Laursen, S., & Austin, A. E. (2020). Building gender equity in the academy: Institutional strategies for change. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Leaper, C., & Starr, C. R. (2019). Helping and hindering undergraduate women’s STEM motivation: Experiences with STEM encouragement, STEM-related gender bias, and sexual harassment. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(2), 165-183.

Lorenzo, M., Crouch, C. H., & Mazur, E. (2006). Reducing the gender gap in the physics classroom. American Journal of Physics, 74(2), 118-122. https://aapt.scitation.org/doi/full/10.1119/1.2162549

MacLaren, N. G., Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Sayama, H., Mumford, M. D., Connelly, S., … & Ruark, G. A. (2020). Testing the babble hypothesis: Speaking time predicts leader emergence in small groups. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(5), 101409.

Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., & Martin, R. C. (2009). Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: agentic and communal differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1591.

Martens, A, Johns, M, Greenberg, J, and Schimel, J (2006), Combating stereotype threat: The effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 236-243.

Marx, DM, and Goff, PA (2005), Clearing the air: The effect of experimenter race on target’s test performance and subjective experience, British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 645-657.

Marx, DM, and Roman, JS (2002), Female role models: Protecting women’s math test performance, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 28, No. 9, pp. 1183-1193.

McIntyre, RB, Paulson, RM, and Lord, CG (2003), Alleviating women’s mathematics stereotype threat through salience of group achievements, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 83-90.

Miyake, A, et al. (2010), Reducing the gender achievement gap in college science: A classroom study of values affirmation, Science, Vol. 330, No. 6008, pp. 1234-1237. https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.1195996

Natalle, E. J. (2012). An American Professor’s Perspective on the Dialectics of Teaching Interpersonal Communication in the Swedish Classroom. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 24(2), 168-179.

Nilsson, S., Regnell, B. (2016). ”Utan män vågar kvinnor prova – lärdomar avgenusseparerad programmeringsundervisning.” LTHs 9:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 15 december 2016, https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21215

Pekkarinen, T. (2015). Gender differences in behaviour under competitive pressure: Evidence on omission patterns in university entrance examinations. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 115, 94-110.

Phoenix, A., & Pattynama, P. (2006). Intersectionality. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(3), 187-192. Chicago

Reynolds, F. (2003). Initial experiences of interprofessional problem-based learning: a comparison of male and female students’ views. Journal of interprofessional care, 17(1), 35-44.

Rydeman, B., Eftring, H, Hedvall, P.-O. (2018). “How can we make teaching more inclusive?” LTHs 10:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 6. december 2018

https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21243

Roxå, T., Ahmad, A., Barrington, J., Van Maaren, J., & Cassidy, R. (2021). Reconceptualizing student ratings of teaching to support quality discourse on student learning: a systems perspective. Higher Education, 83(1), 35-55.

Salmonsson, L. (2020). #Akademiuppropet: Social media as a tool for shaping a counter-public space in Swedish academia. In The Routledge Handbook of the Politics of the #MeToo Movement (pp. 439-449). Routledge.

Schnaas, U. (2011). Könsmedveten forskarhandledning: teoretiska utgångspunkter och praktiska erfarenheter.

Smith, T., Brumskill, R., Johnson, A., & Zimmer, T. (2018). The impact of teacher language on students’ mindsets and statistics performance. Social Psychology of Education, 21(4), 775-786.

Soneson, C., & Torstensson, A. (2013). Manliga och kvinnliga teknologers självbilder och deras stereotypbilder av teknologer. Högre utbildning, 3(1), 3-14.

Stadler, H., Duit, R., and Benke, G., “Do boys and girls understand physics differently?,” Phys. Educ.0031-9120 35(6), 417–422 (2000).

Stoddard, Olga B.; Karpowitz, Christopher F.; Preece, Jessica (2020) Strength in Numbers: Field Experiment in Gender, Influence, and Group Dynamics, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 13741, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn

Steele, C. M. (2011). Whistling Vivaldi: How stereotypes affect us and what we can do. WW Norton & Company.

Taylor, J. “Sexist bias in physics textbooks,” Phys. Educ.0031-912014(5), 277–280 (1979).

Theobald, E. J., Hill, M. J., Tran, E., Agrawal, S., Arroyo, E. N., Behling, S., … & Freeman, S. (2020). Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(12), 6476-6483.

Thurber, A., & DiAngelo, R. (2018). “Microaggressions: Intervening in three acts”, Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 27:1, 17-27, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15313204.2017.1417941

Traxler, A. L., Cid, X. C., Blue, J., & Barthelemy, R. (2016). Enriching gender in physics education research: A binary past and a complex future. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(2), 020114.

UN Geneva (2021). DISABILITY-INCLUSIVE LANGUAGE GUIDELINES https://www.ungeneva.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/Disability-Inclusive-Language-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 1.4.2022)

Weaver, A. J., & Raptis, H. (2001). Gender differences in introductory atmospheric and oceanic science exams: multiple choice versus constructed response questions. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 10(2), 115-126.

Weisgram, E. S., & Bigler, R. S. (2007). Effects of learning about gender discrimination on adolescent girls’ attitudes toward and interest in science. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(3), 262-269.

Wierzbicka, A., Borell, J. (2018). “Gender and equality sensitive situations in teaching –can we detect and manage them as they happen?” LTHs 10:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 6. december 2018, https://journals.lub.lu.se/pige/article/view/21251

Yeager, DS, and Dweck, CS (2012), Mindsets that promote resilience: when students believe that personal characteristics can be developed, Educational Psychologist, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 302-314.

Currently reading Månefjord et al. (2025) on "Mind the Gender Gap: Implicit bias in STEM education" - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] They need to publish twice as much as men to be seen as equally competent, and the list goes on (I have compiled a lot of literature here, including even an earlier version of this article!). But since a lot of the research mentioned […]