My awesome colleague Marisa ran another workshop on Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in which I was lucky enough to assist. For the last workshop for people who are planning to use PBL in their teaching, we used the solar eclipse to build a case around. Since this time we weren’t as lucky to have a solar eclipse happening on our second workshop day again, we were in need of a new case. We wanted something that was interesting and challenging enough to our audience of engineers to realize that PBL is a method that can definitely be used for hard science and engineering stuff, too, and that was obscure enough that none of the participants would know all the answers right away, but that on the other hand was solvable with only about an hour of individual research in step 6 between the first and second workshop day. So we were pretty much looking for a magic unicorn.

Enter the oceanography case!

Paul: People always say that Arctic melting is a positive feedback loop. But I don’t think that’s true, that’s all part of the big climate conspiracy! When the ice melts, this decreases the salinity of the sea ice. If there is less salt in the water, though, the ice melts less fast. This means that the process stabilizes itself!

Marie: Come on, Paul, don’t believe everything people tell you! As a scientist you should really be less gullible. The melting of the Arctic is influenced by so many other processes, for example the different albedos of ice and open water. That must be at least as important as the salinity!

Now Paul starts looking for scientific proof for his theory. Marie starts researching as well, she tries to find something Paul can observe himself so her argument doesn’t rely on papers Paul might not trust.

Even more so than in the previous PBL workshop, it was absolutely fascinating how the discussion evolved. Also, this time people were talking about my favorite topic and it was super interesting to see what a crowd of PhD students and PostDocs in engineering knew – and didn’t know – about the climate system.

Steps 1-4 went uneventfully, as described in this post. In step 5, we ended up with four questions that the participants wanted to do research on during step 6, namely

- How does the albedo influence melting of Arctic sea ice?

- How is the salinity of Arctic sea water influenced by the melting of Arctic sea ice?

- How does the salinity of the water surrounding the ice influence the ice’s melting?

- How does atmospheric CO2 influence Arctic melting?

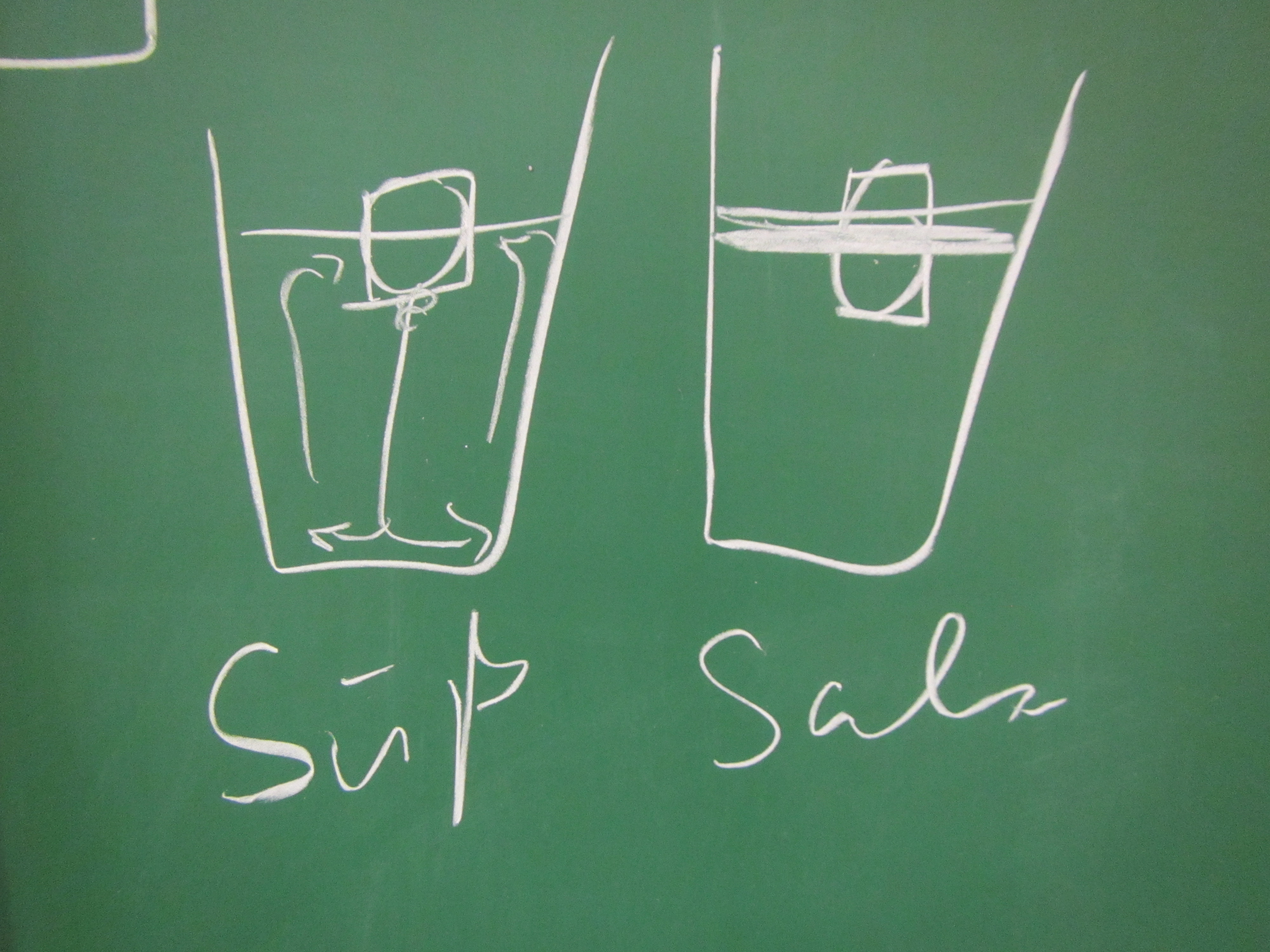

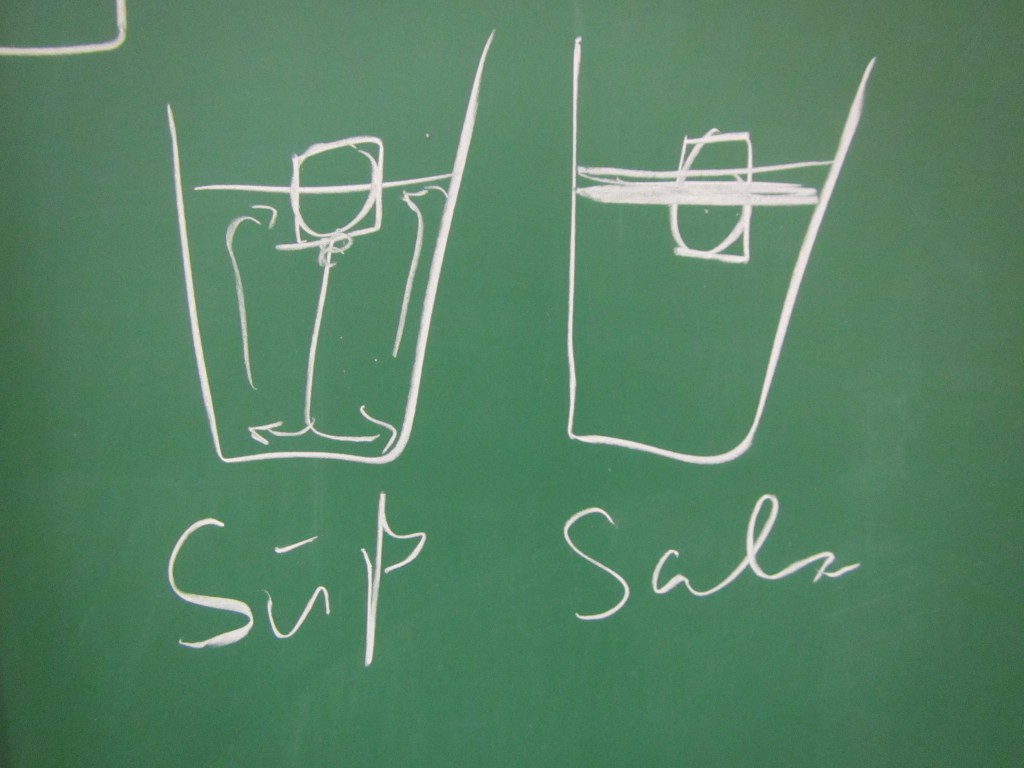

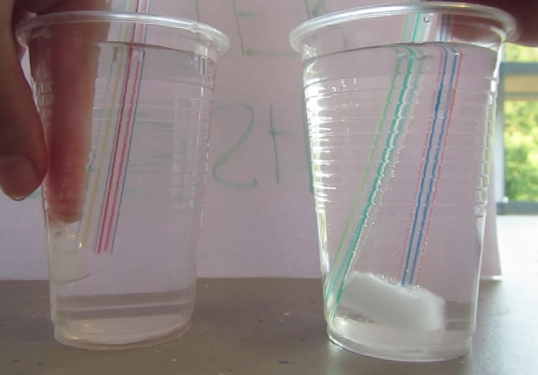

Faithful readers of my blog will have recognized from the case already where the whole PBL session was heading: I wanted them to do my favorite experiment! Just by doing the experiment they could have shown Paul that more salt in sea water doesn’t mean that ice floating in it will melt faster. Luckily they were all good sports and came up with more research questions than just that one, but after discussing their answers to their research questions, we obviously had to do the experiment.

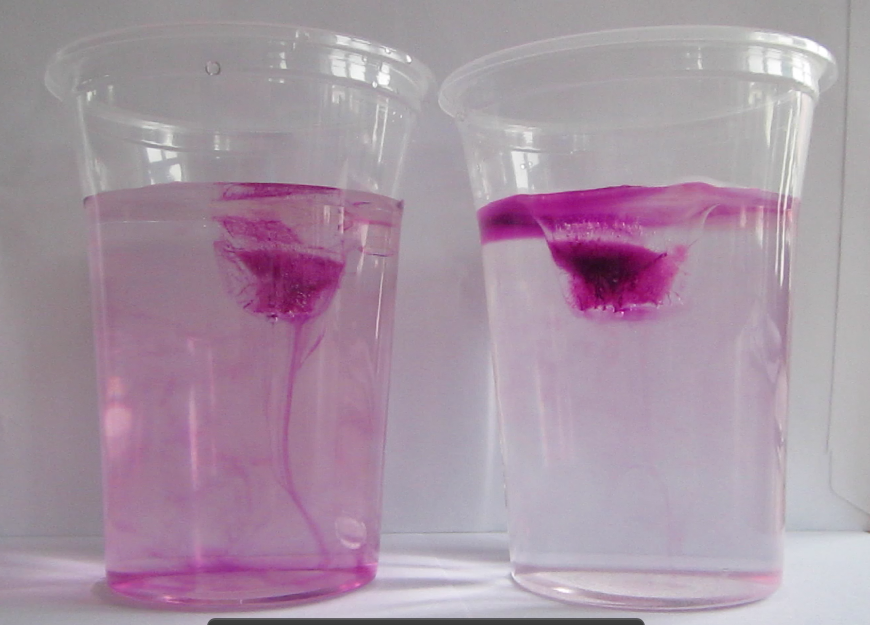

Marisa uses food dye as a tracer for melt water

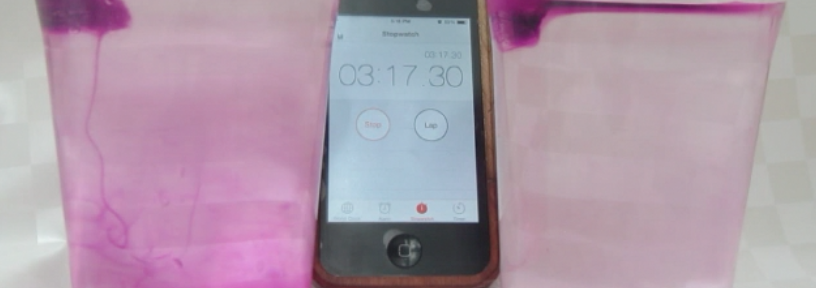

As always, participants did the experiment in groups of 2 or 3. My ice cubes had suffered quite a bit during the day, so the experiment was quite quick. Usually I bring ice cubes in a huge thermos, but this time a) that thermos was at work and my ice cubes were at home on the day of, and b) I only needed so few ice cubes that I thought a thermo mug would do fine. Yeah. Suffice to say, next time I’ll use the thermos again.

And what would happen if we stirred?

In the previous PBL session on this case, there had been quite a long discussion about temperature gradients and stirring, so obviously we had to conclude the experimental part by stirring.

So that was that. How did PBL work for an oceanography case? I really loved it. The first session was really exhausting (as all first PBL sessions are, at least in my limited experience). There were a lot of discussions that went fairly deep into the topic of climate change, and also a broad range of topics related to the melting Arctic was covered. I was actually pretty surprised how far people went into formulating models and how much they knew about different aspects, yet how difficult it was to put everything together. When writing the case, I had expected a lot less of an in-depth discussion of the issue, especially since none of the participants had an explicit ocean/climate background. So really positive surprise here how well it went!

The second session, where everybody brought their results together was great fun, and not only for me (or at least that’s what I think). The goal of our workshop was to have instructors, who will likely use PBL in their own teaching soon, experience the method in a student’s role. Therefore we couldn’t solve all the burning questions of ocean and climate during that second session and had to focus on reflection and the how-tos of the PBL method. But I would definitely use this (or a slightly modified) case in oceanography teaching! And I would also use this case for the same purpose again, although then I would probably make it a little bit more confined in order to leave more time for the meta-aspects of the workshop.

Thanks, Marisa, for another great workshop, I always learn SO MUCH from watching you lead discussions! :-)