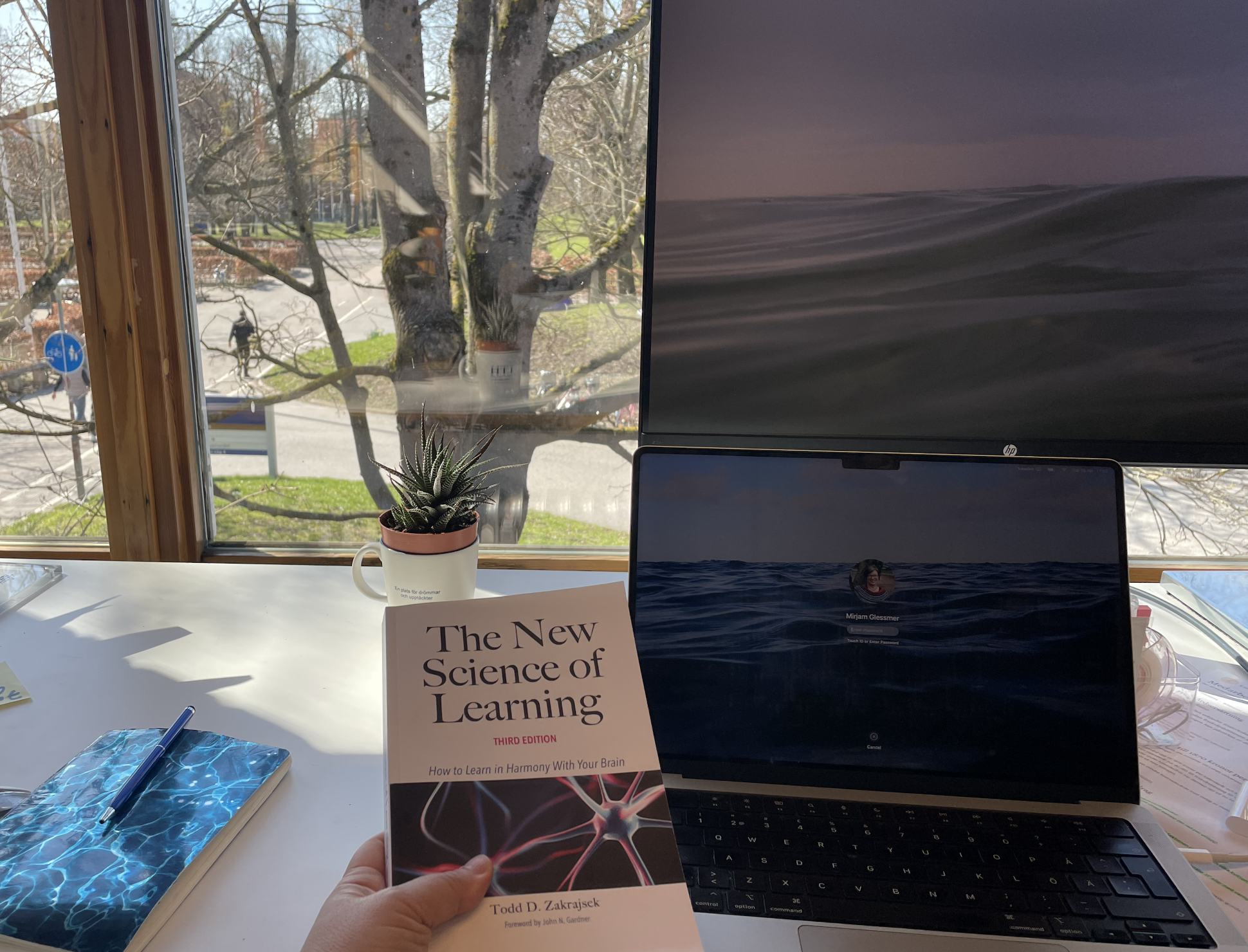

Currently reading Bjork & Bjork (2011) on “Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning”

This is one of these texts that I wish I had known earlier: to give to students to help them understand their learning, but also to teachers as a super easy introduction to how to think about difficulties in learning: “Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance […]