A bit more reflection on cartesian divers.

Category Archives: pondering

Oceanographic concepts and language (part 3)

What level of proficiency do you need to communicate about science?

This post is not strictly about oceanography, but I started thinking about it in the context of a class I taught recently, where I was teaching in a foreign language to me and most of the students.

After one of the classes, a student came to me to thank me that had I continued explaining concepts, even though some of the (native speaker) students thought that that was ridiculous and everybody should know what certain terms meant (posted about here).

And one thing this student and I noted when discussing in a language that was foreign to both of us was that even though our grammar might be not perfect and our vocabulary not as large as that of native speakers, we had a sensitivity for other speakers that many of the native speakers lacked. For example, we discovered that it comes natural to us to speak about “football” to speakers of British English, when we would say “soccer” to speakers of American English. Or that we are aware that trousers and pants might or might not mean the same thing, depending on who you are talking to. And I remember distinctly how on a British ship, sitting at a table with American scientists, I explained that when the stewart asked if we wanted “pudding” we could well end up getting cake, because in the context then what he meant was “dessert”.

When you are a non-native speaker, you get used to listening very carefully in order to understand what is going on around you. In my first months in Norway, for example, I happily watched Swedish TV and would understand as much there as on Norwegian TV. I would recognize words, grammar rules that had been discussed in language class, even phrases. Yet many of my Norwegian friends say they find it hard to understand Swedish. But on the other hand I remember that I found it much easier to communicate in English when in Vienna than to adapt to their German dialect.

Sports-analogies are another example that is typically very language-dependent. I know by now what “pitching an idea” means, but not because I know pitching from a sports context, but because I have heard that phrase used often enough so it stuck. Same for this teaching assistant who helped with my class who I overheard shouting “mud pit!” when he wanted students to remember something about molecular diffusion (or heat?) – the picture I made up in my head is that of players huddling together in a muddy playing field, but I still don’t know what exactly he was referring to (and I’m sure neither do half of the students of that class).

Now, I am not saying that native speakers of any language are necessarily unaware of those peculiarities. But what I am saying is this: If you are a native speaker, and you are communicating with non-native speakers, try to be aware of how you are communicating your ideas, and be sensitive to whether you are understood. And listen carefully to what your students are saying and don’t just assume that non-native speakers can’t possibly have anything interesting to say. And if you are the teacher who taught the class before I taught the class with the student mentioned above, and you told them that their English was not good enough because they didn’t speak (note: not because they didn’t understand, but because they didn’t speak!) your dialect: Learn their language, or any kind of foreign-to-you language, and then we can talk again.

—

And on this slightly rant-y note, I’ll leave you for now. I will be back in the new year on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. I have tons of ideas for more posts (you have no idea how many experiments my family will have to endure over the next couple of days! And I have about 30 hands-on experiment posts in various draft stages written already), and if you end up desperately waiting for new content here, how about you try some of my (or other) experiments and let me know how it went? Have fun playing!

Oceanographic concepts and language (part 2)

How to make lectures in a foreign language less scary for the students.

The class that I have until recently taught in Bergen, GEOF130, is taken by students in oceanography and meteorology in the second year of their Bachelor at the university. It is the first course they take at the Geophysical Institute – their first year is spent entirely at other institutes. The Bachelor is taught in Norwegian – with the exception of GEOF130. This course is taught in English, because it also serves the Nordic Master, which is taught in English, and that brings in many students who don’t speak Norwegian.

While I am glad the course had to be held in Norwegian (I would definitely not have had the time to prepare 4 hours of lectures per week for a whole semester in Norwegian!), many of the students were not happy. They typically understand everything you say just fine, but there is a huge barrier when it comes to speaking in front of their peers in a foreign language.

The easiest way to cope with the shyness I found is to speak to them in my less-than-perfect Norwegian. Seeing the teacher make funny mistakes in a foreign language makes it a lot easier for them to dare making mistakes in another foreign language.

Yet students often choose to write the exam in Norwegian (and yes – I have to pose the questions in English, Nynorsk and Bokmål!). Which often leads to problems, since all of the lectures and all of the reading materials were in English, so the students don’t actually know any of the technical terms in Norwegian and often end up inventing them or, worse, mixing them up with similar sounding but not otherwise related Norwegian terms.

So the next thing to do is to always try and be aware of which terms they are likely to know and which are technical terms. This is not always easy and depends a lot on what their native language is (see this post). One thing I did early on when I started teaching was to create a small dictionary of oceanographic terms in English, Norwegian and German. Anyone out there who wants to help edit that dictionary? And everybody, please feel free to share if you think this might be useful to someone else!

Student cruises (part 5 of many, or – thank you to a great mentor)

The first student cruise I ever taught while being taught by one of the greatest teachers myself.

As you might have noticed from the last four or so blog posts, I really enjoy teaching student cruises and I think they are a super important part of the oceanography education.

So let me tell you about the first student cruise I taught. I was lucky enough to co-teach it with one of the most experienced and knowledgeable oceanographers out there, who was excited about sharing with me all there is to know about cruise planning, cruise leading, teaching at sea and many other topics.

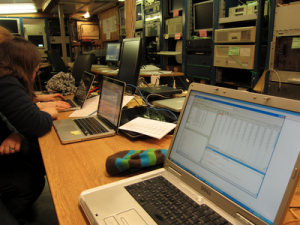

Me and Anne on watch during that student cruise. Picture courtesy of Angus Munro.

From the first day of the first cruise onward, my ideas and contributions were welcomed, and I got to heavily influence the scientific program of the cruise. On the second day of the first cruise, I was told to just walk up to the captain and tell him if I wanted to change the course and go measure somewhere else than planned.

On the bridge, discussing the scientific plan for the next day. Picture courtesy of Angus Munro.

The cruise ended up being great learning experiences for me. For the first time, I got to decide how to allocate ship time to best investigate the question that I thought was most interesting, a topic that I had never had (the chance) to deal with previously.

Getting the small boat ready to recover a mooring. Photo courtesy of Angus Munro.

At the same time, I had the opportunity to learn from – and work with – the best. One of the practical highlights: A mooring release had not been working reliably in the past, but it was the one that we had with us on this cruise. So what to do?

Recovering a mooring. Photo courtesy of Angus Munro.

Easy! Just tie a rope from the mooring to a tree! (Ok, so maybe this isn’t generally helpful, but if you are in Lokksund, this is genius)

And then I got to spend a lot of my time on watch (and a lot of my time off watch) discussing what we were seeing in the new data, what we could learn from that, where we should go next to prove or disprove our new theories.

And I got to watch a great teacher interact with his students (other than me). I saw how he challenged, how he encouraged, how he helped, how he guided, how he inspired.

Bringing the mooring back on deck. Photo courtesy of Angus Munro.

Thank you so much, Tor, for being the role model you are and for having given me all of this, which I have since been striving to give to my own students.

—

All photos in this post were taken by Angus Munro (thanks!) on the 2012 GEOF332 student cruise.

Oceanographic concepts and language (part 1)

About teaching in a language that is a foreign language for both your students and yourself.

Most of my teaching so far has happened in English to mainly non-native English speakers with the occasional native speaker thrown in. One thing that I realized recently was that concepts that are definitely not common knowledge at home in Germany and that are described by technical terms in German, are absolute household terms in other language.

Let’s for example think about density.

In German, or Norwegian for that matter, “Dichte” or “tetthet” is not a concept that is used in everyday language very much, and that therefore needs to be explained in introductions to oceanography, and that typically is rather difficult to understand for the students. I usually introduce density both by talking about mass per volume, and then by showing experiments to visualize what differences in density can look like, for example by showing that soda cans with the exact same volume can still sink or swim depending on what’s inside.

In English however, people have an intuitive understanding of what density is – a measure of compactness. A densely populated area is an area where many people live close together. If a lecture is very dense, there is a lot of content for the amount of time you attend. A low-density floppy disk will not be able to contain as much information as a high-density one. So having this background, not a lot of transfer is needed to be able to talk about the density of water.

I am usually pretty aware that I am teaching in a language that is foreign to both the students and to me, and I try to compensate for that by explaining what I perceive as technical terms. But recently I had a native English speaker in one of my classes, and that person got really upset because I spent so much time on what that person thought was trivial. So I guess language awareness needs to go both ways – not only being aware of what kind of vocabulary students of certain nationalities probably won’t be familiar with, but also being aware of the vocabulary that I learned as technical terms and that are not perceived as technical terms by students of other nationalities.

Dear readers, have you come across this? What other terms can you think of that we should be aware of?

Dangers of blogging, or ice cubes melting in fresh water and salt water

When students have read blog posts of mine before doing experiments in class, it takes away a lot of the exploration.

Since I was planning to blog about the CMM31 course, I had told students that I often blogged about my teaching and asked for their consent to share their images and details from our course. So when I was recently trying to do my usual melting of ice cubes in fresh water and salt water experiment (that I dedicated a whole series on, details below this post), the unavoidable happened. I asked students what they thought – which one would melt faster, the ice cube in fresh water or in salt water. And not one, but two out of four student groups said that the ice cube in fresh water would melt faster.

Student groups conducting the experiment.

Since I couldn’t really ignore their answers, I asked what made them think that. And one of the students came out with the complete explanation, while another one said “because I read your blog”! Luckily the first student with the complete answer talked so quickly that none of the other – unprepared – students had a chance to understand what was going on, so we could run the experiment without her having given everything away. But I guess what I should learn from this is that I have taken enough pictures of students doing this particular experiment so that I can stop alerting them to the fact that they can oftentimes prepare for my lectures by reading up on what my favorite experiments are. But on the upside – how awesome is it that some of the students are motivated enough to dig through all my blog posts and to even read them carefully?

—

For posts on this experiment have a look a post 1 and 2 showing different variation of the experiment, post 3 discussing different didactical approaches and post 4 giving different contexts to use the experiment in.