How can we make sure students actually prepare for the next session?

This post is a work-in-progress – I am working on flipping my first ever class, and this is a collection of my thoughts on the matter which I thought might be interesting to others, too. But I will definitely come back to the topic later once I have more experiences! But let’s get started:

What is a flipped classroom?

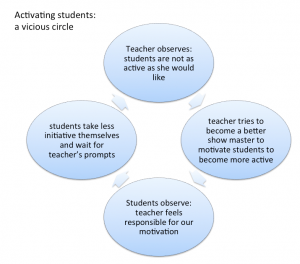

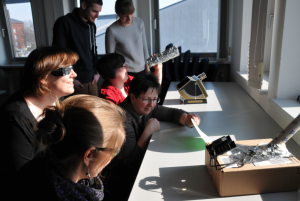

If you are following discussions in higher education, you’ve certainly come across the idea of a “flipped classroom”. What it means in a nutshell is that anything that takes a lot of studying and practicing, but isn’t particularly hard, is moved out of the classroom, so that class time can be used on difficult tasks where students need the instructor’s help. So instead of gathering for content transfer, people gather for things you need to gather for: interactions and discussions.

Why flip your class?

There are many good reasons for flipping your class. In no particular order:

- face-to-face class time is typically limited to 2 to 4 hours per week, so in order to make the best use of it, students should make the most of having an expert present

- most parts of a typical lecture are basically the same as listening to any random person read from a script on a topic. Yes, of course the typical lecturer comments spontaneously on occasion, but compared to “reading time”, those are very short moments, few and far between

- the difference between passively listening to a lecture and passively listen to a video of a lecture is not very large (provided the video has good quality)

- “learning facts” is not really difficult. Making sense is. So this is where the instructor should be supporting the students (for example by giving them the opportunity to discuss during a lecture)

How do you flip your class?

So now everybody is talking about flipping their classes. But how do you actually do it?

We are currently working on the first course to be completely flipped, and here are some concerns we have and some ideas I’ve either heard of somewhere or had myself. I’ll let you know how well they worked after we’ve actually tried…

- How do we make sure students come to class prepared?

This seems to be the biggest worry, which I completely understand. Interestingly, everybody who has tried flipping their class says that it is actually not an issue: Students do realize that if they are not prepared, they won’t gain anything from coming to class. So they come prepared.

But of course there are strategies that can be implemented in order to feel more secure in the beginning:

– Make sure every student gets the opportunity to ask their questions on the topic so students recognize the value of using that time for their own progression.

– Peer pressure. If students work in fixed groups throughout the whole course, group dynamics will tend to make sure everybody pulls their weight.

– Implement a control system: Make pre-class tests grade-relevant or award bonus points.

- How do I decide which materials the students should be studying in preparation for my class?

I really like this question, because I’ve never been asked this for a regular lecture! Even though, of course, this question should always be asked. I think, the answer in this case is fairly easy. You know what kind of activity you will want to do during the class. Have students discuss a certain problem? Then they will have read about that problem beforehand. Apply a method to a new type of problem? Then they should have practiced applying that method to the “regular” type of problem beforehand. Talk about a new topic in a foreign language? Then they need to study the relevant technical terms before coming to class.

Basically, we need to figure out what we want students to be able to do once they are in class, and from there we can go to what information they need in order to do it, and provide that information (see my post on constructive alignment).

- But what if I don’t want videos of my face floating about the internet?

While videos seem to be the preferred medium for content-delivery outside of a flipped classroom, this does not mean that your face has to be visible. You could use screen casts, where you show your slides and add your voice, or you could use other people’s videos which you edit together or ensemble to a playlist, or you could use podcasts or written materials instead of videos. Or you could put your videos on a protected learning management system, but of course then there is no guarantee then that the materials won’t end up on the open internet eventually.

And this is where I am currently at when it comes to flipping a class. I’ll get back to you once we’ve actually tried!

P.S.: Here is a very interesting blog post by Ryan Kilcullen, who discusses a flipped class from a student’s perspective. Make sure to also read the great comments on that post!