Weird things happening when ice cubes melt.

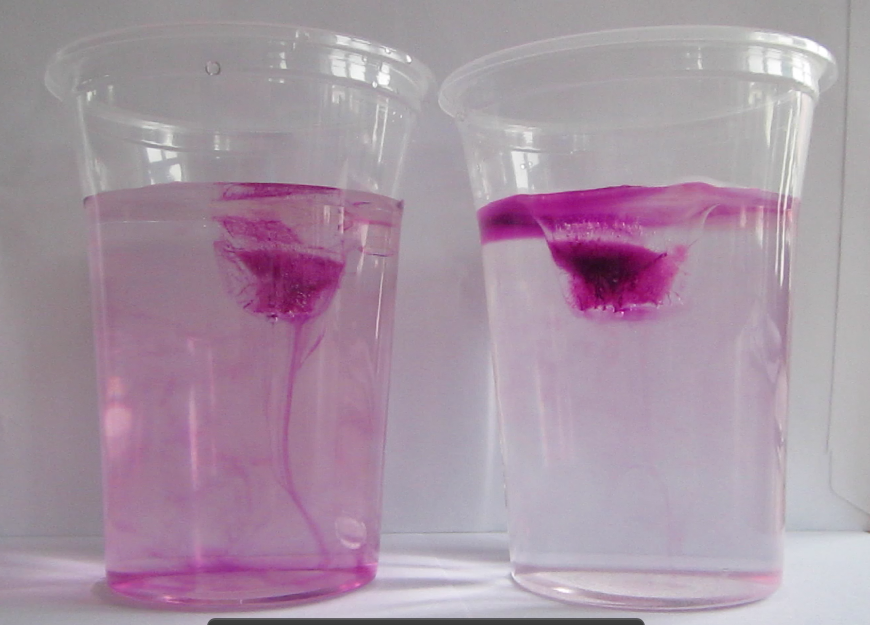

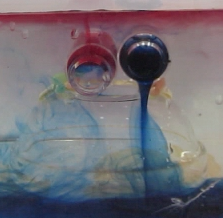

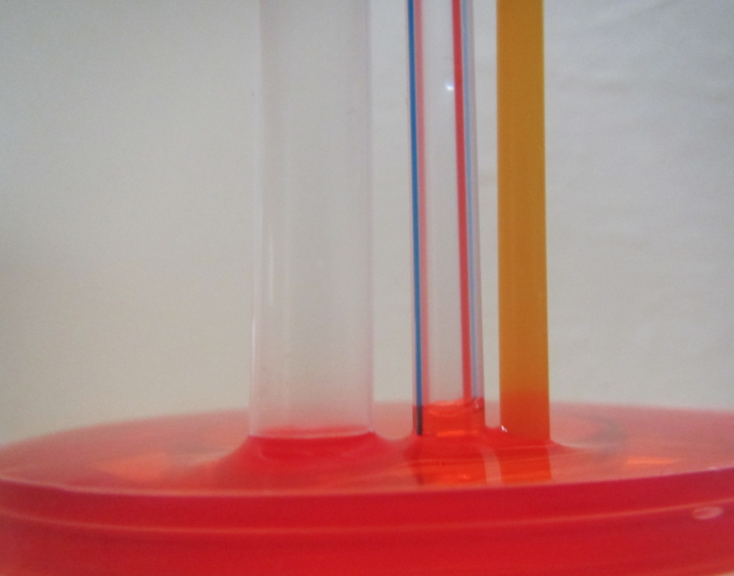

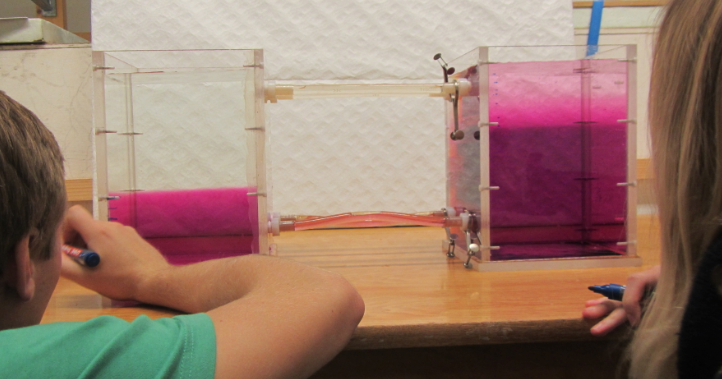

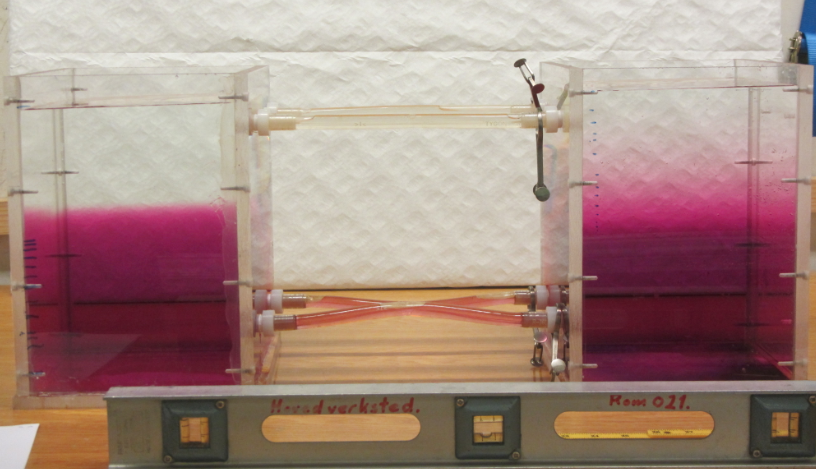

Remember I said that there were weird and wonderful things going on when I last ran the melting ice cubes in salt and fresh water experiment? It is really difficult to see in the picture below (sorry!) but you can probably spot the ice cube floating at the surface and the melt water sinking down, inducing some turbulence? And then there is a small ice bit a bit to the right of the center of the picture. And that ice bit is floating upwards.

Dyed ice cube floating at the surface, and small ice bits floating up

Watch the melting ice cubes video below to see all the thing in action, it is visible really well as soon as the picture is moving:

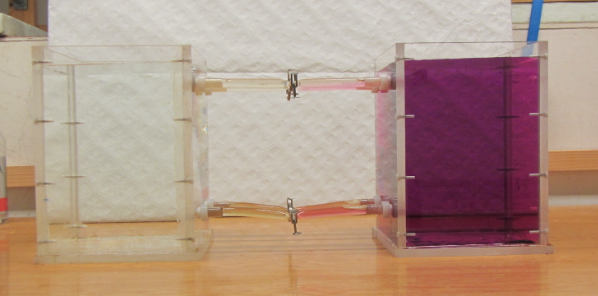

So what is going on there? I think the solution to this riddle lies in me forcing ice to freeze even though it contains more salt (or in this case, red food dye) than it is happy with. Remember how dyed ice cubes look?

Ice cubes frozen from colored water

So basically there is dye trapped in the middle of the cube, because cooling is happening from all sides, hence ice is starting to form from all sides, pushing the dye to the center of the ice cube. In the ocean, cooling would of course only happen from above, so salt is being rejected as brine.

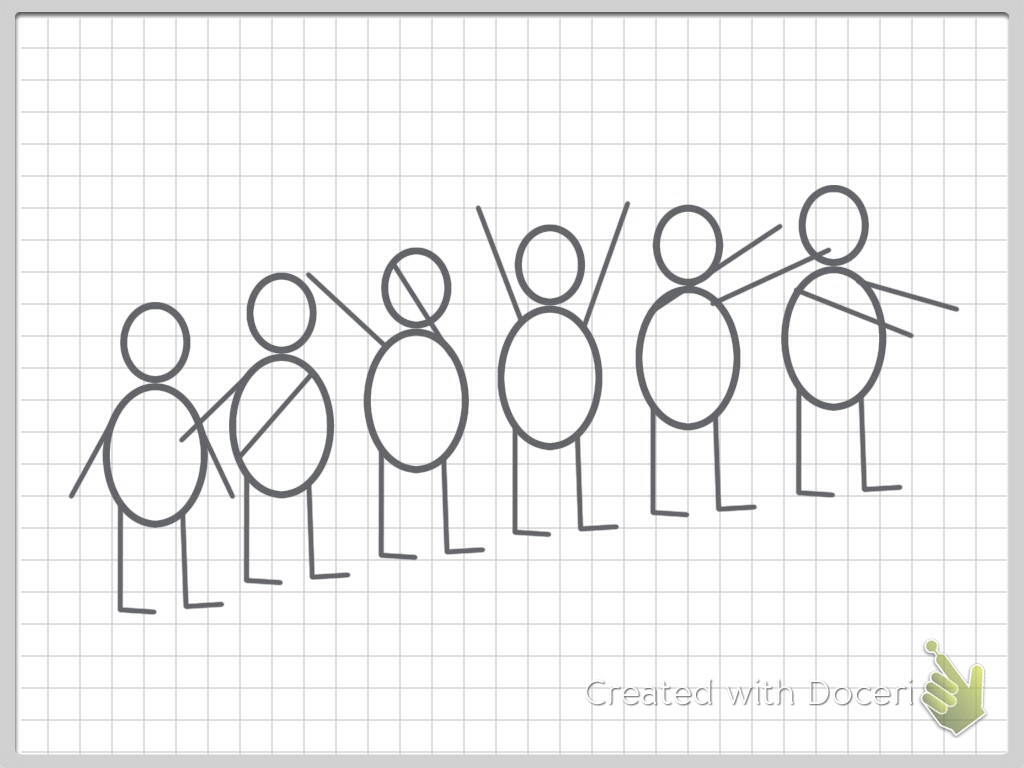

Anyway, since I wanted to dye the ice cubes to make things more visible for this blog, I am adding a dissolved substance to the water that would usually not be there. Hence I am making the ice slightly denser than it would otherwise be. So when small ice bits chip away from the main cube (which still contains large parts of pure fresh water ice from the sides of the cube where, during the freezing, the dye could still be rejected; and which therefore still floats), they are denser than the water and sink. But as they melt, the dye washed out, and eventually the remaining ice is fresh, hence less dense, enough to float up again.

The whole thing looks pretty fascinating.

What do you think, is that the correct explanation? Or can you come up with a better one? Let me know!

P.S.: Everybody I showed this video to was fascinated by how the little piece of ice is floating up. But what I find a lot more fascinating is how it came to be at the bottom of the beaker in the first place! After all, ice is supposed to float on water (or drift up again if pulled down and then released) but how did it get down there???