Now published: Glessmer, Curtis, & Thoni (2025) on “Two years of the initiative Teaching for Sustainability at Lund University – understanding challenges and exploring opportunities”

Together with my colleagues Steven Curtis and Terese Thoni, I ran a workshop at the Lund University Teaching and Learning conference 2024 — and now the proceedings have been published!

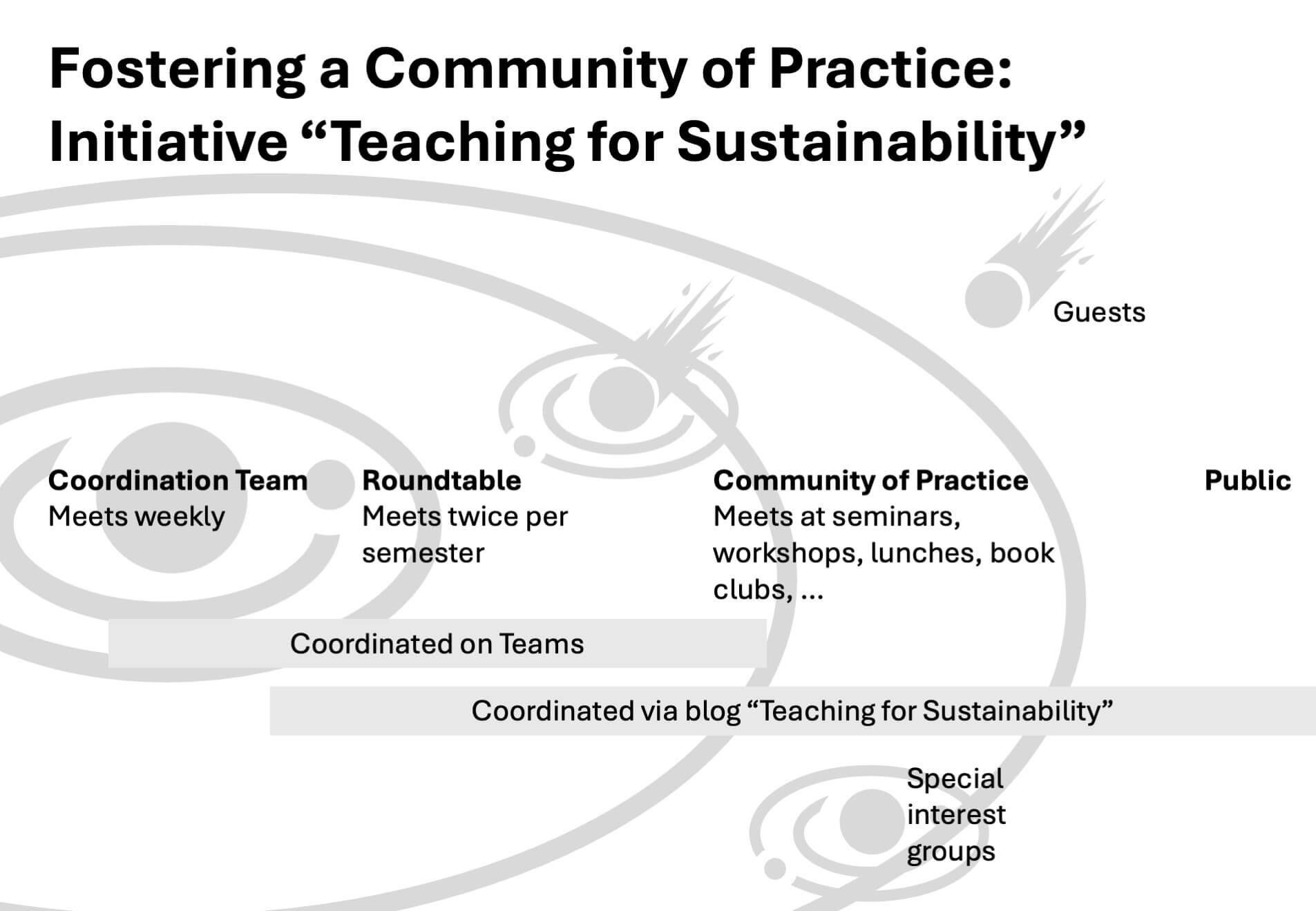

In that paper, we describe the first two years of the initiative “Teaching for Sustainability”: how we used Wenger et al. (2002)’s principles for designing a community of practice in our context, and report on results from a that workshop as well as a follow-up survey. Read the original article for all the details; I am here sharing selected parts.

How we are trying to foster a community of practice for the initiative “Teaching for Sustainability”

(This is the Table 1 in the publication)

Invite different levels of participation.

We work with three main circles of involvement:

- The “Community of Practice” (CoP) is an open network for all interested teachers at Lund University. Teachers join through our MS Teams group, by opting in to an email list, or by joining events.

- The “Roundtable” consists of voluntary (in contrast to officially appointed) representatives from all faculties. Its role is to ensure information flow and collaboration between different parts of the university.

- The “Coordination Team” engages in operational planning and implementation based on recommendations and wishes from the Community of Practice and the Roundtable.

Members may choose to play central roles or remain in the periphery in any and all of the circles above, and to change their roles over time. In addition to those three circles, we also support overlapping sub-communities, for example on exploring Serious Games in teaching and learning (see below).

Create a rhythm for the community.

Interacting and practising together regularly is the backbone of a CoP.

- Members of the CoP meet both in formal structures like courses or seminar series, as well as informally, to share experiences, discuss external input or own teaching practices, and provide mutual support.

- The “Round table” gathers twice per semester in a meeting with agenda and protocol.

- The “Coordination Team” meets weekly, organised around both an agenda and a protocol.

Finding a good rhythm for each of the circles is crucial to neither overwhelm people nor let them forget about the circle or let them experience the work as inactive.

Develop both public and private community spaces.

To accommodate different preferences, and to keep the community open for new ideas, we work in different arenas. For the CoP, the Roundtable and the Coordination Team, we have separate regular meetings and private MS Teams groups. We aim to keep the threshold to join each of the groups (or to linger at the edge) low, by for example sharing meeting notes, event summaries, etc. on our blog, https://teachingsustainability.blogg.lu.se/, and by sending out monthly compilations of news to an email list. At the same time, we experience formation of small subgroups that rely on and support each other also in professional contexts outside of our initiative.

Open a dialogue between inside and outside perspectives.

We regularly invite outside speakers to our events, organize “public viewings” where we attend online seminars together in one room, and participate in regional, national, and international networks to ground our work in the developing best practice in the field. We have recently started a book club to explore new perspectives. We regularly extend open invitations to our events, for example, our academic development courses routinely use the final presentation of course projects to invite other interested colleagues for discussion and feedback.

Combine familiarity and excitement.

Members need both predictability, e.g. in routines and regular meetings, as well as excitement, e.g. spontaneous events and new input.

Within all three circles, we strive to engage in what Martinovic et al. (2022) call “generous scholarship”: In addition to regularly running courses, seminars and workshops, we focus on investing time and energy in building supportive, caring relationships, and to react to needs as they come up.

Design for evolution.

A CoP depends on the voluntary contributions of its members, their interests and goals. As these change with time, the CoP also needs to change and adapt. The main motivation of the study presented here is to understand the needs of LU teachers as we develop our work. For example, a sub-CoP has formed around Serious Games, where we initially ran a seminar, then a follow-up, and where since engaged teachers have taken over inviting each other to test games together. We have also started running monthly “Transformation Thursday” lunch meetings, where the “Coordination Team” and often also members of the “Roundtable” are available for drop-in meetings in one of the cafés on campus to anyone who wants to talk about teaching and sustainability, and we run a lot of “on demand” workshops in pre-existing networks.

Focus on value.

Reflecting on the value of the community helps to show the value to Lund University and to sustain motivation.

So much for the theory — how has this played out in practice in the first two years of the Initiative “Teaching for Sustainability”? For that, we asked different survey questions

What hinders teachers’ progress?

(This is the section of the same name in the article)

Respondents to the question “what hinders your/our progress” shared various obstacles that prevented their ability to teach for sustainability, which generally fit into three themes: time, resources and support, as well as unclear leadership roles with one theme being most prominent – lack of time was mentioned by seventy percent of respondents to this question. This included lack of time to read literature, learn from others, develop new course content, prepare for classes, as well as reflect upon or evaluate their teaching to make meaningful changes. Respondents also stated they have too little time with students – or students do not attend classes – to feel like they can support students in this way.

Similarly, respondents expressed frustration at the perceived limited resources and support to develop their own competence. Seemingly, teaching is perceived as an individual and isolating endeavour, with insufficient venues to share experiences or seek inspiration from others. Moreover, several mentioned limited support from their faculties, departments, or directors of study, signalling a lack of support by leadership or the example they provide.

This speaks to the perception of unclear leadership roles – who has the responsibility or mandate to ensure coherence between the strategic documents and systems of support across the University, faculties, departments, and degree programmes. Respondents expressed frustration at reduced administrative support, long timeframes for changing syllabi, overemphasis on research, limited recognition or time allocated for pedagogical training, and job insecurity as barriers that hinder their progress to integrate sustainability into teaching. For example, one respondent stated, “[d]on’t assume teachers will spend time on important activities without support or recognition of their value from the University”.

What more can Lund University do to support Education for Sustainability?

In response to our survey, teachers provided concrete ideas of what Lund University could do to support them better. Below are some example quotes from the article, corresponding to the hinders identified above.

Time:

- “Give us paid time to work with this, rather than having to squeeze it in between other activities.”

- “Paid time for development and reflection, perhaps together with students.”

Resources & Support

- “Create opportunities for peer-to-peer sharing of experiences, pedagogical approaches, or teaching materials.”

- “Provide seed funding to teachers to develop pedagogical competence, spend time on course development, etc.”

- “Establish a prize or recognition programme for teachers that exemplify best practices.”

- “Provide dedicated workshops or courses for teachers.”

- “Introduce a mentoring programme for new teachers and/or those that wish to learn from more experienced teachers”

Unclear Leadership Roles

- “Have a more strategic approach that includes long-term funding for strengthening teaching for sustainability at LU.”

- “Create more demand for teaching sustainability, including pressure for faculties to include sustainability in all degree programs.”

- “Motivate teachers that are not focussing on sustainability.”

- “Clear and specific leadership that overcomes silo (or faculty) thinking.”

- “Move beyond arguing for why it is good; ensure sustainability permeates all levels of leadership, administration, and decision-making.”

Next steps for the Initiative “Teaching for Sustainability”

Informed by all this, we formulate next steps that we want to address (again, directly taken from the article):

- More time and resources for individual teachers to advance their teaching for sustainability.

- Support for shared resources at the collegial level, such as workshops and seminars, to support networking and learning between teachers. This support could be:

- administrative support, for example communication and logistics.

- personnel support, for example low percentage funding of positions within departments to coordinate teams of teachers for sustainability.

- infrastructure to share inspirational content, e.g. a database of good practice examples.

- Competence development opportunities for teachers that fit teachers’ busy schedules. To allow for this, academic developers need opportunities to specialise on teaching for sustainability, with time to improve resources for teachers, have consultations with teachers, and connect to networks.

- Further translate the commitment to teaching for sustainability at the university level, seen in strategic document, into support of the operationalisation at the study program level. This could, for example, be done through seed funding of transformational teaching projects, or awards and recognition of teachers advancing education for sustainability.

Lastly, we conclude in the article:

“Lund University was recently ranked third globally in the QS World University Rankings: Sustainability (Lund University, 2024b), which can be seen as recognition of existing work, as well as aspiration to continuously strive for. Many teachers at Lund University are highly engaged and working hard to prepare students for “the end of the world as we know it” (Stein et al., 2022), with current activities and new ideas, as seen not least in the survey results underpinning this paper. Meanwhile, a majority report lack of time as a major obstacle, which makes us wonder if the lack of time results in less teaching for sustainability or if the teaching is done anyway, possibly at high costs to teachers’ health and social life – in itself a sustainability problem. Here, we see a need for more clarity on roles and responsibilities, and coordination of efforts at different levels – from the individual level, the program board to the overarching university level, to create synergies and mutual learning.

Despite focussing this article on our own work and the work of the teachers within our TfS initiative, we wish to acknowledge the many other stakeholders working to enhance teaching for sustainability and education generally at Lund University. We recognise that they are likely struggling with similar obstacles that we have identified, and that due to the decentralised nature of the university, we might not even be aware of their efforts. If this is you, or you know of someone we should know, please do reach out! We would love to connect and join forces towards our shared goal, to foster a culture that enriches the educational experience for both educators and students, working for a sustainable world.”

So this is where we were at at the end of last year. A lot has happened since and we’ll update you on that soon, but it is nice to have this finally published!

Glessmer, M. S., Curtis, S., Thoni, T. (2025). Two years of the initiative Teaching for Sustainability at Lund University – understanding challenges and exploring opportunities. In: Connecting Teachers – Changing from Within. Proceedings from the 2024 Lund University Conference on Teaching and Learning. Editors: Johanna Bergqvist Rydén and Marita Ljungqvist. Lund University. ISBN: 978-91-90055-50-2; DOI: https://doi.org/10.37852/oblu.343.c766

Access the whole book online here: https://books.lub.lu.se/catalog/view/343/521/2123;

Lund University (2024b). Lund University ranked third in the world in QS Sustainability Ranking. https://www.lunduniversity.lu.se/article/lund-university-ranked-third-world-qs-sustainability-ranking (accessed 6/2 2025)

Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Suša, R., Ahenakew, C., & Čajková, T. (2022). From “education for sustainable development” to “education for the end of the world as we know it”. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(3), 274-287.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard business press.