On “Our time: Finding Hope in a Climate Crisis” by Alasdair Skelton (2026)

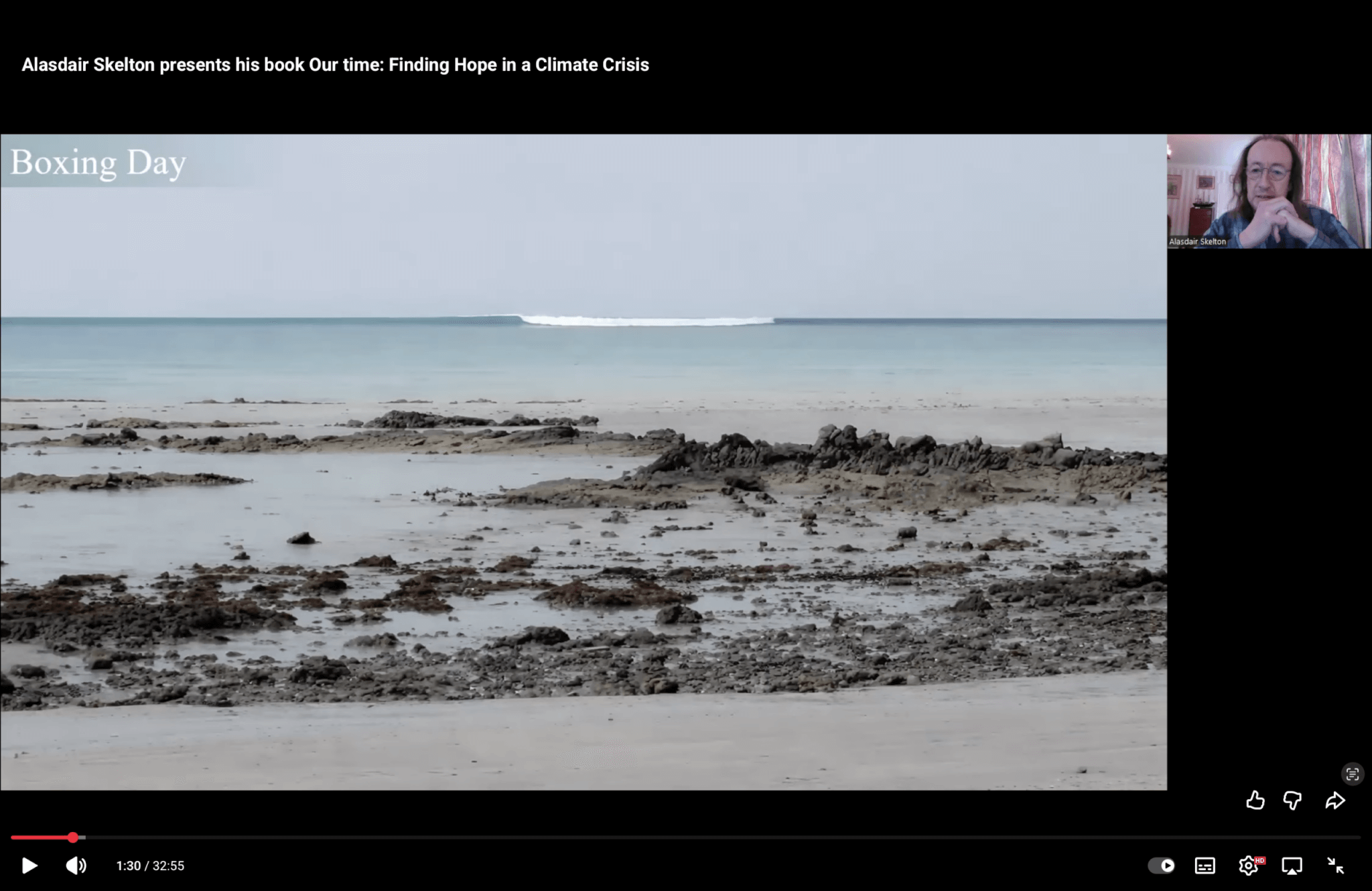

When the picture in the featured image (a screenshot from the presentation of Alasdair Skelton’s presentation of his book “Our time: Finding Hope in a Climate Crisis“, watch the recording on youtube!) came up yesterday at the beginning of my lunch break, I felt it in my stomach. I don’t know anything about the coastline shown there, I didn’t know where the picture was taken, but I do know that the water looks off. Very off. There should not just be one single, breaking wave crest on the horizon and no other waves in sight. There should either be many more wave crests visible at once, or none, but if there is only one crest all the way to the horizon, that means that the wavelength is too long. Normal wind waves are only a couple of meters long. Swell waves are a couple hundred meters long, but still you would see more than one wave crest at once. So either what’s on the picture is AI (and AI is terrible with water, so something like this might happen) or — and that is what I felt in my stomach — it must be a tsunami. For me, seeing this image triggered an instinct reaction of fear, before I could even read and process that it says “boxing day” in the corner. This is the clue that this a picture of the boxing day tsunami of 2004, which claimed approximately 230,000 lives.

I remember the boxing day tsunami very well. I was halfway into my fourth year of studying oceanography, and before that, tsunamis were more of a theoretical concept, quite easy and quite boring. Tsunamis are shallow water waves, where the phase speed only depends on water depth, so if you know something about the bathymetry of an ocean basin and the trigger point from which a tsunami is spreading in all directions, you can calculate its speed as sqrt(gH). If you don’t know the bathymetry, H=4km is a good rule of thumb. Then, the tsunami travels at approximately 200m/s, which is almost 800km/h, a similar speed to a jet plane. Even with that approximation, it’s pretty easy to pretty accurately predict when a tsunami will arrive where, if you only know where it was triggered and when. Tsunamis had happened in the past and they would happen again, but still. And then, boxing day 2004, they suddenly became real for me.

Since 2004, a lot has happened. A lot of research on tsunamis that supported, among others, installation of monitoring and warning systems. More tsunamis, including the one of 2011 that caused the Fukushima disaster. You cannot prevent tsunamis from happening, you can just try to get out of their way when they happen, and try to prepare for them to happen before they do. But there are other physical processes in the Earth system that are also extremely well studied so we know exactly what is happening once they have been triggered. We know that adding CO2 from burning fossil fuel to the atmosphere destabilizes the climate system, and we know that we have done that and are still doing it. We know what the consequences of that will be if nothing changes. In contrast to a tsunami, there is no running away from climate change. But also in contrast to a tsunami, there is something we can all do to change the trajectory we are on. We cannot stop a moving wall of water, but we can very much limit, even stop, adding CO2 to the atmosphere. And with that, we can influence how bad things are going to get.

In the book, Alasdair tells a beautiful, personal story of climate change and of finding hope despite of it through taking action, through being our children’s, and each other’s, hope. But also through recognizing that the unexpected can and does happen, which he illustrates with the beautiful image of old oak trees that were planted to grow strong and straight (with birches around to make sure they would grow upwards to the light) to be harvested and made into ships, at a time where nobody might have imagined that ships would be made of steel not so far into the future, and that those trees would grow old in peace and would not be needed for shipbuilding.

For me, the physical reaction to seeing that picture above is based on my training as oceanographer, maybe on my daily practice of that muscle of looking at waves and thinking about physics (#WaveWatching!), on recognizing wave theory when I see it in real life (or a picture). But how many others felt it in their stomach when they saw that picture? How much training do you need to understand the warning signs of a catastrophe that is getting really close? Who would you listen to if they told you to run, or to otherwise change your behavior? MacInnes et al. (2026) suggest that family and friends play a big role in climate change communication, as do “people like me”. Which means people like you, people like us. We need to talk with each other about the climate crisis, so that what is extremely clear from the research gets implemented in policies, in behaviors, in our lives. I ordered Alasdair’s book half an hour ago, right before starting to write this post, because now I look forward to reading it to see how the story that so touched me in pictures and narrated by Alasdair will touch me in written text. And so I can give the physical book to other people, and discuss it with them. In Sweden, you can buy it via Akademibokhandeln, and for the rest of the world, check out the book’s website for how to get your hands on it. And while you unfortunately don’t have access to the book yet, while you are waiting for it to arrive or making it to your local bookshop, you can watch Alasdair present it on youtube. You can watch it with friends, like I did yesterday with Terese, or with family, or with people like you, and you can talk about it. And then, you might just find hope in the climate crisis.