Currently reading “Academic identities and teaching wicked problems: how to ‘shoot a fog’ in a complex landscape” (McCune et al., 2024)

Teaching about sustainability is teaching about a (or many) wicked problem(s), and that is a challenge for teachers for many reasons. We need to, for example, teach how to work with wicked problems in general (although there is some helpful literature out there that we can start from). But when doing this, we need to drastically reconsider the traditional idea of the teacher being “the expert” (also one aspect in the “spiral of silence“). In a topic where there is no one right answer, being the expert is not possible in the traditional sense, so we need to figure out how to deal with that. How do we integrate it with who we think we are as academics, and how do we negotiate who we are with academic colleagues and all the other people in different contexts, with different agendas and values and ways of knowing etc?

The article “Academic identities and teaching wicked problems: how to ‘shoot a fog’ in a complex landscape” (McCune et al., 2024) explores this through narrative analysis of 20 teachers who are teaching wicked problems in a big range of different contexts, and a comparison group of 15 teachers who were not, and interpret them through Wenger-Trayner’s “landscapes of practice”. They find that some of their study participants working with wicked problems had decided, or come over time and through passionate engagement, to embrace identities that included a lot of work on and across boundaries with e.g. other disciplines. They had created a coherence in their identities, values, roles, practices, focused on the object of “their” wicked problem. This can then in turn help reduce friction between roles as teacher vs researcher, and lead to acknowledging and valuing expertise from students or others outside their academic field. But how can we support teachers in this?

Policy makers can, according to McCune et al. (2024), support teachers who are bridging between different disciplines by reconsidering workload models (and I can attest to how much energy goes into boundary work!), precarious contracts (again, I am SO GLAD that I can do this work from the comfort of a permanent position!), recognition (traditional measures of academic success don’t represent non-traditional, non-ivory-tower ways of working…) and reward. Also “giving permission and space to challenge traditional academic roles” is so important! McCune et al. (2024) also suggest reflexive practice on the issue in pedagogical training, discussion of role models who successfully navigate the challenge, and also explicitly addressing the issue of identity and the emotions and values that are part of it.

So far, so good, but somehow this article leaves me disappointed; I had had the unfounded hope that they would give more concrete advice on what teachers themselves, or academic developers to support teachers, could do (which, to be fair, was only based on the mention of “how to” in their title, and since I am not really sure that I understand what is meant by “shoot a fog”, maybe I misunderstood the whole title?). But here is what I think we might try as academic developers (which actually basically falls under the points they make above, except that my examples are a little less abstract):

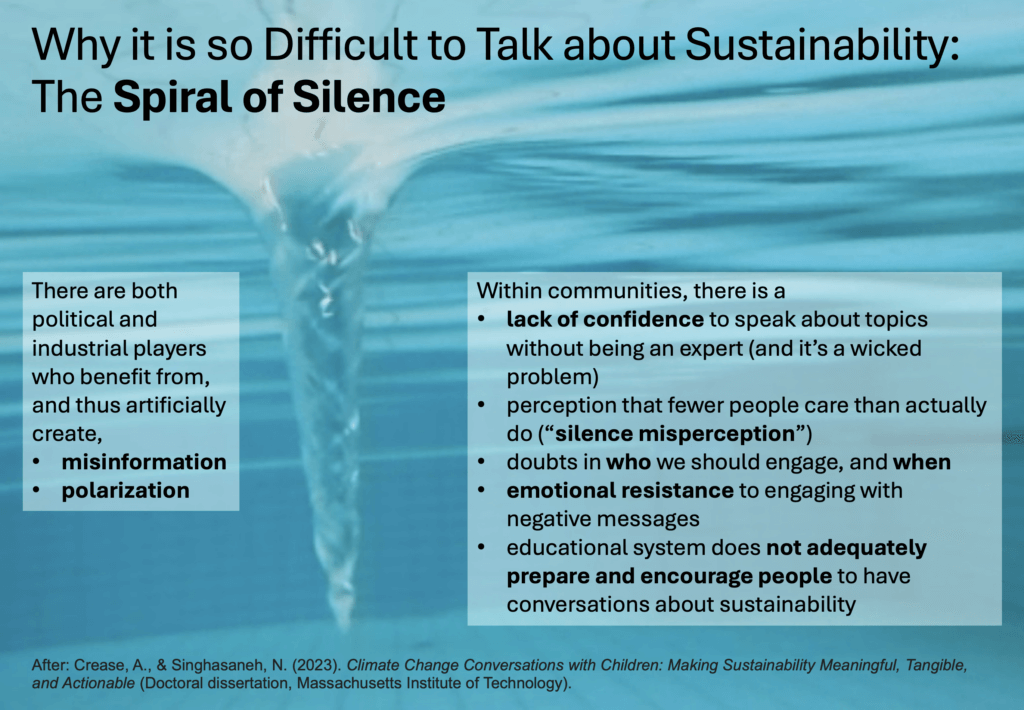

- talk about the “spiral of silence” (see image below), and especially the aspect that many of us lack the confidence to speak about topics we aren’t experts on, and that in case of wicked problems, nobody has all the answers

- offer support for figuring out what really matters to us, for example through “even over” exercises, or positionality mapping

- disclose our own struggles, past and present, with working on wicked problems. I remember Kim Nicholas saying years ago how she had decided that she was only going to work on projects that in some way contribute to sustainability. I thought that was equally completely inspiring and unattainable back then, and only recently realized that I have actually partly shifted, partly reframed, my own work so that now most of what I do contributes to improving teaching for sustainability, even when I am teaching courses where that is not explicitly required. And that is a lot more satisfying and feels coherent with who I want to be and how I want to live my life!

- provide tools to build support networks. Those tools could be events that we organize where people have the chance to connect on topics relating to teaching for sustainability, but maybe also looking back at ESWN’s mentoring map, except now with the focus on building a supportive network around teaching for sustainability, rather than “just” to support a career in general

- I think maybe even reflecting on models like the “landscapes of practice” helps understand where conflicts can come from, and to some extent also how to navigate them, but also where to look for allies and support, both on the wicked problem at hand, and on navigating this weird space more generally.

And as always, building community to navigate all of this together…

P.S.: I found the McCune et al. (2024) article through Stockholm university’s Centerum för universitetslärarutbildning’s newsletter (which you can subscribe to here), where they always highlight very interesting articles (although mostly in Swedish)

McCune, V., Scoles, J., Boyd, S., Cross, A., Higgins, P., & Tauritz, R. (2024). Academic identities and teaching wicked problems: how to ‘shoot a fog’ in a complex landscape. Higher Education Research & Development, 43(1), 166-179.