Our seminar today: “Serious Games in Teaching for Sustainability”

Here comes my informal summary of today’s seminar on “Serious Games in Teaching Sustainability”. A more formal summary will go through the official channels shortly (or that’s the plan… :-))

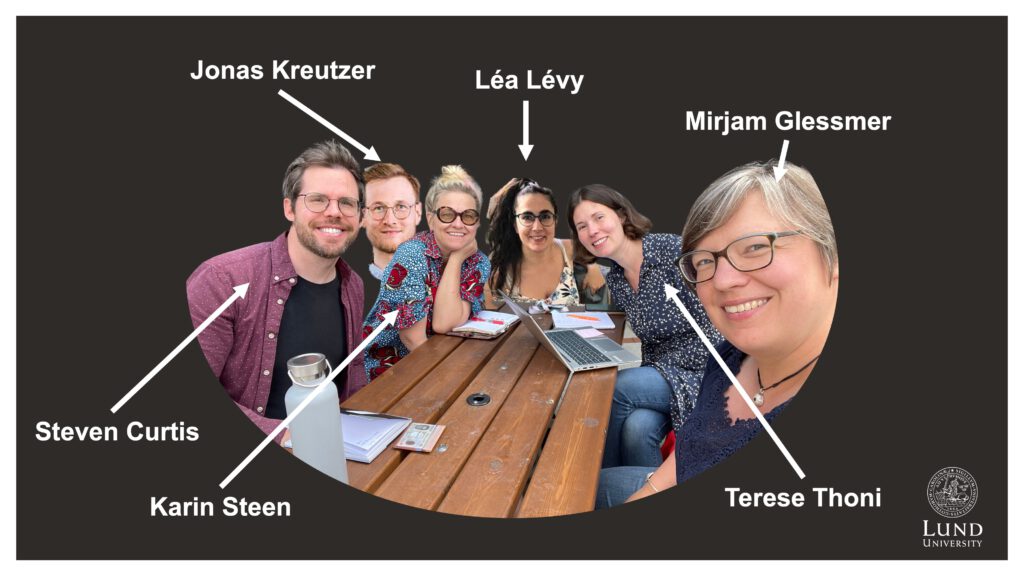

Today, together with my colleagues Léa Lévy and Jonas Kreutzer, I ran the seminar “Serious Games in Teaching Sustainability”. This seminar was born out of the “Task Force on Education for Sustainability”, that my colleagues Steven Curtis, Karin Steen, Terese Thoni, and myself are running together. As academic developers at different units across LU and the educational coordinator at the sustainability forum, our goal is to build community and resources to support teachers in teaching for sustainability. Below, you see all of us — and you are welcome to get in touch with any and all of us if you want to talk about teaching sustainability! (Please excuse the bad “photoshop job” (PowerPoint in reality) of putting all of us in one picture…)

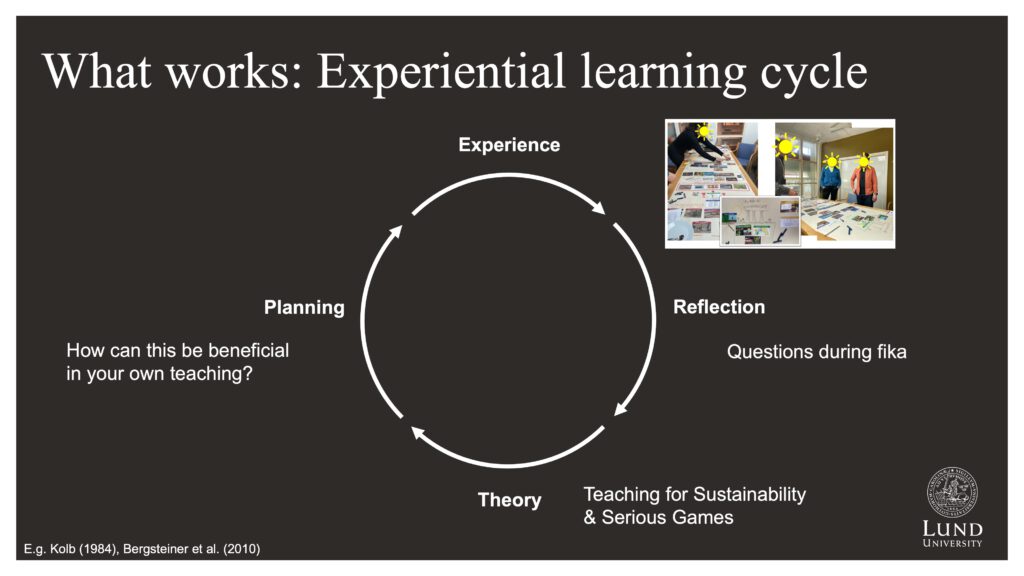

The agenda for the 90 minutes (+15 minutes coffee break — with very nice and sustainable vegan sandwiches!) was pretty full. We wanted to provide participants with the experience of playing a serious game (the biodiversity collage, developed by the French NGO of the same name, that I have written about before), and use that as the entry point into an experiential learning cycle (e.g. Kolb (1984), or Bergsteiner, Avery & Neumann (2010) for a much better way to present the same concept). After experiencing a game, we would enter reflection, then add a little theory, and then go into planning of how games can be used in participants’ own teaching. From there, hopefully, they will implement something, gain an experience, reflect on it, maybe consult more theory, and modify their planning. Caught in the experiential learning loop, oops! :-)

First, we started out with an ice breaker. We asked participants to discuss in groups of 2 or 3 what their favorite meals are, and how many ecosystems are involved in bringing all the ingredients together. That is maybe not a typical ice breaker in an academic development context, but for this specific seminar, it makes a lot of sense to start thinking about ecosystems in a new and different way. Léa’s example is sushi: We have rice grown in wetlands, salmon that needs both rivers and the ocean, algae that grow in the ocean (I know, Léa, technically they don’t go in sushi…), ginger, which apparently grows in well-drained soil, soy for the soy sauce, possibly sesame, cucumber, all kinds of other stuff. Gets very complicated very quickly! Who would have thought that we need so many ecosystems for a simple meal? One group of participants shared that they had discussed about the cheese on their pizza — you don’t just need the cows, but the cows also need to be fed, …

From the ice breaker (which we also use when we play the “biodiversity collage” in its full form, we moved on to the two “starter” sets of the biodiversity collage. One deals with an oceanic ecosystem and how shark fisheries can lead to the breakdown of mussel harvesting, the second one with the French countryside and what happens with the species diversity when you take away all the hedges and groves. Both sets are relatively easy, but already pretty complex and interesting to discuss. Also very interesting to see how there is this urge to explain changes with climate change, even when we are still trying to look at the ecosystems in equilibrium, before disturbance. I remember that was my first idea, too.

Below a picture of many engaged participants, and a facilitator who knows when to step back and let participants develop their own ideas, and when to engage in discussions with them or intervene…

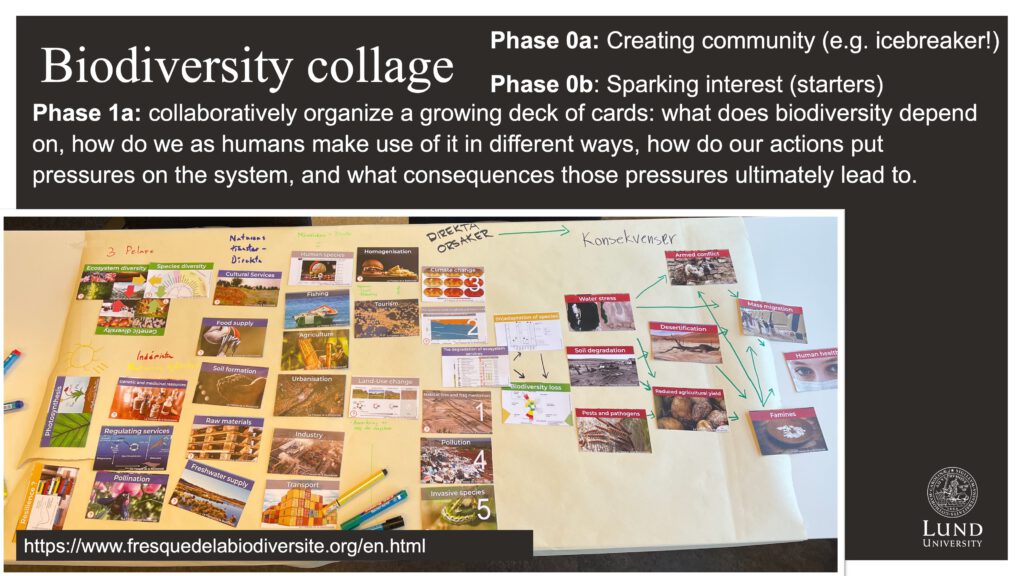

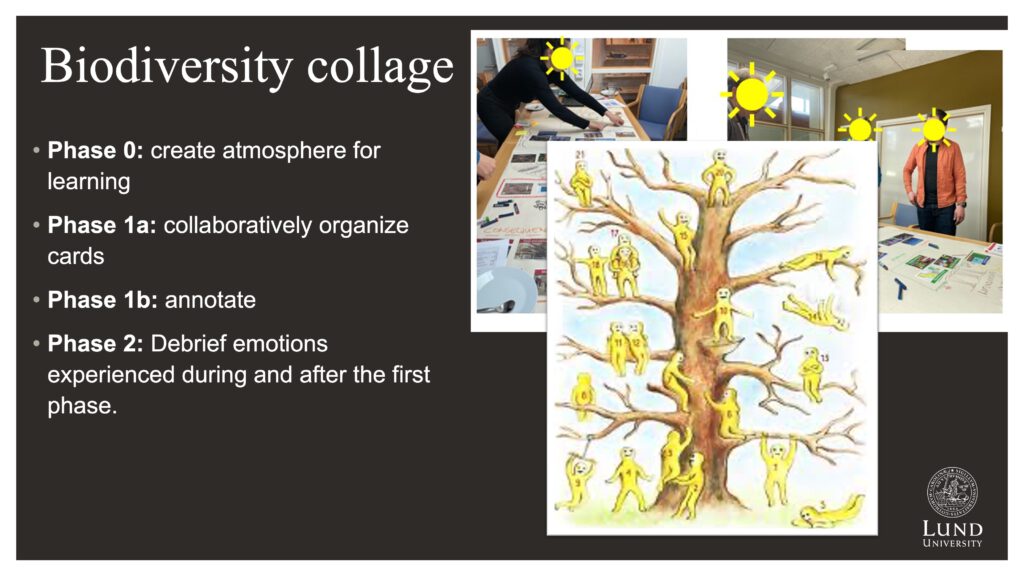

Now participants have first-hand experience with the way the game works in that cards need to be organized and stories told, we talk the participants through the rest of the game.

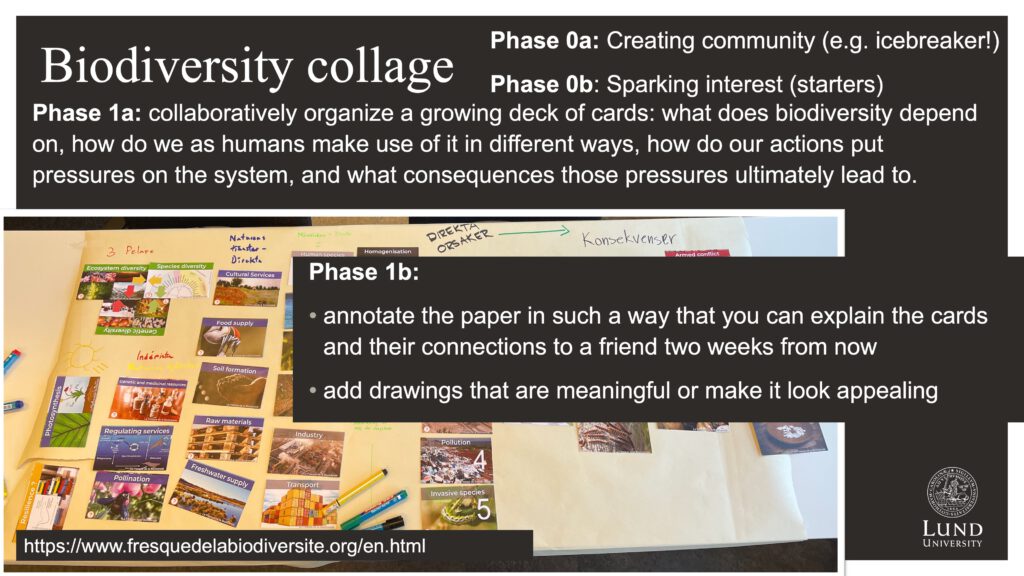

In Phase 1a, participants in the game collaboratively organize a growing deck of cards that deals with aspects of what does biodiversity depend on, how do we as humans make use of it in different ways, how do our actions put pressures on the system, and what consequences those pressures ultimately lead to.

In the slide below, I am showing one example of what the final arrangement of the cards looked like when I facilitated the biodiversity collage a while back.

What happens then, in Phase 1b, is that the paper is being annotated in such a way that participants can “explain the cards and their connections to a friend two weeks from now” (or that is the goal that we ask them to work towards. I’m a bit doubtful that this always works out — I know it did not work out for me that way when I participated for the first time!).

In this phase, participants also add drawings that are meaningful to them, or make the collage look appealing, in order to gain ownership to the product and build some kind of emotional connection that will help them remember.

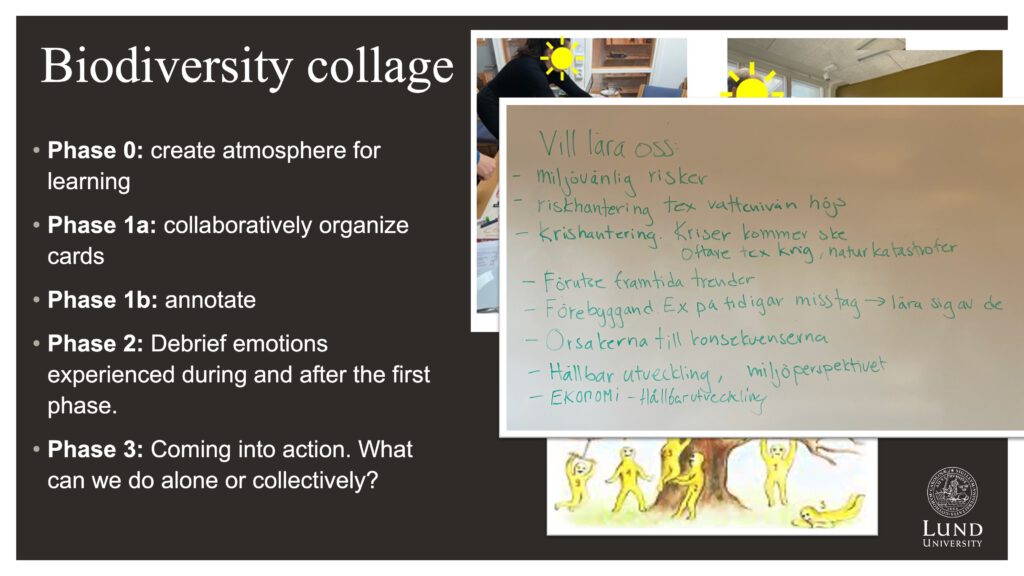

Next, we enter Phase 2, which is about debriefing emotions experienced during and after the first phase. There are different ways to do it, but one that I like a lot is using the BLOB tree. Participants are asked to identify one or more little people in the tree that they feel represents their emotions at that time. For the students we work with, and, I would guess, most students, this is one of the very few times that they are asked to talk about their emotions in a university context. Which they really appreciate, and which we find is super important so that a) they are not left alone with the despair or overwhelm or whatever they might be experiencing, and b) they can build community around feeling angry and wanting to do something (anger actually being a very productive emotion sometimes! At least if not overshadowed by depression. Read blog posts summarizing literature on that here and here). Many students actually also report hope and a feeling of community, because they found in the discussions that they aren’t the only ones that are concerned, and that there are peers that share their worries.

Lastly, we have Phase 3, which is about “coming into action” (or at least moving in that direction). There are many different ways to structure this phase — most recently, in the Master on Risk Management, we asked students to brainstorm what they want to learn about during their studies that will help them cope with the challenges we are all facing. And — thanks for the question, Maria — of course this was collected and followed up on by the course responsible teacher, pointing out where many of those topics are situated in the curriculum, and where they might learn about the ones that aren’t already on the schedule.

After this, it was time for a coffee break combined with some reflection questions.

After the break, we went into a bit of theory around teaching sustainability.

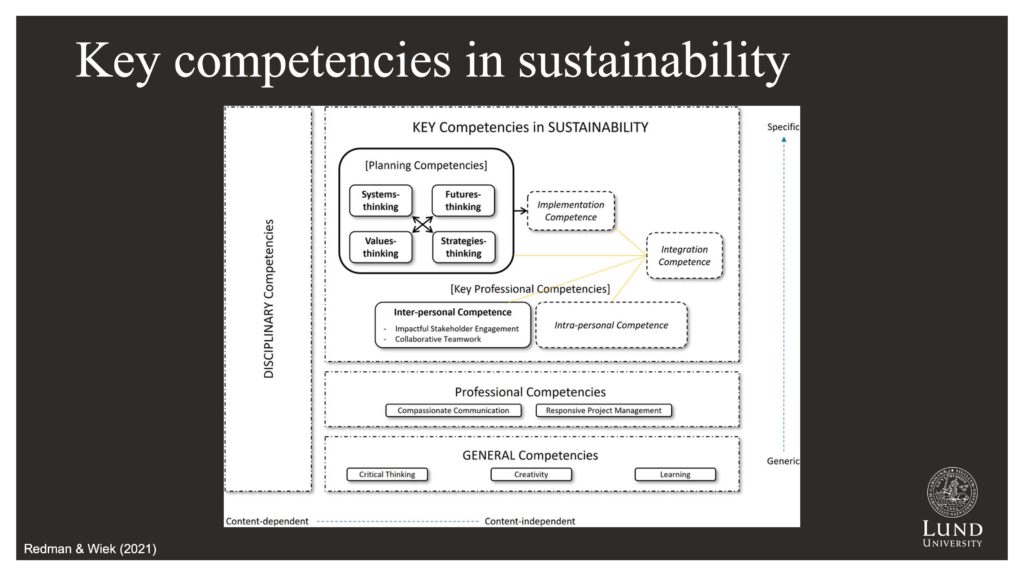

First, I pointed out a framework for key competencies in sustainability (Redman & Wiek, 2021). Sustainability competencies are very complex and not typically on any syllabus (yet) — but we can address them in many different ways (and there will be a course at LU starting in January, run by Steven and Karin, that you can sign up for here).

Then, some context on serious games. Basically, everything that has game characteristics but a purpose beyond pure entertainment can be categorized as a serious game (Ouariachi et al., 2019). In this seminar, we only look at a very specific type of games — everything in the Climate Fresk (my experiences with it here) family or derived from it — but also simulations, role plays, and many others count as serious games!

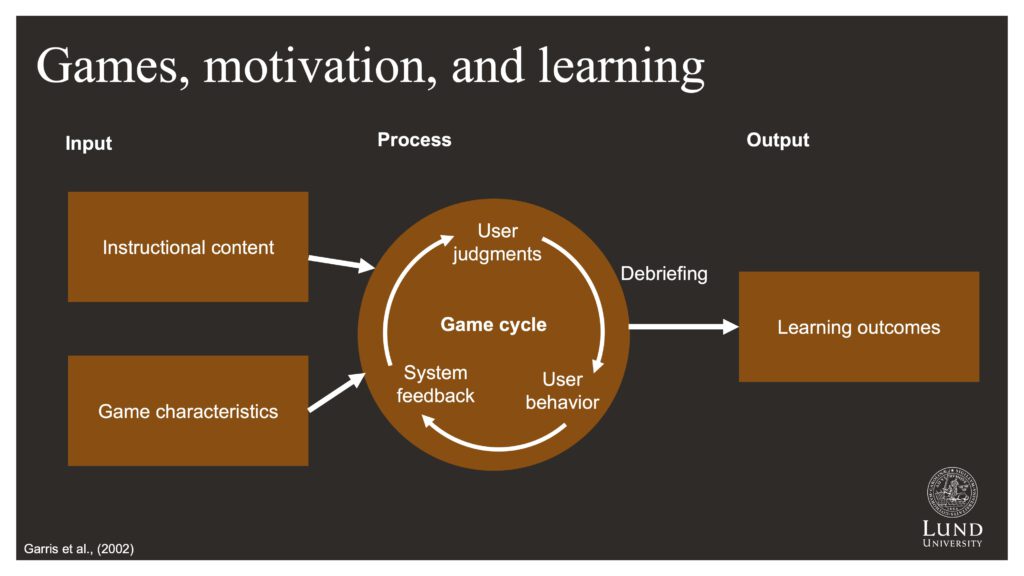

One model that is helpful when thinking about games, motivation, and learning is the one by Garris et al. (2002). I write about it in a lot more detail here, but in a nutshell: There are inputs into the game: The instructional content (in the case of the Biodiversity Collage it’s the IPBES report, a report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services similar in the way it has been put together and negotiated to the much better-known IPCC report), and the game characteristics (is the game world sufficiently far from real life, with no consequences for real life? What happens when rules are broken? Do participants feel that they have control over what happens? Is the level of challenge appropriate?).

Building on those, the “game cycle” is what makes a good game addictive and lets players experience “flow”. The three components of the game cycle are 1) User judgment; typically measured as self-reports of interest (usually games are perceived as more interesting than conventional instruction), enjoyment (fun & sense of achievement), engagement, and feeling of mastery. Also relevant is how absorbed players become in the game and that there is confidence in their actions, i.e. failure without any real-world consequences, 2) User behavior; if the conditions above are right, users show “persistent reengagement”, i.e. active engagement, intense effort and concentration, and returning to the game voluntarily and unprompted, and 3) System feedback; It needs to become clear that the current performance is slightly below good enough, but that with a slight increase in effort and maybe more practice, the goal will be attainable. And then there needs to be a new desirable goal just sliiightly out of reach…

And from that, we will hopefully reach the intended learning outcomes. Even for one and the same game, these can be different depending on context: In the biodiversity collage, it could for example be to situate a specific course or topic in the wider context of biodiversity loss, or to understand the complexity, or to learn to talk about concepts with peers, or to raise interest, or many more.

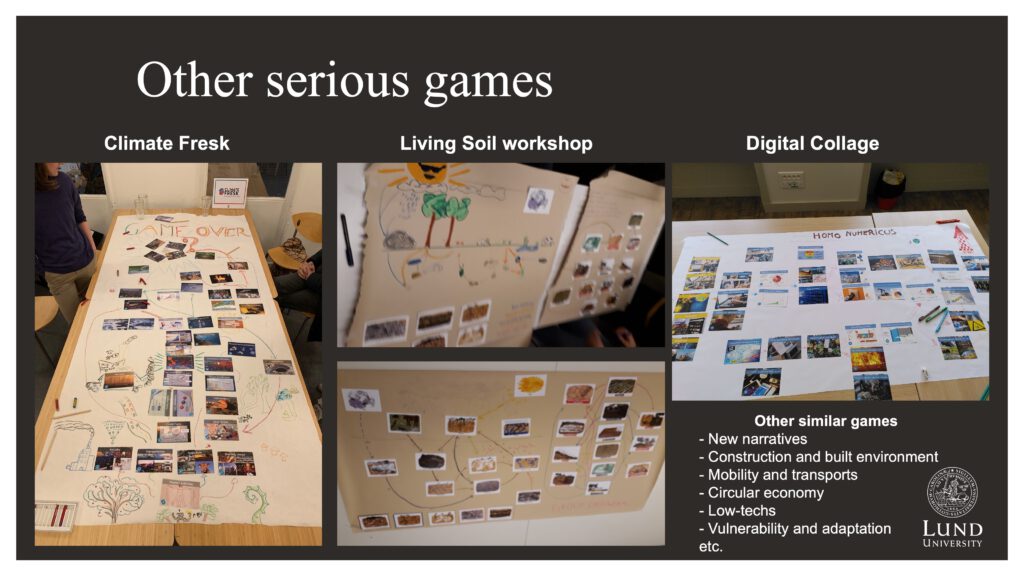

Next, Léa presented other serious games, all structurally and mechanically similar to the biodiversity collage, that she has experiences with (and here she needs to provide us with more info later, as she promised to do :-)) But one that I am especially curious about is the “digital collage” about footprints of what we do online. I will need to play that one fairly soon!

Léa then shared some more of what it means to play this type of games in practice.

For example, one teacher can handle 2 tables (i.e. two games with max 8 participants each) in parallel. And she does that impressively — for me, having one table at a time is challenging enough still… But that stresses how we need to involve a lot of people as teaching assistants, and here we are working on training students as facilitators. Both, selfishly, because we need them, but also because this is a very good way for students to find community of other concerned and engaged students, and to do something that feels meaningful (and that is definitely the feedback we are getting). Also training colleagues can be an option (that’s how Steven, Gerhard, and myself ended up training as facilitators for the biodiversity collage…).

Léa also talked about how teachers can use existing games or create their own. Our colleague Alexandra, for example, created a game inspired by the Climate Fresk, but tailored to her specific course and learning outcomes. I will hopefully share her report on that here some time soon!

And then Léa shared her experiences with different ways to facilitate the reflection and action parts (Phases 2 and 3). She especially liked her recent experiences with assigning roles to everybody at the table to talk about solutions, and experiencing how the best solutions from one perspective are totally not desirable from another.

Léa then talked about a workshop she gave yesterday in her course on groundwater engineering (that woman is incredible, I don’t know where she takes all that energy from!). There, she used the game to contribute to very fact-based, chemistry learning outcomes in addition to opening up the much wider picture of how the course content fits into context. (Again, hopefully Léa will have time to share a bit more about this later!)

And then she mentioned that she added a really cool competition about the “most pedagogical collage” (remember how participants in step 1b are supposed to decorate and annotate their collages?). Now her students voted on one out of the six produced yesterday, and that one will be used throughout the rest of the course to point to how topics relate to each other and the bigger picture. Love it!

Léa then shared some feedback we got from the first times we ran the Climate Fresk here at LTH, and which encouraged what snowballed into all the fresks & collages etc we are trying to run all the time now:

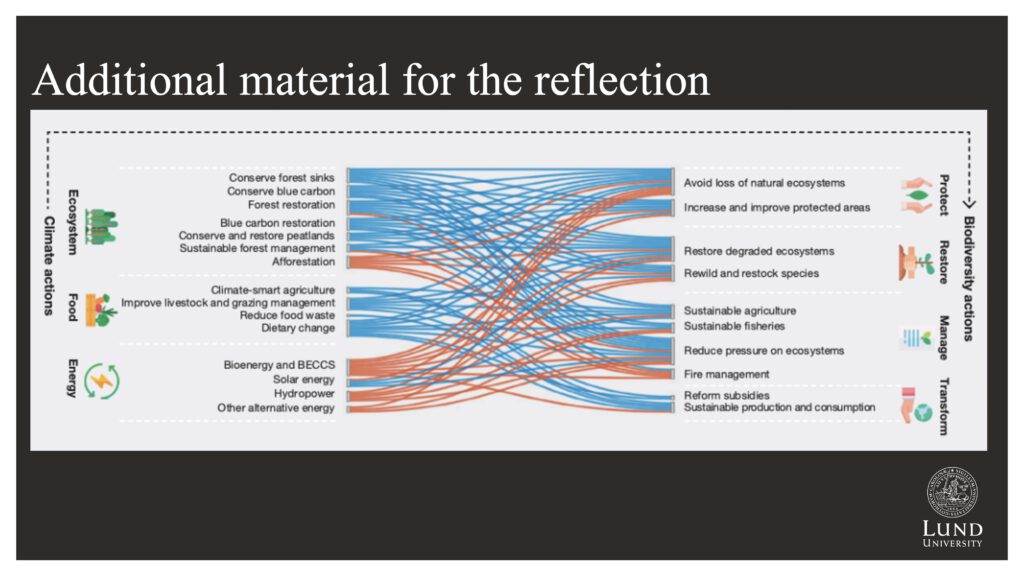

One slide that we skipped today because it wasn’t related to how to use games in teaching (but that I find super important anyway) is the one below, showing how “climate actions”, i.e. measures that are designed to counteract climate change, sometimes have harmful impacts on biodiversity (especially hydropower, bioenergy, afforestation), whereas there are a lot fewer “biodiversity actions” that are harmful for climate. I think this is so important to consider! And this is where the biodiversity collage can be really eye-opening: The last card being dealt in the whole game is the “climate change” card. All the problems related to and caused by biodiversity loss are already on the table and logically connected without climate change even being mentioned. So “just” fixing climate change is not going to help if we want to counteract biodiversity loss and with it all the consequences like armed conflicts, refugees, water scarcity, soil degeneration, and many more!

But then it was my turn again to talk a bit. Do serious games actually work in teaching for sustainability? Of course, as always, the answer is “it depends” (A “review of research on simulations and serious games used in educating for sustainability, 1997–2019” by Hallinger et al. (2020) states “The knowledge base is overly weighted towards ’commentaries’ (55%) and lacks a critical mass of empirical studies (33%). Moreover, the empirical knowledge base is dominated by studies that rely on non-experimental research designs and descriptive methods.”).

It depends on which game is being used (just because a similar game on a different topic works does not mean all games with the same mechanics work), on the implementation of the game (as with all teaching, it almost doesn’t matter what method you use, as long as you use it well. A facilitator can make or break any game…), the learning outcomes of your course (depending on the purpose, the game might “work” or not. It might have lots of positive, un-intended learning outcomes, but you might not see them if you are only measuring the intended learning outcomes), and on the context (for example, in the biodiversity collage, there are “voles” doing things. For most non-native English speakers, that is not a species they have ever heard of, so now I come armed with the Swedish “sork” and German “Wühlmaus” translation. But also depending on culture, some aspects of gamification might work better than others. For our doughnut rounds, for example, the aspect of competition that seems to be very important in a US context, is something that most people in a scandinavian context don’t react well to at all!)

So when we pick games, based on our intended learning outcomes, as with all other teaching methods, we need to consider what we are picking, and why, and evaluate what we are doing and whether it is working. Here, the experiential learning cycle that I mentioned above comes in again… And Jonas later picked it up again when he talked about his experience as teacher creating a new game: how he tests, reflects on how it went, consults theory, modifies, and tests again. So nice for my academic developer heart to hear teachers talk about their approach to teaching in this way!

But in general, we know that having experiences is an important part of learning, and at university we too often focus just on the theory part and omit the other three. So here a serios game can serve as the event that provides an experience that we can use to enter a learning cycle.

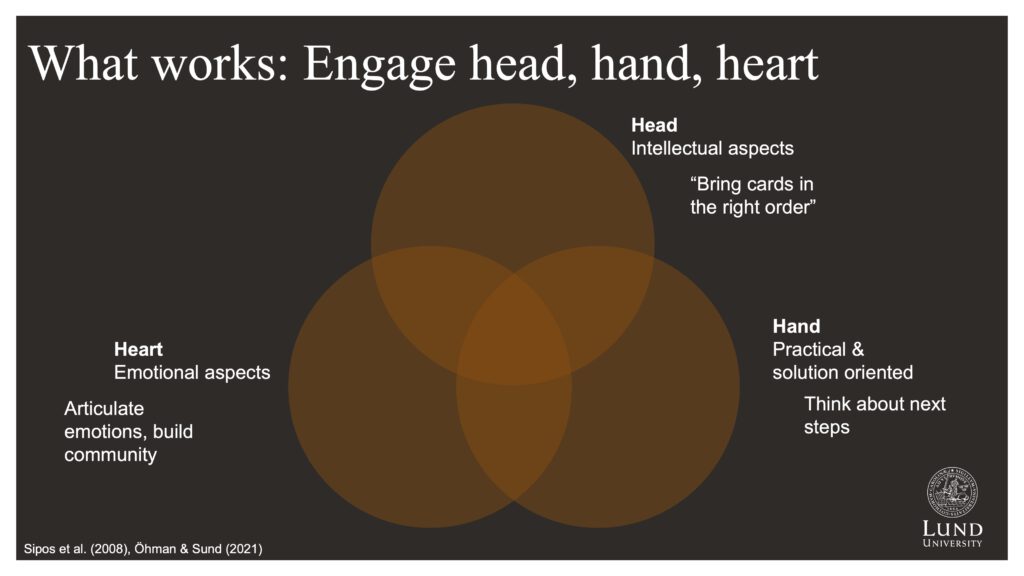

Another thing we know works in learning is to engage not just the head, but equally the “hands” and “hearts” (e.g. Sipos et al., 2008; Öhman & Sund, 2021). We do this with these types of games: The head part “bring the cards in the right order” (VERY abbreviated for “understand a super complex system and show your understanding by ordering cards and talking us through a coherent story line) is used together with practical “hands” aspects like decorating the paper, thinking about next steps, etc; and the “heart” aspects of articulating emotions and building community. The hands and hearts parts help deepening the intellectual aspects, providing motivation and sustaining engagement.

Next, Jonas shared his experience as a teacher. Check out the link or QR code below to get to his excellent website!

In addition to talking about how he uses the experiential learning cycle in his teaching, he also stressed that games do not have to be perfect. He, as teacher in the course, is present when students play, so he can put things into context and discuss possible shortcomings. Maybe the challenge of a non-perfect game is actually more interesting, because what’s more fun than figuring out what your teacher doesn’t know or didn’t include? ;-) In any case, check out his website!

After this, we went into discussions at the tables about what experiences teachers already had, what they thought about using serious games in teaching, etc.. Unfortunately, as always, we had packed way too much into this workshop, so we did not have as much time here as we had hoped. A quick “what is on your mind right now” Menti debriefing showed that participants reported being inspired and wanting to implement something similar in their own teaching. How do I start? When can I play the full biodiversity collage? How can I make sure students connect the game with the course’s learning outcomes? This means that we will have to invite everybody back to work on this together, probably to an even more applied workshops where teachers bring their games/ideas and test them on other teachers, or learn from each other’s experiences. We will see what we can put together, it is on the Task Force on Education for Sustainability’s agenda for our next meeting! We will definitely follow up on this!

Thank you, Léa and Jonas, for all the inspiration and knowledge and ideas you shared today, and thanks to all the participants that were super engaged and made time fly! I look forward to more conversations with all of you! :-)

P.S.: Some resources for teachers at Lund University:

- Website: https://www.ahu.lu.se/en/resources/teaching-for-sustainability/

- Course “Integrating Sustainability Competencies in Curriculum (ISCC)” (deadline to apply 28 November)

- Course “Higher Education Didactics for Sustainability (HEDS)” (deadline to apply 1 December)

- Course (only LTH) “Teaching sustainability” (deadline to apply 20 February)

- TEAMS “Community of Practice (TfS)” (you are welcome to join at any time!)

- and, most importantly, the invitation to contact any or all of us to brainstorm, strategize, chat, and collaborate. We are all happy to talk with anyone interested in these topics!

References

Bergsteiner, H., Avery, G. C., & Neumann, R. (2010). Kolb’s experiential learning model: critique from a modelling perspective. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(1), 29-46.

Garris, R., Ahlers, R., & Driskell, J. E. (2002). Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simulation & gaming, 33(4), 441-467.

Hallinger, P., Wang, R., Chatpinyakoop, C., Nguyen, V. T., & Nguyen, U. P. (2020). A bibliometric review of research on simulations and serious games used in educating for sustainability, 1997–2019. Journal of Cleaner Production, 256, 120358.

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment

Kolb, D. A. (1984). The process of experiential learning. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, 20-38.

Ouariachi, T., Olvera-Lobo, M. D., & Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. (2019). Serious games and sustainability. Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education, 1450-1458.

Redman, A., & Wiek, A. (2021, November). Competencies for advancing transformations towards sustainability. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 6, p. 785163). Frontiers Media SA. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.785163

Sipos, Y., Battisti, B., & Grimm, K. (2008). Achieving transformative sustainability learning: engaging head, hands and heart. International journal of sustainability in higher education.

Öhman, J., & Sund, L. (2021). A didactic model of sustainability commitment. Sustainability, 13(6), 3083.

“Addressing students’ eco-anxiety when teaching sustainability in higher education”, inspired by Eriksson et al. (2022) – Teaching for Sustainability says:

[…] exercises on discussing emotions (for example using check-ins on Menti or Microsoft Reflect, the blob tree with the Climate Fresk, …) or just inviting students to reflect on their wellbeing at the start of a seminar. […]

Applying the Head-Hands-Heart framework to my "teaching sustainability" course - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] in some emotions or practical aspects? Or, as in the image above that maps the activities in the serious game “Biodiversity Collage” (see here for my event summary), the “hands” part is really not very inspiring. Which is true — there is no artifact being […]

Serious games in teaching sustainability – Teaching for Sustainability says:

[…] P.S.: A longer summary (written right after the event with still a lot of adrenaline and no effort to proof-read) is available on Mirjam’s personal blog: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2023/11/21/our-seminar-today-serious-games-in-teaching-for-sustainability… […]