Currently reading “Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model” by Garris et al., 2002

Lots of reading on serious games as tools in sustainability teaching going on here at the moment…

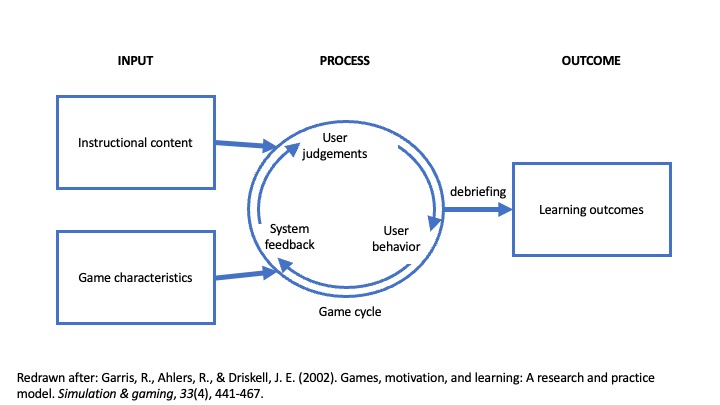

There is something about good games that is captivating interest, generating enthusiasm, and sustaining motivation, and wouldn’t it be cool if we were able to get the same interest, enthusiasm and motivation built up in teaching somehow? Garris et al. (2002) did a literature review and from that created an input-output-process model of how games can be used well for teaching (see above): Instructional content is somehow packaged in characteristics of a good game. Those characteristics lead the player into a cycle of “user judgement” (for example enjoying the experience, being interested in what is going on, …), leading to “user behavior” (like persisting despite being challenged, and sticking to playing the game), and then “system feedback” that keeps the player in the vicious circle of playing the game. When the game is (reluctantly, hopefully, since we are hoping to keep players actively engaged in the learning process for a long time) ended at some point, that will hopefully have led to the intended learning outcomes (possibly with the help of scaffolding and/or debriefing).

Garris et al. (2002) then use their model to structure the literature review.

“Game characteristics” of a game that is successful in the sense described above are

- fantasy: games are separate and different from real life, with no consequences for real life. Fantasy can be separate from what is learned (learning fractions by slaying a dragon), or relevant for the content (learning about aerodynamics by piloting a virtual plane)

- rules/goals: in this fantasy world, the rules are not necessarily the same as in the real world, and when the rules are broken (a ball going outside the field), the game is stopped and things are brought back on track (ball brought back in, game continues). Having rules that are different from the real world (being able to walk through walls) leads to enjoyment. Also having clear, specific, and difficult goals leads to enhanced performance.

- sensory stimuli: similarly to how some people enjoy going on joy rides in amusement parks, according to literature, many people enjoy the feeling of perceiving a virtual reality as real (not me, though, I get really sick every time I try VR goggles!)

- challenge: Goals must be meaningful and not too easy to reach. Not knowing exactly how to achieve the goals, and increasing levels of difficulty motivate players

- mystery: mystery is what creates curiosity in players: complexity, information being somewhat incongruent, novelty, surprise, and violation of expectations.

- control: giving students control (even about features that are unrelated to the task at hand) leads to increased motivation and more learning

Building on those, the “game cycle” is what makes a good game addictive and lets players experience “flow”. The three components of the game cycle are

- User judgment; typically measured as self-reports of interest (usually games are perceived as more interesting than conventional instruction), enjoyment (fun & sense of achievement), engagement, and feeling of mastery. Also relevant is how absorbed players become in the game and that there is confidence in their actions, i.e. failure without any real-world consequences (I think that’s why I generally don’t like games, because I cannot separate failing in a game from failing in reality, which I also deal really badly with…).

- User behavior; if the conditions above are right, users show “persistent reengagement”, i.e. active engagement, intense effort and concentration, and returning to the game voluntarily and unprompted.

- System feedback; It needs to become clear that the current performance is slightly below good enough, but that with a slight increase in effort and maybe more practice, the goal will be attainable. And then there needs to be a new desirable goal just sliiightly out of reach…

After the game cycle, players need “debriefing” to transfer their learning from within the game into the real world learning outcomes that we had. This is typically a reflection about what happened in the game, and how it relates to other learning and the outside context.

What type of learning outcomes can be achieved with a game? Pretty much all: Skill-based, cognitive (on a declarative, procedural or strategic level), and affective.

So how is that article useful when thinking about the kinds of games I am interested in, e.g. the Biodiversity Collage or the Climate Fresk?

Looking at the characteristics of successful games, at least on the surface, the Biodiversity Collage does not seem to be a good match. There isn’t a lot of fantasy world going on, and no “sensory stimuli”. But on the other hand, even though the topic is very much about the real world, what happens in the game does not have any real-life impact, so it is a safe test bed to think and talk about complex relationships, and trying out new technical terminology. At the same time, it is challenging, complex, and players have a fair amount of control in how they want to do things.

Inside the game cycle, a lot then depends on the facilitator and their feedback. In the workshops I have attended, this part was really well done: The goal changed a bit over time with more and more cards being dealt, but it always seemed aaaaalmost achievable, and the feedback was always encouraging and motivating. In the facilitator training I have been part of, this was very well instructed, too, but in the end it probably depends on how good the facilitator is in their role.

Lastly, the debriefing phase, and the learning outcomes that are realistically achievable. Here I see a lot of room for improvement in what I have observed both in the workshops and the training I have attended, but the article doesn’t really give good guidance on how this should be done. But I’ll stay on it!

Garris, R., Ahlers, R., & Driskell, J. E. (2002). Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simulation & gaming, 33(4), 441-467.