“Excursion week” in Oceanography 101 while physically distancing

My friend’s university recently decided that “excursion week” (a week in May during which there are no lectures or exercises or anything happening at university to make time for field courses during the semester) is cancelled this year. Which is, of course, not surprising given the current situation, but it isn’t cancelled as in “go have a week of vacation”, it’s cancelled as in “one more week of lectures”. Which is putting even more of a burden on people who are already struggling to provide students with the best teaching they can in a new, online setting. To help my friend out (as well as anybody else who might be teaching intro to oceanography classes right now), I’ve collected a couple of ideas of how to fill this week in a way that’s keeping at least a bit of the spirit of exploration alive.

Learning about concepts, observations, experimentation

Of course I can’t give you a solution that perfectly replaces a field course by something that isn’t a fieldcourse. But that doesn’t mean that many of the learning outcomes usually associated with field courses can’t be had in non-fieldcourse settings.

What are the learning outcomes that you care about most? Understanding of specific concepts? Then maybe those concepts, even though most impressively seen at the location where you typically go for your field course, can be observed in other places, too, if students are guided to find them. Or learning to observe following a specific protocol? Then maybe this protocol can be followed (or mostly followed) while collecting a different type of data than it is usually used on. Here are a couple of suggestions of ways to do this:

A: Field course at home

There are two different scenarios that I think can work well here: Having students explore the world right outside their home with a focus on topics from their course, or having them explore the enormous amount of available datasets on the internet.

A.1: Exploring the neighbourhood

Assuming students are able to walk around outside their homes (as they currently are where I’m at), having them explore the neighbourhood. There are different kinds of tasks that could work depending on your learning outcomes:

A.1.1: Find examples of specific science concepts

The tasks can be very specific (“find examples of hydraulic jumps“, “observe tidal flows in a river by watching moored structures move“) or not so specific (“pick a topic related to our class and find a way to observe it”). I think this is a really nice task because it helps students discover how prevalent the concepts are in their daily lives, rather than being something that only exists in books and lectures and really far-away locations that field courses would go to. Careful, as you see with my wave watching, this can get addictive!

A.1.2: Explain something you know for sure they will be able to observe

If you know where your students currently are, you can also ask them to observe specific features and explain them (“Make a time series of positions of that moored structure in the tidal river and relate the positions to the tidal cycle“, or for tons of ideas in Bergen see #BergenWaveWatching on Elin’s blog). This is also a really nice task, again because it brings concepts from the lecture into students’ real lives. It’s also maybe a little easier to relate to the rest of your course since you have a better idea of what they will be observing and interpreting.

A.2: Exploring the interwebs

This is just a quick side note, but of course there are TONS of data available on the internet. From observations of salinity, temperature, pressure mounted on seals in Antarctica, to winds and waves observed from satellites. Many of them even come with interfaces ready to do easy plots. And I’ve been a big fan of the lovely people on Twitter (shoutout to @aida_alvera and @remi_wnd particularly, I always love your posts!) that post interesting features from recent satellite images. So much to discover! Trying that for myself has been on my to do list for quite a while. You’d think I would find time for it during Corona isolation, wouldn’t you?

A.3: Ask others for observations that students can work with

Kinda like what I do with #friendlywaves where people send me pictures of waves and I try to explain the physics I see (while dreaming that it’s me on that ship in Lofoten…). This would be so much fun if students took pictures of interesting features they saw (or went through their old pics) and then shared them and asked each other for ideas what might have happened there. Or if you asked people to take pictures for you, or accessed webcams (like this one, looking at Saltstraumen, the strongest tidal current!), took screenshots and analysed those. I’d totally be in!

[Edit 13.5.2020: Here is a cool example of a virtual field course that was done at UNIS, using videos of field sites and discussing them in groups]

B: Kitchen Oceanography

Of course, #KitchenOceanography is my solution to everything. Need to make a class more interesting? Bring some #KitchenOceanography to the classroom! Can’t teach in-person classes but want people to still have hands-on experiences? Let them do #KitchenOceanography at home! Feel down in isolation and need something to cheer you up? Do some #KitchenOceanography!

So here are a couple of ways to have students do #KitchenOceanography while physically distancing.

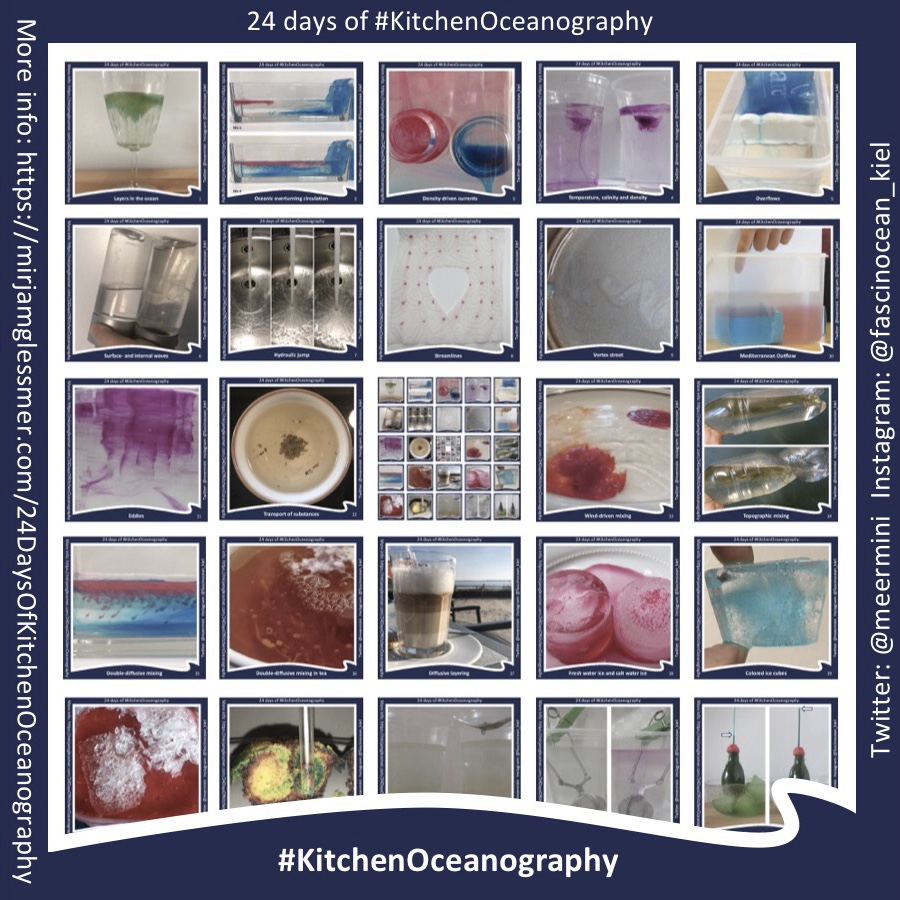

B.1: Following my 24 days of #KitchenOceanography

If you haven’t seen my 24 days of #KitchenOceanography yet, you might want to check it out. If you want to give your students a recipe for kitchen oceanography, there is probably something in there that works with your Oceanography 101 class! You could ask them to do one experiment that you find most relevant to your class, or pick one they find most interesting, or distribute all 24 experiments over all the students and have them report back.

And even though I’m so depriciatingly talking about “recipes” and structured activities, be assured that for most students things won’t end after they’ve done the experiment. There is ALWAYS something they observe that they still want to figure out, so there will be more experimentation going on than you expect!

B.2: Problem solving

This is a little more difficult to do if you and your students only communicate electronically and you can’t give them physical samples to investigate (but if you can place samples somewhere where students can easily and safely pick them up, you could for example give them salt water samples and ask them to figure out the sample’s salinity, or give them a fresh water and a salt water sample and ask them to figure out which one is which only using ice cubes). But there are still tons of ways problem solving can be practiced, for example by asking students to figure out ways to measure temperature, salinity and density.

B.3: Open-ended investigation

This is the most fun way to do kitchen oceanography, but depending on whether students have ever done these kinds of experiments before or not, it might be worth starting with a more guided kitchen oceanography experiment. But ultimately, this is where you ask students to figure things out in their kitchens. Currently on the list of things I want to try when I get the time (again, how is Corona isolation not the time for this kind of stuff? But somehow it isn’t): Can I actually see a change in the refraction of a spoon in a glass of very cold salt water as compared to warm fresh water? How big is that density effect? Would I be able to see the spoon bend where it goes through a density stratification in my glass? I bet you, once I start playing with this, that’s that for that evening!

C: Bonus idea: Ocean podcasts & books

There are two oceanography-themed podcasts that I really enjoy listening to (and I’m not a podcast person!): Climate Scientists and Treibholz. Both would be great to listen to interviews with super cool scientists while dreaming yourself away to expeditions to the Arctic or Antarctica. There is so much to learn from other people’s experiences in the field — why not ask students to listen to other people’s experiences with a focus on either the science, or the methods, or anything else?

And of course there are tons of books that would lend themselves to that, too, for example xplorer’s diaries. Nansen’s “Farthest North” (1897) for example fits super well if you wanted to talk about the discovery of dead water…

Bringing it all together

The big question is: Once your students have done the tasks of finding/producing and describing phenomena, what do they do with that? It might not come as a surprise, but I think that they should be encouraged to publicly share them on the internet. Both because it’s a good opportunity for them to build their scicomm profile, but also because there are surpisingly many people who get really excited about (read here how Prof. Tessa M Hill‘s student Robert Dellinger posted a video of an overturning circulation on his 70-ish follower Twitter account, and the video has, as of April 16th, 70 retweets and 309 likes!) and that’s such a motivating feedback for them!

Of course, the sharing and excited reactions could also happen within your university’s learning management system, but honestly … no. Ask them to share it via social media! I, for one, am definitely more than happy to comment and ask questions and share my excitement there! :-)