Stuff you can (and should!) observe in your kitchen: circulation in the water when boiling eggs

Now that I have introduced the new tag “kitchen oceanography: food related” to my blog, it’s time to add a couple new posts to that category. And today I have a fun post for you!

But first, what does “kitchen oceanography” even mean?

Kitchen oceanography

The benefits of “kitchen oceanography”

It’s pretty apparent why “kitchen oceanography” is a great alternative to regular tank experiments: because you can do it with stuff you have at home rather than needing access to a lab with a tank, and then a lot of water, salt, dye, other resources to conduct the experiments. Doing kitchen oceanography, we use a minimal amount of resources.

But the second, even larger benefit to me is that you can do these kinds of experiments and observations basically everywhere and at any time. So you can fit in a quick session of kitchen oceanography while sitting in front of the fire place on a skiing trip with friends, or while doing the dishes with your godchild. And you can inspire others who might not have access to labs to still do cool oceanography experiments, at home or wherever they like!

Kids who have cooked with their parents are more likely to be interested in STEM

Apparently, the biggest predictor of future interest in STEM topics is whether people as kids often cooked with their parents! No literature source for this, but that’s what my educational research colleagues next door told me… So playing in the kitchen, whether on kitchen oceanography or with food, is a good thing!

It’s not like watching paint dry: Observing boiling eggs

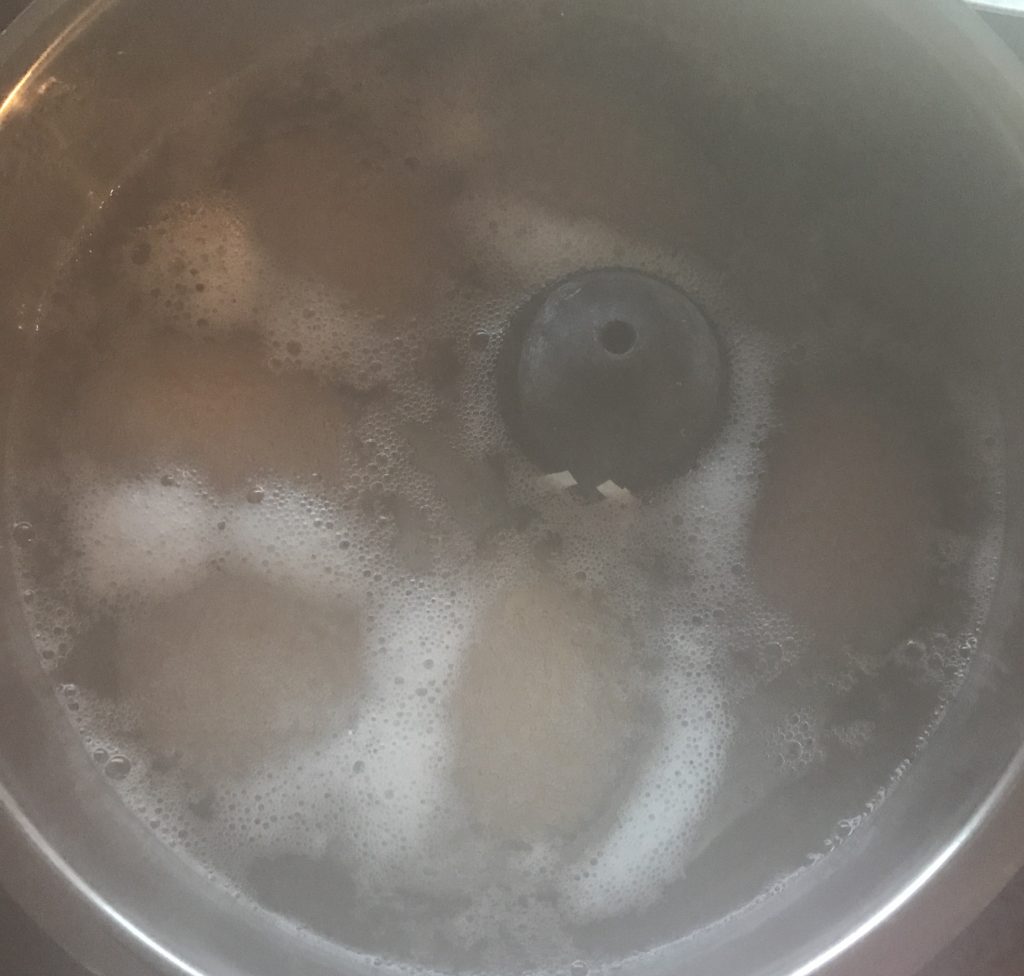

Observing boiling eggs might not sound like a super exciting activity to engage in, but sometimes it is. Last year we did observe interesting foam pattern when boiling eggs (I still can’t explain where the foam is coming from! Can you?).

Foam pattern in a pot of boiling eggs. P.S.: The “black egg” sings different songs to let me know how hard-boiled my eggs are at any given moment. I love this because they are songs I learned from my godson and it always reminds me of him and his family :-)

Foam pattern show circulation within the pot

The pattern in the foam show the convection pattern of the boiling water around the eggs which act as obstacles. Water is raising from the bottom of the pot to its surface, bringing up foam. But the eggs are located so close below the water’s surface that the circulation above them (if there is one) is pretty much disconnected from the convection happening all around the eggs.

But then if you throw out the water…

Even the empty pot still shows you what the circulation pattern must have been like!

But then the next cool thing happens when you throw out the water: There are limescale crystals on the bottom of the pot! And, interestingly enough, they show the former locations of the eggs. And I think they are forming in exactly those spots because just as there is (hardly any) circulation above the eggs, the circulation below is also inhibited, water has longer residence time (because it isn’t whipped away by convection) and those crystals can form.

An alternative explanation might be that there is more limescale below the eggs because calcium carbonate gets dissolved from the egg shells and gets deposited as limescale right below the eggs because the concentration is highest closes to the eggs.

Which explanation do you think is more likely? Or do you have another one entirely?