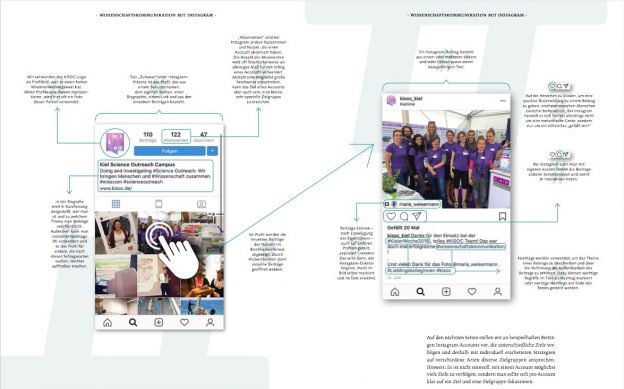

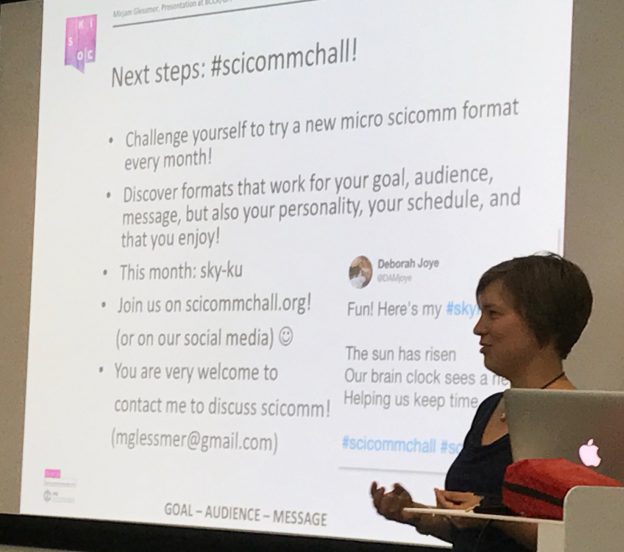

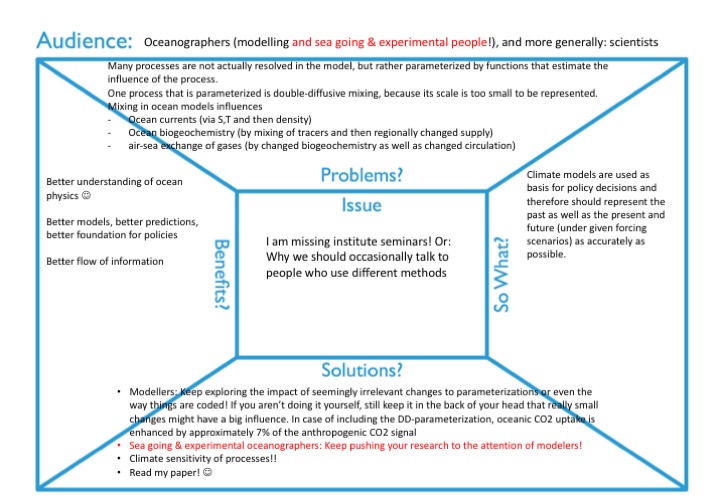

In a presentation about science communication I gave on Monday, I recommended a couple of resources for scientists interested in science communication. For example the amazing climatevisuals.org for advice on which images to use to communicate about climate change (plus lots of images that even come with explanations for what purpose they work well, and why!). And of course my #scicommchall to get people inspired to try out a new micro scicomm format every month.

But here is an (open access!) book I wish I had known about then already but only came across two days after my presentation: “Communicating Climate Change” by A. K. Armstrong, M. E. Krasny, J. P. Schuldt (2018).

This is a book aimed at educators who want to communicate climate change in a literature-based and effective manner. It consists of four parts: A background, the psychology of climate change, communication, and stories from the field, which I will briefly review below (and you should definitely check out the real thing!). It’s nice and easy to read, and there are “bottom line for educators” at the end of each chapter as well as recaps at the end of each part, making it easy to get a quick overview even if you might not have the time to read the whole thing in detail.

Background

This part of the book begins with an introduction to climate change science, reporting state-of-the-art science on climate, greenhouse gases, evidence for climate change, and climate impacts. It then moves to how climate change can be addressed: by mitigating or adapting to its effects, how it is important to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and how that can be achieved both on an individual level and by collective action. It ends with a “bottom line for educators” summary that stresses that climate change is real, that misinformation campaigns are an unfortunate reality, and that educators can contribute to solving the problem.

The next chapter then deals with what is known on attitudes and knowledge about climate change in different audiences internationally and at different ages, explaining that attitudes are actually a pretty bad predictor for behaviour, but nevertheless important to know about if you are an educator! For example, if you want teens to be concerned about climate change, a useful approach might be to involve their parents along with them, since what family and friends believe about climate change is very important to what an individual teenager believes, as is how often they discuss climate topics with their friends and family. Again, the “bottom line for educators” breaks this down into advice, for example to focus on different topics depending on how concerned about climate change a given audience already is, or to focus on areas in which a common ground between them and their audiences exists in order to generate a constructive and positive dialogue even though there might still be areas in which they do not agree with their audiences (which they should think about beforehand, hence the importance to know about the audience’s attitudes).

The next chapter suggests possible outcomes for climate change education — how do we know if a climate change communication activity was successful? — and stresses the importance of defining these goals in the first place. Outcomes can be defined on the level of individuals, of communities, of the environment, or of resilience of all of the above. For individuals, outcomes could for example be literacy (understanding essential principles, knowledge of how to assess scientifically credible information, ability to communicate, ability to make informed and responsible decisions) of climate change, or attitudes and emotions, the feeling of confidence that you can reach your goals, or environmentally friendly behaviour. For communities, outcomes could be positive development of youth, building of social capital (e.g. trust or positive action), the belief that the community can reach a goal together, or action taken together by the whole community. Focussing on the environment, an outcome could be adaptation to, or mitigation of, climate change.

The next chapter then presents three climate change vignettes — three examples of how different educators address different audiences in different settings — and a discussion of why they chose to design their activity a certain way and react to questions or comments the way they did.

The psychology of climate change

This part of the book presents psychology research on why knowledge about climate change is not sufficient to actually change behaviours.

Identity research especially is very helpful, as it explains how in order to feel like you are part of a group (something that we as humans are hard-wired to crave) we tend to conform with our group’s norms and values. We might be part of different groups at different times as well as simultaneously (for example our family as one and our colleagues as another, or inhabitant of a city, or student of oceanography), and contexts trigger specific identities that might even not be completely congruent with each other. When new information is presented, we interpret it in a way that does not threaten our identity in the context the information is presented in. Therefore, in order to not threaten anybody’s identity and making it impossible for them to take on our message, it is important to make sure that climate change is not communicated as something polarising or political, but rather choose to trigger identities that are inclusive, like for example “inhabitant of place x”, and focus on outcomes that benefit that community independent of what other identities might exist, by for example protecting a local beach.

Psychological distance is another lens through which climate change communication can be viewed. The more distant a problem seems, the less important it is perceived. Therefore focussing on local relevance rather than global, on places that are important to people, on communities they care about, might in some cases be helpful — although not always; the results of the research on this are not conclusive yet.

Then a few other relevant psychological research areas are discussed, like for example “terror management theory”. This leads to the recommendation to avoid “doom and gloom” presentations of climate change that might kick people into a defence mechanism of ignoring the topic to protect their emotional well-being in the moment, and to focus on hope and positive action instead. Then there is the “cognitive dissonance theory”, according to which we try to ignore information that conflicts with what we think we already know or threatens other goals we might have. The recommendation here is to give people ideas of easy things they can do to combat climate change to combat cognitive dissonance.

Communication

This part of the book presents three aspects of communicating climate change: How we frame it, which analogies and metaphors we use, and how we, as a messenger, can build trust.

“Framing” is about how a message is featured in a story line to help the audience interpret it in a certain way, by making certain aspects of it especially visible, for example economic aspects or tipping points. When thinking about framing a climate change message, it is important to think about audiences and their identities and to avoid wording that will trigger identities which make it difficult to accept the message. Depending on the desired outcomes, climate change communications could, for example, be framed for solutions, hope, or values. There are ways to build entire climate change communication programs around those frames, and there are several examples given for how this might be done.

The next chapter focusses on analogies and metaphors. For example, “osteoporosis of the sea” (which I had never heard in use before) has been found to be a successful metaphor for ocean acidification. However, as all metaphors, it only highlights similarities between issues and neglects to mention the dissimilarities which makes them tricky to use because it’s hard to make sure people don’t take a metaphor so far that it breaks down. In fact, to address this problem, the authors recommend to explicitly talk about where the analogy or metaphor will break down.

Establishing trust in the climate change messengers: This is tricky as people tend to trust other people that hold values similar to their own. Therefore it is helpful to think about the messenger and to use trusted middle persons. [There is are actually some very interesting work on trust out there, for example by Hendriks, Kienhues and Bromme (2015) that isn’t mentioned in the book, but that I’d be happy to summarise for you if anyone is interested!]

Stories from the field

The book ends with a part called “stories from the field” in which examples of different climate change communication activities, focussing on different goals, audiences, messenges and happening in very different settings, are given and the design choices that were made explained in detail. Also for each of the story, an example is given how the message is phrased in actual interaction with the target audience. All of this is super interesting to read because all the theory the book provided in the previous chapters is applied to real world cases, which makes it easy to see how they might be applied to your own climate change communication activities. Also these best practice examples are inspiring to see and give me a sense of hope.

To sum up: I really enjoyed reading this book! So much so that continuing reading it was more important than getting a good Instagram pic of my latte while writing this blogpost. I would really recommend anyone interested in climate change communication to check it out! When I finished my talk on Monday, on my second to last slide I put the African proverb along the lines of “if you think you are too small to make a difference, try going to sleep with a mosquito in the room”. I used this to talk about using messages of hope in climate change communication, and then also applied it to science communication — don’t think you are too small to make a difference there, either! And that’s a message that this book conveys really well, too, providing a good idea of what one could do and how one might go about it, and inspiring one — or at least me — to do so, too.