Tag: salt fingering

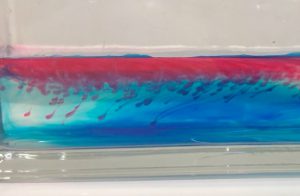

Salt fingers in my overturning experiment

You might have noticed them in yesterday’s thermally driven overturning video: salt fingers! In the image below you see them developing in the far left: Little red dye plumes moving…

Experiment: Double-diffusive mixing (salt fingering)

On the coolest process in oceanography. My favorite oceanographic process, as all of my students and many of my acquaintances know, is double-diffusive mixing. Look at how awesome it is:…

Experiment: Temperature-driven circulation

My favorite experiment. Quick and easy and very impressive way to illustrate the influence of temperature on water densities. This experiment is great if you want to talk about temperature…

My favorite demonstration of the coolest mixing process: Salt fingering!

I am updating many of my old posts on experiments and combining multiple posts on the same topic to come up with a state-of-the-art post, so you can always find the…

Salt fingering

How to show my favorite oceanographic process in class, and why. As I mentioned in this post, I have used double-diffusive mixing extensively in my teaching. For several reasons: Firstly,…