One thing I really enjoy about teaching virtually is that it is really easy to address everybody by their names with confidence, since their names are always right there, right below their faces. But that really does not have to end once we are back in lecture theatres again, because even in large classes, we can always build and use name tents. And voilà: names are there again, right underneath people’s faces!

Sounds a bit silly when there are dozens or hundreds of students in the lecture theatre, both because it has a kindergarten feel and also because there are so many names, some of them too far away to read from the front, and also you can’t possibly address this many students by name anyway? In last week’s CHESS/iEarth workshop, run by Cathy and Mattias on “students as partners”, we touched upon the topic of the importance of knowing students’ names, and that reminded me of an article that I’ve been wanting to write about forever, that actually gives a lot of good reasons for using name tents: “What’s in a name? The importance of students perceiving that an instructor knows their names in a high-enrollment biology classroom” by Cooper et al. (2017). So here we go!

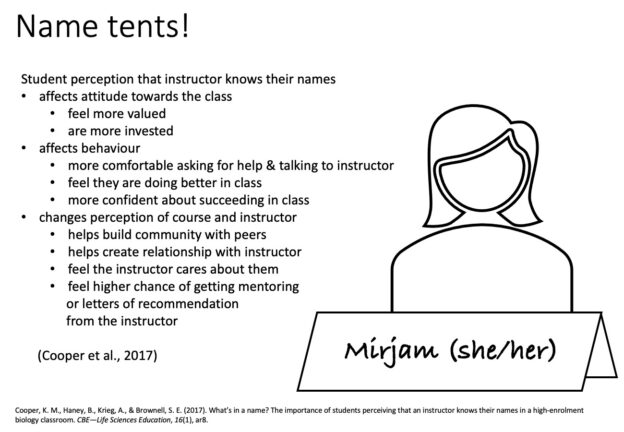

In that biology class with 185 students, the instructors encouraged the regular use of name tents (those folded pieces of paper that students put up in front of themselves), and afterwards the impact of those was investigated. What they found is that while of the large classes students had taken previously, only 20% of the students thought that instructors knew their names. In this class it were actually 78% (even though in reality, instructors knew only 53% of the names). And 85% of students felt that instructors knowing their names was important. It is important for nine different reasons that can be classified under three categories, as Cooper and colleagues found out:

- When students think the instructor knows their names, it affects their attitude towards the class since they feel more valued and also more invested.

- Students then also behave differently, because they feel more comfortable asking for help and talking to the instructor in general. They also feel like they are doing better in the class and are more confident about succeeding in class.

- It also changes how they perceive the course and the instructor: In the course, it helps them build a community with their peers. They also feel that it helps create relationships between them and the instructor, and that the instructor cares about them, and that the chance of getting mentoring or letters of recommendation from the instructor is increased.

So what does that mean for us as instructors? I agree with the authors that this is a “low-effort, high-impact” practice. Paper tents cost next to nothing and they don’t require any effort to prepare on the instructor’s side (other than it might be helpful to supply some paper). Using them is as simple as asking students to make them, and then regularly reminding them to put them up again (in the class described in the article, this happened both verbally as well as on the first slide of the presentation). Obviously, we then also need to make use of the name tents and actually call students by their names, and not only the ones in the first row, but also the ones further in the back (and walking through a classroom — both while presenting as well as when students are working in small groups or on their own, as for example in a think-pair-share setting — is a good strategy in any case because it breaks up things and gives more students direct access to the instructor). And in the end, students even sometimes felt that the instructors knew their names when they, in fact, did not, so we don’t actually have to know all the names for positive effects to occur (but I wonder what happens if students switch name tents for fun and the instructor does not notice. Is that going to just affect the two that switched, or more people since the illusion has been blown).

In any case, I will definitely be using name tents next time I’m actually in the same physical space as other people. How about you? (Also, don’t forget to include pronouns! Read Laura Guertin’s blogpost on why)

Cooper, K. M., Haney, B., Krieg, A., & Brownell, S. E. (2017). What’s in a name? The importance of students perceiving that an instructor knows their names in a high-enrollment biology classroom. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(1), ar8.