Currently reading Williams & Grain (2025) on “Teaching in a Time of Climate Collapse: From “An Education in Hope” to a Praxis of Critical Hope”

“Sustainability educators face a conundrum in the midst of climate collapse: what if to teach truthfully is to break hearts? What if teaching with the most current and rigorous research is tantamount to inducing hopelessness, anger, and anxiety?” This is the introduction to Williams and Grain (2025)’s article “Teaching in a Time of Climate Collapse: From “An Education in Hope” to a Praxis of Critical Hope“.

They ask “What is the job of a sustainability educator at this point in the climate crisis? What good is hope if the object of hopefulness is not achievable?” and argue that rather than just teaching the same old course curriculum as always, “the job of a sustainability educator has, by necessity, grown and transformed to becoming an educator in the praxis of critical hope“. I have written about different conceptions of hope before, but for critical hope (as “a politically conscious, action-driven practice that resists passive optimism“) specifically, in addition to core sustainability concepts, educators need to teach

- how to cope with emotions (see several posts here on strategies to cope with climate anxiety and to foster active hope),

- how to recognise injustices embedded in complex systems, and

- how to organise action for equity and justice (or transgression, as my colleagues recently argued).

Then, Williams and Grain (2025) present how they work with critical hope in a course on “wicked problems“. Early on in the course, students wrote an essay about hope and the climate crisis, with all students describing feelings of hopelessness. They were then asked to, for the duration of the semester, work on their mental health coping skills (through meditation, physical activity, art, music, time outside, …) and to get involved in environmental action (volunteering for at least 8 hours over the course of the semester), and had weekly check-ins and reflections on their activities. In parallel to that, they worked on their wicked problems, systems thinking, and among others questions of privilege, applied to concrete situations on their campus. In reflections at the end of the course, students show a changed understanding of hope.

Based on these experiences, Williams and Grain (2025) propose “key takeaways for sustainability educators to emphasize when guiding students through a praxis of critical hope“:

- “Strong emotions are a reasonable response to the climate crisis“, and teachers need to create opportunities for students to engage with those emotions, both inside and outside of the classroom

- “Different emotions can be co-conspirators for prompting action” — emotions like anger and grief can be activating, and they can co-exist with others like hope and joy

- “Emotional responses and climate action approaches are power-laden, diverse, and identity-related“, and the classroom should provide a space to discuss this and integrate new ideas into students’ identities

- “Consciousness raising and systems thinking are complimentary approaches“. You need to collect the dots to connect the dots, so students need to become aware of injustices before they can address them

- “Localizing systemic issues empowers students to situate and leverage climate emotions“. Local entry points might make it easier for students to identify with and care about global issues

But some questions remain open, as highlighted by the authors, for example can transformation be achieved also when critical hope isn’t as central for as long a duration as the course presented above? And which facets of critical hope are most crucial to address? How can critical hope be integrated into existing courses? How long does the impact of the course presented here even persist?

What I really appreciate about this article is how the “principles of critical hope” become much more concrete through the case study. They are initially stated as cited here:

1. Hope is necessary, but hope alone is not enough.

2. Critical hope is not something you have; it is something you practice.

3. Critical hope is messy, uncomfortable, and full of contradictions.

4. Critical hope is intimately entangled with the body and the land.

5. Critical hope requires bearing witness to social and historical trauma.

6. Critical hope requires interruptions and invitations.

7. Anger and grief have a seat at the table.

But applied to the case study, it becomes clear what they can mean in practice and how they can actually serve as a framework for teaching.

A bit similar to the open questions the authors point out, I am wondering if critical hope could be used as a framework, but “fly under the radar” for a bit, so that discussions about whether a teacher should be dealing with hope and emotions can be postponed until there is a pilot, or even proof of concept, in place? It feels like many, if not all, of the principles of critical hope can be addressed without explicitly linking them to critical hope. For example along these lines

- “Hope is necessary, but hope alone is not enough.” This is pretty clear from the historical evidence, and should really not be a problem to point out when teaching anything related to sustainability or climate change (and of course we can also plan to make this point in exactly that context)

- “Critical hope is not something you have; it is something you practice.” Here, maybe the practice can come before the commitment (as intentions are a bad predictor for future actions anyway), and before disclosing to students why we are doing something, so that they can reflect on the effect of a practice later. In their case, Williams & Grain (2025) use the semester-long mental health care and activism tasks, but maybe this can be scaled down to in-class mental health practices as a first step

- “Critical hope is messy, uncomfortable, and full of contradictions.” I would assume that there will be situations naturally coming up (or easily planned in, especially for the contradictions) where this point can be made

- “Critical hope is intimately entangled with the body and the land.” A common recommendation for sustainability teaching is to use place-based methods and embodied learning, so this might even already be addressed in a course

- “Critical hope requires bearing witness to social and historical trauma.” I think this is the most difficult point in my specific context, where we do not tend to talk about trauma at all, and definitely not trauma that was caused a long time ago or far away, but may still be reproduced or have effects here and now. But maybe this is where teachers just need to role-model talking about things. After all, they set the tone for what students believe should be discussed in a course

- “Critical hope requires interruptions and invitations.” Following on the previous point — sometimes we need to disrupt what students believe happens in a classroom, or interrupt the flow of things they are used to, in order to invite them into conversations that matter, into imagining something new

- “Anger and grief have a seat at the table.” I tend to fall back on Ruth Cohn’s “Störungen haben Vorrang”/”Disruption takes precedence” — if there is something going on in the group (or even just an individual), that needs to be taken up and addressed before the regular scheduled teaching can continue; it would anyway take up most of the attention if ignored… So that is the same here when emotions come up for students. Especially when there are interruptions, or students feeling uneasy with what is happening in class, this needs to be taken up and students need to be invited into conversations

Maybe this is not ambitious enough, maybe we should go all-in right away? Or maybe that’s a good strategy, maybe these are first steps that we can take to feel forward into the right direction, and then once we’ve tried it, we can be a bit bolder next time?

Williams, R. J., & Grain, K. (2025). Teaching in a Time of Climate Collapse: From “An Education in Hope” to a Praxis of Critical Hope. Sustainability, 17 (12), 5459.

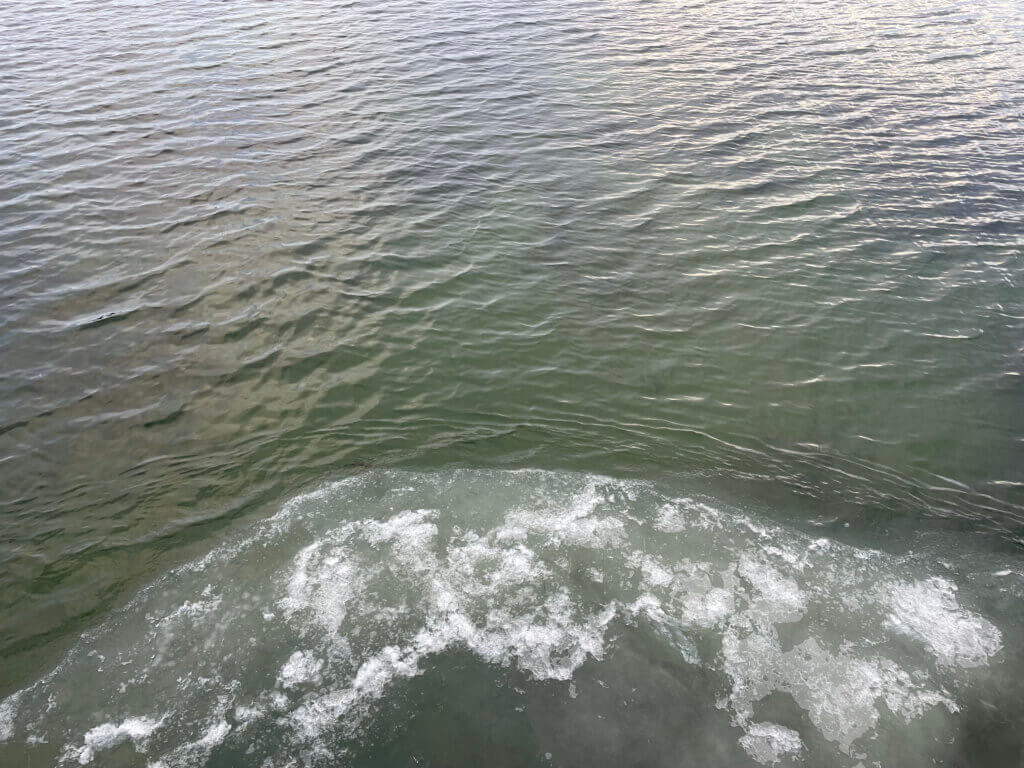

Interesting ice and wave watching yesterday! There was a lot of ice floating around, some of it accumulating under the platform.

Maybe not the most comfortable spot to go dipping…

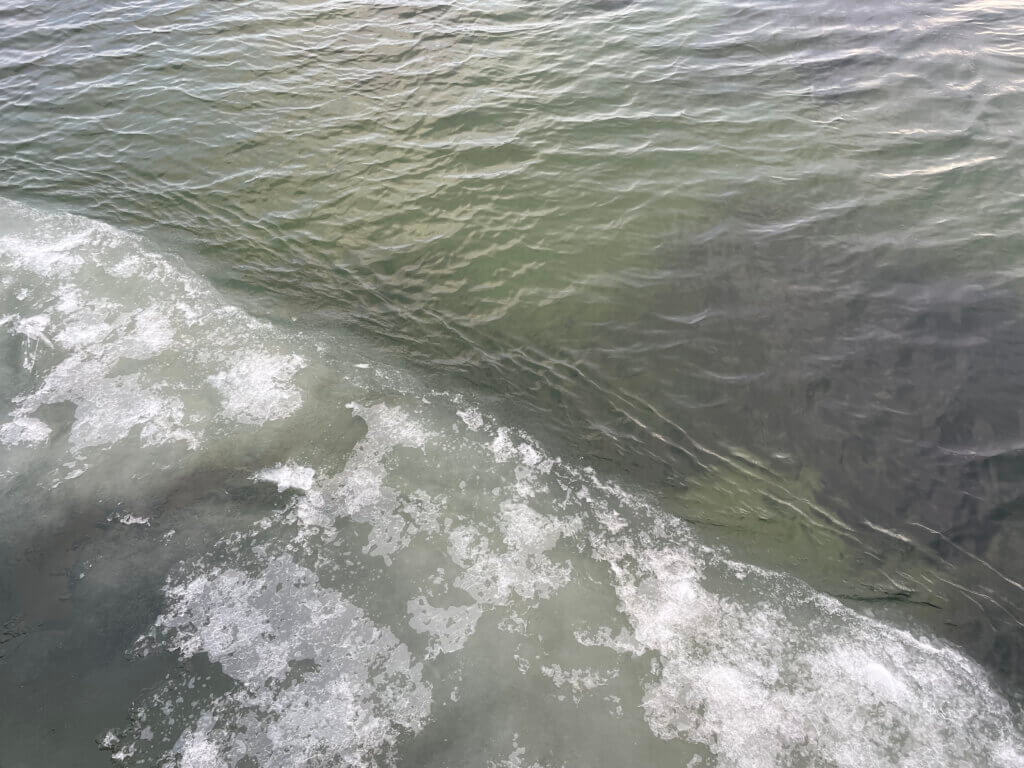

But it is really interesting how a thin layer of ice, floating on the surface, can influence the surface current! See the band of current along the ice edge?

I thought that was really impressive; usually you would only see waves getting reflected, but here they seem to get flushed away with the current!

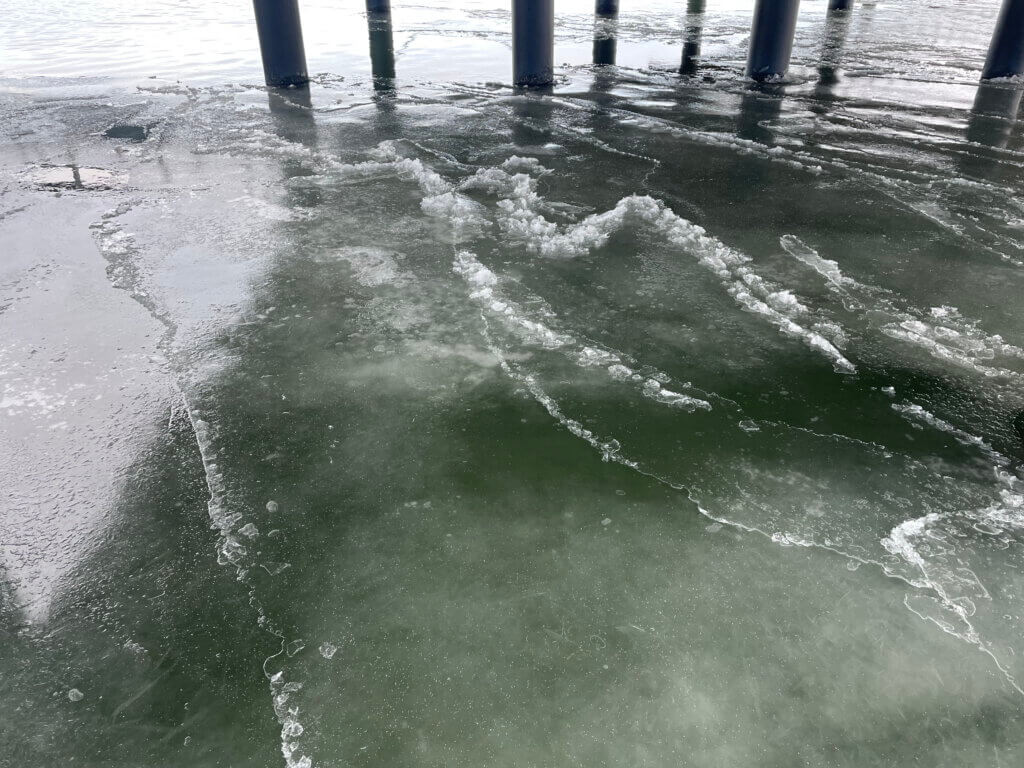

The ice under the platform showed ice finger rafting, but it was surprisingly difficult to capture that on a picture…