Now published: Forsyth & Glessmer (2025) on “How teachers build trust with students in the presence of GenAI”

Rachel Forsyth and I are in the process of doing focus group interviews with students and teachers at Lund University on how their relationships to each other are influenced by the availability of GenAI. We are going to present a glimpse into the analysis of what teachers said in the first five interviews at LTH’s pedagogical inspiration conference in December, but the proceedings are out now already! You find the official pdf here, or can read the same thing below.

Abstract — Trust is a prerequisite for successful learning. From previous work we know that teachers use multiple strategies to build trust with students – for example to demonstrate knowledge, skill and competence, or showing interpersonal care and concern. We also know from students that they trust teachers who ask, listen, and respond. But since we conducted those studies, Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools have become universally available and are now used by students and teachers. Although both groups are well aware that GenAI is likely used both within their own and in the other group, there are only few conversations between teachers and students where either talk transparently and in detail about how they use GenAI. We suspect that the presence of GenAI – fuelled by a lack of conversations about use – influences trust in the relationship between teachers and students.

We conducted focus group interviews with teachers at LU to hear about their experience with and perspective on GenAI usage, both their own and their students’, and to understand the impact that they think the presence of GenAI has on their relationships with students. We find that teachers generally think a lot about GenAI and their influence on teaching and assessment practices but are often unsure what to do about them.

I. INTRODUCTION

Relationships are essential for learning, and trust is essential for relationships (Felten & Lambert, 2020). We give a brief overview over the literature on trust in higher education relationships pre- and post GenAI.

A. Trust pre-GenAI

Recent research has considered the role of teachers in building trust (Felten et al., 2023), why teachers might mistrust students (Macfarlane, 2022), students’ perceptions of what makes them trust teachers (Glessmer et al., 2025), and a variety of ways to conceptualise the importance and construction of trust in teaching and learning (Zhou, 2023). This is an emerging field, but the ways in which teachers talk about their trust-building, such as “Trust me”, “I trust you” (Sutherland et al., 2024, p 5), suggest perceptions of trust and trust-building approaches that could be easily damaged by the wide availability of GenAI tools.

B. Trust in the present of GenAI

Since the release of the Large Language Model ChatGPT in November 2022, there is an emerging field of research on trust related to GenAI in a teaching and learning context. But so far, most of it focusses on whether a) GenAI can be trusted to do various tasks correctly (Bašić et al., 2023), b) students and/or teachers trust GenAI outputs to produce correct results (Zhai et al., 2024), c) students cheat more now (Farazouli et al., 2023). Our own research shows that students feel that there are too few conversations about how to use GenAI between them and teachers, and that they want teachers to talk about GenAI, explain rules around what does and does not count as cheating, and how GenAI can be used for their learning of the subject and for future work in the discipline (Loft, 2025).

Here, however, we are primarily interested in the social outcomes: How does the presence of GenAI influence relationships, and specifically trust, between teachers and students? In this article, we will focus on one specific aspect of this question: What do teachers report they do – in the presence of GenAI – to build trust with students?

II. Methods

To investigate this question, we ran five focus groups in late summer of 2025 with a total of 17 teachers from seven faculties at LU, of which six were from LTH. Five students also participated in these focus groups, but their comments are not reported here. Opportunistic sampling was used: pre-existing personal connections of the authors were approached and asked to join. Some further participants were recruited using snowballing methods.

RF led the discussions in the focus groups, while MSG monitored the process and took notes. Focus groups were run as semi-structured interviews, where participants were first prompted to think about trust and GenAI separately, and then asked how they thought the presence of GenAI influenced trust, and what they did to build trust. The following results and recommendations stem from these parts of the sessions.

III. Results

During the focus group interviews, it was very clear that trust is a topic that teachers think about a lot, not just between themselves and students, but also with peers, or between students, or even trust in their own competence and skills.

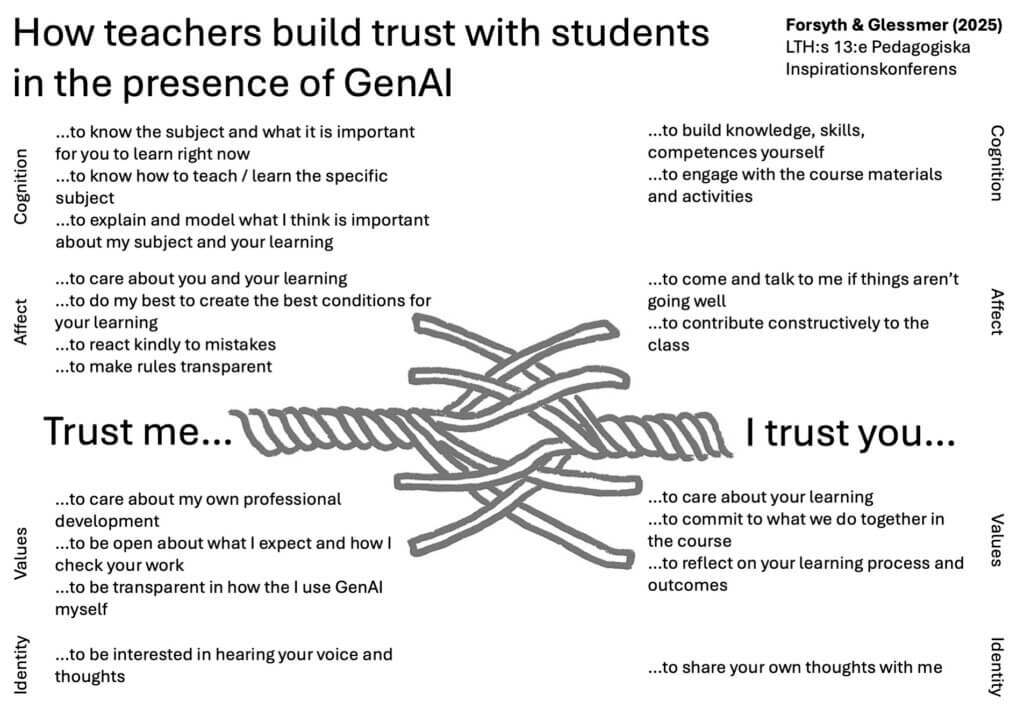

For the purpose of this article, we focus here on summarizing the main trust messages that teachers reported using, which we have mapped in Figure 1 to the expressions of trust identified by Sutherland et al (2024) (“Trust me” and “I trust you”) and Felten et al. (2023)’s categories: Cognition (showing knowledge, skills, competences), affect (showing interpersonal care and concern), identity (showing sensitivity to their own and/or others’ identities), and values (showing that they are acting on principle). These “moves”, to use Felten et al. (2023)’s terminology, might be useful to other teachers to consider using when they want to talk about trust with their students but don’t quite know where to start, in order to express both their own trustworthiness as well as their trust into students.

1. “Trust me!”

The main group of messages that teachers report using to build trust with students are about conveying their own trustworthiness to students: “Trust me!” messages. Examples include “You don’t need to rely on GenAI, trust me to know how learning and teaching in the subject works”, “I will show you examples of the work created without and with GenAI so you can learn to understand what GenAI can and cannot do” or “Trust me to model what I think is important about my subject and your learning, including how to use GenAI in the subject” (cognition); “Trust me to care about you and your learning, and that my teaching is designed to support the process”, “trust me to not ‘dumförklara’, to not talk down on you” (affect); “Trust me to be transparent in how I use GenAI myself, both in producing teaching materials and in assessing your work” (values), “Developing your own voice and making mistakes along the way is a key part of higher education. Trust me that I want to hear what you have to say, in your own voice” (identity).

2. “I trust you!”

A second, very important, group of trust messages that teachers report using are “I trust you!” messages, which often had a strong undertone of “and you should trust yourself, too!”, as well as a lot of compassion for students. We teachers remember a time before and after GenAI. We know how to find information, how to learn, how to proofread a text and decide that it is good enough to be submitted, without GenAI, but students increasingly do not. Therefore, students need to learn how learning works without GenAI, about what GenAI can and cannot do. We need to help students build self-efficacy and trust in their own capabilities so they don’t feel the need to rely on GenAI to create a product that will meet the teacher’s expectations.

Examples of expressions of teacher trust in students are “I trust you to engage with the course material and to be able to build knowledge, skills, competence” (cognition), “I trust you to let me know when you need help”, “I trust you to ask me questions when something is unclear” (affect), “There were always ways to cheat, like asking a parent or paying someone else, and I trust that you don’t do that because I trust that you are here in order to learn” (values), and “I trust you to not hide behind GenAI but to share your own thoughts with me” (identity).

Figure 1: Trust moves that teachers reported on in our focus group interviews

IV. Conclusions

We have presented moves that teachers report on using to build trust with students in the presence of GenAI. It is important to stress that the intention behind sharing the trust moves is to help teachers express their trustworthiness, not to replace it!

We did not evaluate how students react to the moves described above, whether they notice them and whether they take them as signs of trustworthiness. Also, while we think that students trusting teachers is important, students of course still need to remain critical, dare to challenge their teachers, and not just blindly follow (Kelland, 2025).

We are currently conducting more focus group interviews, including with more students, as it became clear already in those first five interviews that it is not just the relationship between teachers and students that is affected, but also the relationships within each of the groups when there is the perception that someone is taking the easy way out, with or worse without admitting to it.

The sudden emergence of a technology which has the potential to undermine traditional methods of teaching and examination has led to a great deal of uncertainty for both teachers and students. We suggest using conversations about GenAI as a trust-building opportunity and provide a compilation of trust moves that teachers in our focus groups reported using.

We want to end by telling teachers: Trust yourself! You do have the competence and the compassion to engage in conversations about GenAI with students, even without being an expert on GenAI. We encourage you to build on the trust moves we report, or to come up with your own ways of approaching the topic. But do make the first move and talk with your students. It will make teaching and learning so much easier and rewarding for everybody!

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the teachers and students that opened up in the focus group interviews, and who shared personal experiences and thoughts with us and each other.

References

Bašić, Ž., Banovac, A., Kružić, I., & Jerković, I. (2023). ChatGPT-3.5 as writing assistance in students’ essays. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 750. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02269-7

Farazouli, A., Cerratto-Pargman, T., Bolander-Laksov, K., & McGrath, C. (2023). Hello GPT! Goodbye home examination? An exploratory study of AI chatbots impact on university teachers’ assessment practices. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2241676

Felten, P., Forsyth, R., & Sutherland, K. (2023). Building Trust in the Classroom: A Conceptual Model for Teachers, Scholars, and Academic Developers in Higher Education. Teaching & Learning Inquiry: The ISSOTL Journal, 11 (July).

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive success in college: JHU Press.

Glessmer, M. S., Persson, P., & Forsyth, R. (2025). Engineering students trust teachers who ask, listen, and respond. International Journal for Academic Development, 30(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2024.2438224

Kelland, L. (2025). The ambiguity of trust in Higher Education. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 13(SI2), 119–131.

Loft, V. (2025), Just Say Anything! What Students Wish Their Teachers Did About GenAI. Paper presented at the LTH Inspiration Conference 2025, Lund.

Macfarlane, B. (2022). The distrust of students as learners: Myths and realities. In Trusting in higher education: A multifaceted discussion of trust in and for higher education in Norway and the United Kingdom (pp. 89–100). Springer.

Zhai, X., Nyaaba, M., & Ma, W. (2024). Can Generative AI and ChatGPT Outperform Humans on Cognitive-Demanding Problem-Solving Tasks in Science? Science & Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-024-00496-1

Zhou, Z. (2023). Towards a New Definition of Trust for Teaching in Higher Education. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 17(2), 2

Cite as:

Forsyth, R., and Glessmer, M. S. (2025). How teachers build trust with students in the presence of GenAI. LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025

https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/C1_Forsyth_Glessmer.pdf