The Spiral of Silence, or why it is so difficult to talk about sustainability (updated)

I like using the “Spiral of Silence” when talking about why it is so difficult to talk about sustainability, so here comes an updated version!

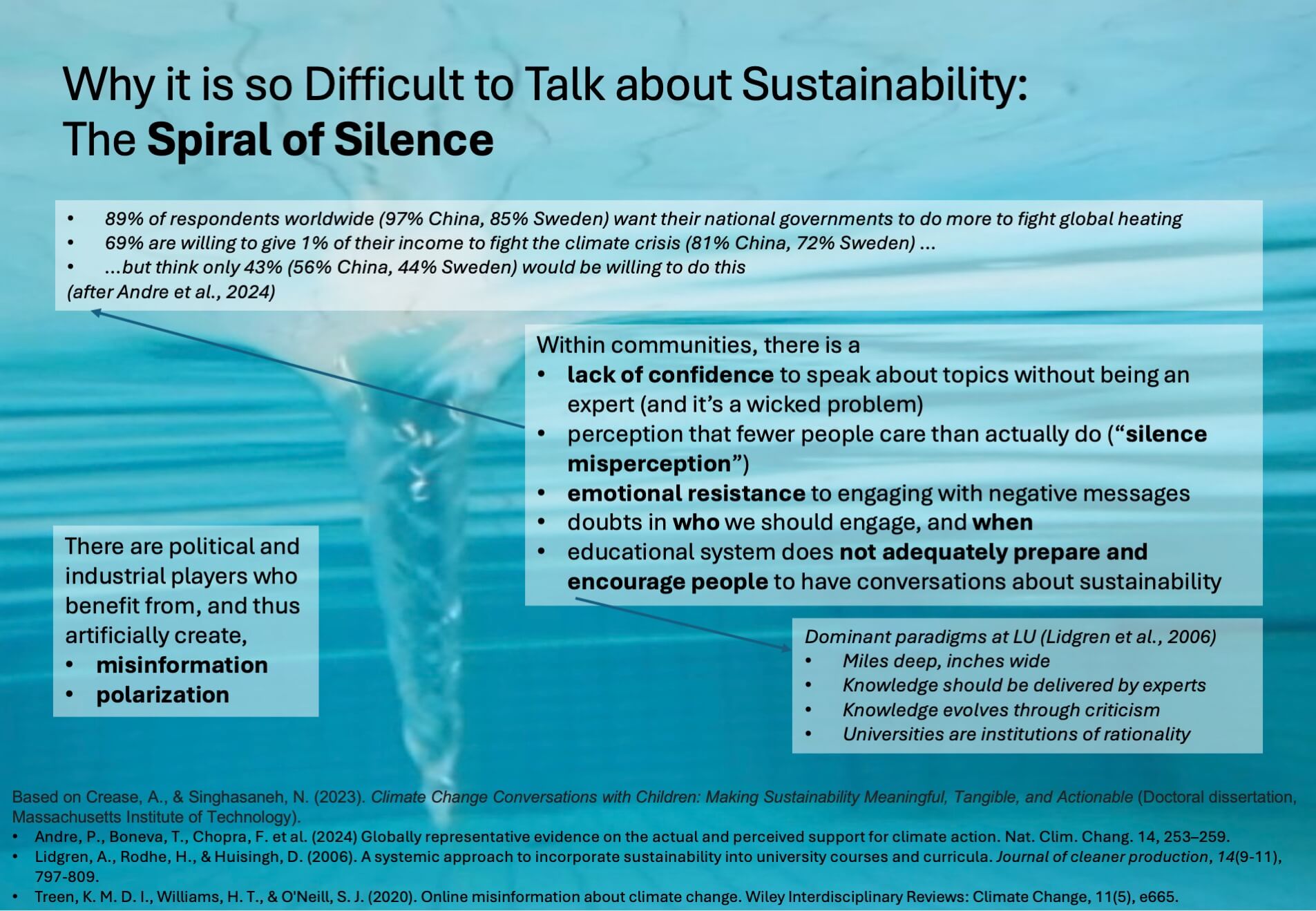

The idea for the “Spiral of Silence” is borrowed from a thesis about climate change conversations with children by Crease & Singhasaneh (2023), but I think it is a very helpful model even when thinking about talking about sustainability in higher education classrooms, or in everyday conversations, since it explains many external and internal facets that make it so difficult to have these conversations. The first one is external, but then all the rest are internal.

Artificially created misinformation and polarisation

There are political and economical reasons for many people to not want to have good conversations about sustainability, so there are powerful actors that benefit from, and thus artificially create, misinformation and polarisation.

We are seeing so many examples of this play out right now, and it has been well-documented for some time. For example Treen et al. (2020) identify four variants of climate science denial (trend denial (no significant warming is taking place), attribution denial (it is not anthropogenic), impact denial (it will not have significant negative impact on humans or the environment), and consensus denial (there is no consensus amongst climate scientists about anthropogenic climate change)) and how those are created: funded by corporate or philanthropic actors, produced by organisations, and then diffused through influencers and different echo chambers to the public, with the purpose to misinform and polarise.

But also within communities and within ourselves, there are several factors that make conversations difficult.

Lack of confidence

Many people (including many teachers) feel that they don’t know enough to have conversations about sustainability. That is very relatable, but the problem is that it is a wicked problem, meaning that there is no one right solution, so there are also no experts that have a solution. Everybody has a lack of knowledge about some aspects, and we have to get over that and still engage in conversations, but be prepared to learn from and with each other, and educate ourselves. We will make mistakes, but the process is the point.

And apparently the fear of being perceived as not competent is a big factor in not having conversations: Geiger & Swim (2016) find that “the reason that those who believe that most others doubt climate change are less willing to discuss the topic than those who accurately perceive others’ opinions is because the former expect to lose respect (appear less competent) in a discussion, and not because they expect to be disliked (perceived as less warm)“.

Silence misperception

Sustainability is everywhere as a buzzword, but there are only few good conversations happening about it. This prevailing silence makes it seem like it is not a topic that matters to people (because otherwise they would surely be talking about it?). And that is of course a vicious circle – if we don’t talk about it because so few other people are talking about it, what will encourage them to keep talking, or get more people engaged in the conversation?

There is actually a lot of research into the silence misperception. Andre et al. (2024) find that worldwide, 89% of respondents to a survey want their government to take more action, 69% would be willing to give 1% of the income to fight climate change, but only 43% believed that others would be willing to do the same. It is quite fascinating to look into their supplementary material — in China, the world’s top polluter, 97% want their government to do more, 80.9% are willing to pay 1%, and think 56% of others would be willing to do the same. Compare that to Sweden (84.6% demand more political action, 71.8% willing to contribute 1% of income, believe that 44% would be willing to do the same), Germany (85.9%; 67.9%; 39.5%), USA (74.0%;48.1%; 33.2%))… Taken together with the study mentioned above about the lack of confidence to speak up when one has the wrong idea of the proportion of the population who wants climate action, these results are really worrying and mean that we really need to speak more both about the real numbers and then the actual topic.

Emotional resistance

There is also just plain emotional resistance against engaging with negative messages, and that is a powerful obstacle to conversations or engagement. Who wants to bring down the mood, others or their own, or even provoke other strong emotions? Maybe understanding eco-anxiety and how to deal with it can help here, as well as just having the conversations despite the emotional resistance.

Doubts who to talk with and when

People have doubts about who to talk to, and when. We don’t want to take hope for a good future away from children (but then Marlis reported on a study where even 8 year old kids said that they want to be told the truth, not protected by being lied to; and also we should be careful in what kind of hope we foster; here are some helpful thoughts on constructive hope), or overburden them at a too young age. But even at university, some teachers feel that “here, they should focus on learning x, and I want them to focus on that and not get caught up in despair or discussions that are beyond the scope of my course”. Because if we open up for conversations that students feel a need for but don’t have any other opportunity for, this might take on a dynamic of its own!

But of course at some point, someone needs to start talking somewhere, and there are so many different ways to teach about, with, in, through, for sustainability!

Educational system

Lastly, the educational system does not adequately prepare or encourage people to have these conversations. But this is where we are working for change now! :)

In addition to all the reasons above (and likely many others) for why teachers feel like they can’t (and maybe even shouldn’t) talk about sustainability, there are some rooted in institutional culture. In their study of Lund University, Lidgren et al. (2006) found several dominant paradigms that all do not really help with including sustainability as a new focus in our teaching:

- “Miles deep, inches wide“: We value extremely deep knowledge of a very narrow area, and that is how research and teaching are generally organised. But that means that an interdisciplinary topic like sustainability often feels like it should be someone else’s topic, not our own.

- “Knowledge should be delivered by experts“: I see this so much that teachers say that they are not experts on sustainability, so they cannot mention it, but instead either say that students should take specialised courses on sustainability, or that they want to invite experts into their courses to speak about sustainability.

- “Knowledge evolves through criticism“: Criticism is generally not threatening, since teachers are also “miles deep, inches wide” experts in their topics, but expecting criticism on our teaching in a subject that we also feel we are not experts in, while we believe that knowledge should be delivered by experts, is of course off-putting. However, based on believing in this paradigm, if we constructively criticised current teaching, teachers might start to change their teaching (which is also what we see).

- “A university is an institution of rationality“: This is an image that seems very important for universities, also in a context not mentioned here, and that is that an approach to talking about “the end of the world as we know it” or any other language that takes the current polycrisis as serious at it is, is often easily dismissed as “too emotional” and therefore not rational. But the problem with this paradigm is that if we assume that universities to be rational, it is easy to assume that if sustainability or climate change were really such big deals, there would be some rule in place that every teacher or program had to do something about it. But since there isn’t, it’s easy to think “how bad can it be? When it becomes really urgent, someone will tell me to do something about it”.

So these paradigms are really playing against any attempt to start talking about new topics and including them in teaching, and whenever I talk about them with teachers, people recognise them and how they influence thinking and practice.

I find this Spiral of Silence so helpful because it shows how complex the problem is. It is not just that there are players who don’t want us to talk about sustainability, even within ourselves there are so many obstacles to overcome! But becoming aware of those is a good first step, and then reflecting on which of those (and possibly other) obstacles are relevant in our individual case, and how we can overcome them.

Andre, P., Boneva, T., Chopra, F. et al. Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 253–259 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01925-3

Crease, A., & Singhasaneh, N. (2023). Climate Change Conversations with Children: Making Sustainability Meaningful, Tangible, and Actionable (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

Geiger, N., & Swim, J. K. (2016). Climate of silence: Pluralistic ignorance as a barrier to climate change discussion. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 47, 79-90.

Lidgren, A., Rodhe, H., & Huisingh, D. (2006). A systemic approach to incorporate sustainability into university courses and curricula. Journal of cleaner production, 14(9-11), 797-809. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652606000187

Treen, K. M. D. I., Williams, H. T., & O’Neill, S. J. (2020). Online misinformation about climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 11(5), e665.

Summary of Marlis Wullenkord’s presentation on eco-emotions – Teaching for Sustainability says:

[…] roles and representation, and “more vulnerable to social construction to silence” — see also my interpretation of the Spiral of Silence, I believe that is a very real problem!), and women are more likely to be anxious. But […]