Published! Dunnett & Glessmer (2025) “Positionality statements in engineering education: A European perspective”

Sharing is not always caring! And especially expecting others to share things about themselves that they might not be ready to share. The editorial “Positionality statements in engineering education: A European perspective” by Kirsty and myself that is now published (contact me for a pdf if you don’t have access!) has been in the works for quite some time. It started out with us mapping our our positionality in different ways (mine here, Kirsty’s here), then we discussed and read a lot. We really liked the discussion in Secules et al. (2021) until we came to their closing sentence, “If understanding our research requires understanding one another, we must become a community that continually and bravely tells one another who we are“. Do we, though? Can we demand bravery, when we know that for some people telling others who they are will make their life a lot more difficult? Should that type of bravery be a requirement for publishing research, as it is when journals require positionality statements and editors enforce this? When the alternative to potentially opening oneself up to harrasment or worse is to lie about who one is?

What we agree on is that we do not want to ask anyone to share things about themselves that they might not want to share (and that, in some contexts, might actually be dangerous to share!), and that, at the same time, it is very important that everybody thinks about their own identity and how that influences their research and teaching, and to disclose the implications of their identity on their work.

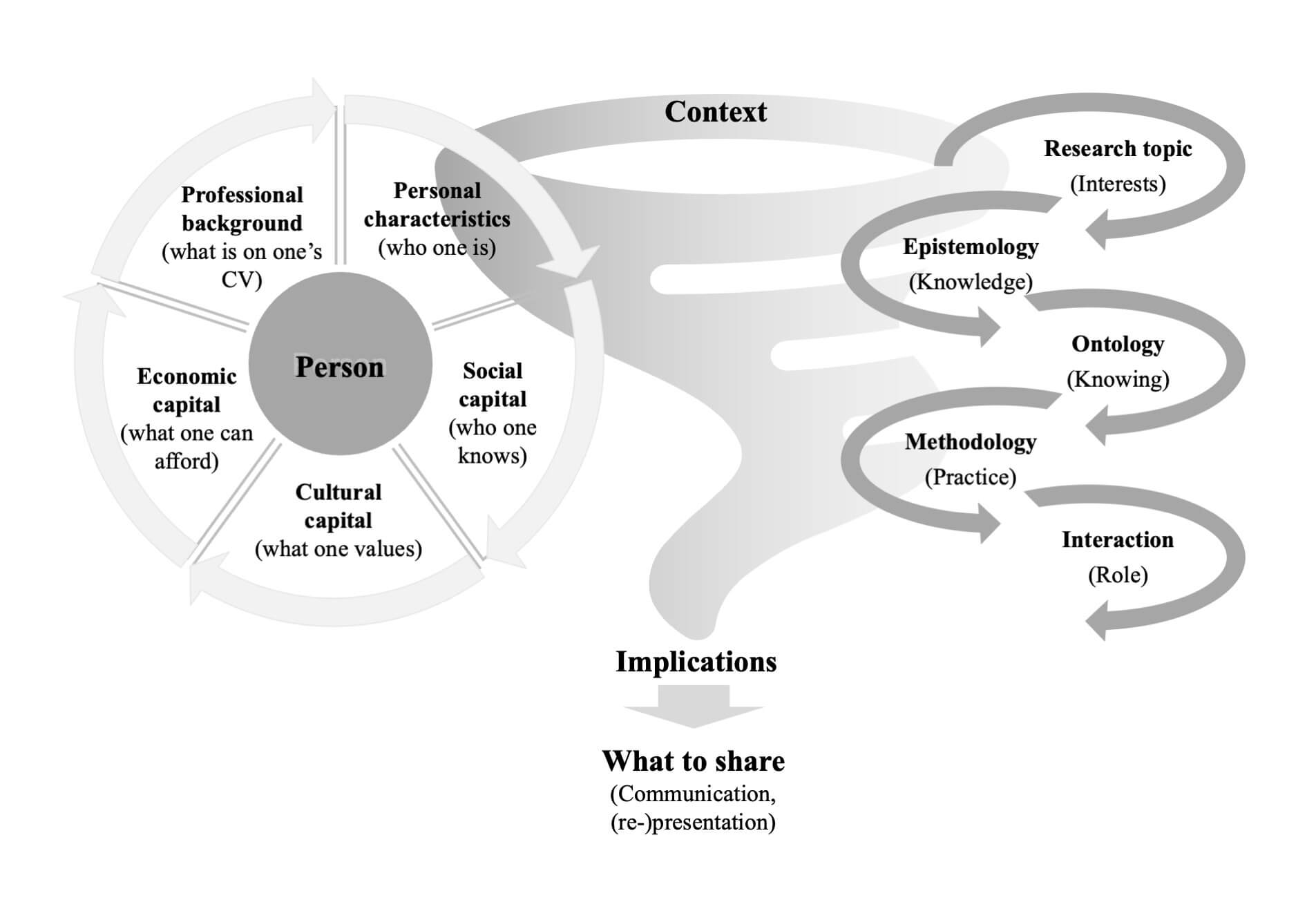

After considering different ways to prompt reflection and discussions about identity facets, like the positionality map that we both use above, we settled on defining five broad categories of identity facets (which might, in some cases, even overlap a bit) that are similar in the type of information and how easy they should be to disclose (also considering that in Europe, personal information is protected by the GDPR — hence the reference to Europe in the title of our editorial):

- Personal characteristics: personal identity facets (e.g., gender identity [including pronouns], sexual orientation, health, age, race) —> very limited disclosure, mostly afforded special protection in GDPR;

- Cultural capital: world view and understanding (e.g., religion, politics, trade unions, general knowledge, hobbies): this includes some facets often implied by the social side of “socioeconomic” —> some disclosure possible, some have special protection under GDPR, others are closely related;

- Social capital: networks and group memberships (e.g., access to influence, guidance, etc.): this includes other facets often implied by the social side of “socioeconomic” —> some disclosure possible in broad terms; details may have special protection under GDPR;

- Economic capital: financial situation; this includes the economic side of “socioeconomic”, also employment status (precariousness) —> as social capital;

- Professional background: education, affiliations, awards, employment status (role title) —> disclosure likely to be possible and often relevant.

As you see in the graphic on top of this post, we think about those five categories not as fixed or independent of each other, but some of these are likely fluid, and also which one of these are important at any given time probably depends a lot on the context.

These five categories then interact with the six aspects (of research in the original case) that Secules et al. (2021) identify:

- Research topic; i.e. why am I interested in a topic, getting acces to it, have emotions about it?

- Epistemology; i.e. how do I know what I know, what lens (critical vs objective) am I using?

- Ontology; i.e. what do I (not) observe as an insider/outsider, expecting dual consciousness or single reality?

- Methodology; i.e. what traditions do I come from, which methods do I choose?

- Relation to participants / researcher-as-instrument; i.e. how do I relate to participants through power and privilege, or access to communities?

- Communication; i.e. how do I represent myself, with my name, disclosures of identity facets, language choices?

And from the turbulent (see the tornado in the image? So proud of that one) interaction of who someone is, with the context they are in, and their interests, knowledge, way of knowing, practice, and role, everybody individually has to figure out what the relevant implications in any given context are, and then decide what to share and with whom.

We are (and didn’t have the space to write about this in the editorial, so read about here for the first time ;-)) especially interested what this means for teachers — both as participants in academic development courses, and in the classroom. In a recent Introduction to Teaching and Learning course, I first showed the “person” side of the image above and asked participants to individually reflect on three questions:

- How has your professional development so far been influenced by who you are, who you know, what you value, what you can afford, what’s on your CV?

- Which aspects do you NOT want to discuss? Why? (You will NOT have to share that with anyone!)

- Any aspects that you would like to discuss? (Can be done without mentioning personal experience!)

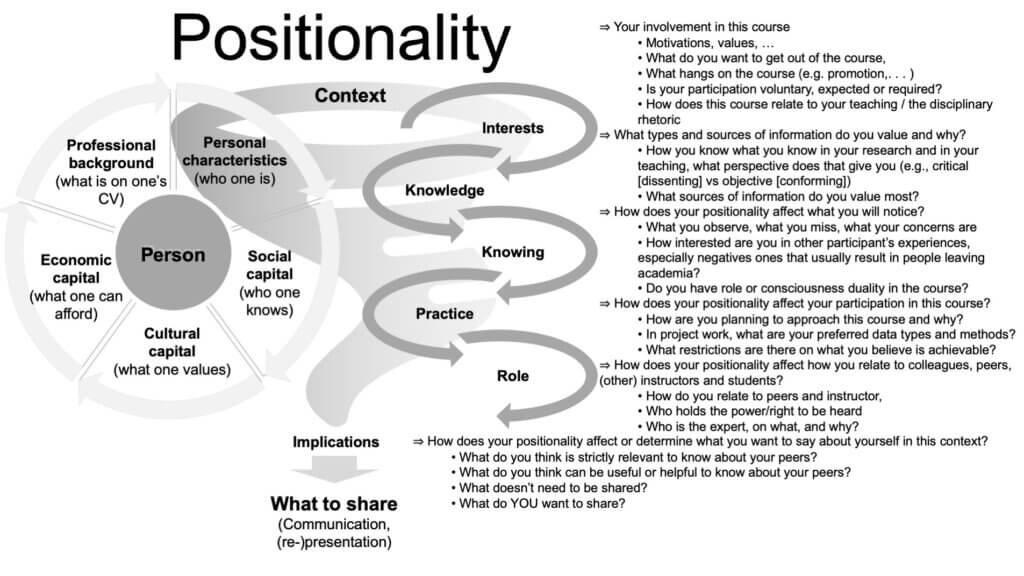

Then later, I used the image below to connect participants’ identities with what might be relevant to share in the context of the course (here we adapted the Secules et al. (2021) categories to fit to our context):

Reading through those prompts now they might need a little tweaking before I use them next time, but anyway, this led to really interesting conversations about, for example, the types and sources of information participants value, and why — in this course, we typically have 3 or so participants (out of 25) that have some experience with qualitative methods, whereas everybody else is firmly anchored in quantitative methods. Having participants connect their preferences to their educational biographies, and realising that the “preferences” might be more about never having been exposed to other methods before than based on any kind of argument, is really valuable. And the same for all the other categories.

Since this was the first test run I did with this model in my teaching, I did not go the next step yet — using similar prompts to facilitate discussion around what a teacher in a classroom might want to share about themselves. Similarly to as an author or course participant, we argue that nobody should be asked to share a bunch of labels that — ultimately — are meaningless when the interpretation of their impact is left to the prejudices of the audience. At the same time, I believe that showing up authentically as a human is crucial, and to me that means sharing the implications of who you are, who you know, what you value, what you can afford, and what’s on your CV influence for what you do with your work and life. And hopefully this tool can help people figure out what that might mean depending on context, and what they want to share.

Any questions or comments? Always happy to discuss!

Dunnett, K. and Glessmer, M. S. (2025), Positionality statements in engineering education: A European perspective. J Eng Educ, 114: e70014. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.70014

About our process… Hard to believe, but the image below shows the state of a 47 page draft after a coaching session with Klara over lunch (thank you!!), and at the end of the day we were almost down to the 1500 words we were allowed to write for the editorial! Sometimes physically bringing scissors into the writing process really is the best way to deal with a lot of words…

Roxå et al. (2025): "Entangled in context: addressing academic development and choice architecture" - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] and relating to the discussion around positionality statements I wrote about yesterday, reporting on the context of any kind of academic […]