Currently reading about SDGs, education for wonder, and academic activism

As many other places in the world, my university works with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a framework, and for many researchers and teachers pointing to one or two of the goals is a common justification of why their research is relevant and important. But in many cases, the SDGs are not used in more depth than as catch phrases. Seeing that we are almost in 2030 and not a lot of progress has been made on the goals, it’s probably timely to think about what comes next (and that’s where I go into a bit of a rabbit hole of reading).

Already in 2020, Kopnina wrote the article “Education for the future? Critical evaluation of education for sustainable development goals”. So what are the problems?

Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG) is about educating students to take action for sustainable development as described in the SDGs. The SDGs bring together social, economic and environmental goals (or triple p: people, profit, planet). However, the assumption that the three can be achieved together is — an assumption, and one without a strong foundation in anything. Since the three p’s are in conflict with each other, what happens in practice is a focus on the economy over people, and on both over the environment.

One problem are the condescending assumptions summarised under the term “cognitive imperialism”: That the superior schooling of the developed western world should be spread throughout the underdeveloped world, and that in doing so, nothing worth keeping will be lost.

Another problem is the SDG’s focus on people and neglect of all the other, non-human life on Earth, which is intrinsically valuable and worthy of protection and care, not just when it suits economic goals. But when focussing on SGDs 1 and 2 — no poverty and no hunger — there are no suggestions for how this should be achievable without exploiting more of the planet’s resources, converting more areas into farmland, etc..

In contrast to ESDG, Kopnina (2020) calls for sustainability education which “aims to foster learners to be creative and responsible global citizens who critically reflect on the ideas of sustainable development and the values that underlie them“. Ecocentric, critical pedagogies are about emancipatory learning, and there are many different flavours to choose from. Ecopedagogy, for example, “focuses on sustaining all life, based on learners’ understanding of interconnectedness between every element of living and non-living things“; empowerment education emphasises the “need to address the interaction of the human population, food production, and biodiversity protection through concepts of human rights, women’s rights, and foremost education“, with a focus for example on preventing unwanted pregnancies.

All these critical approaches are not necessarily in contrast with ESDG though. The author stresses that there are likely no sinister motives behind the seemingly universal acceptance of the SDGs and the resulting ESDG: “The rapid spread of the SDG-supporting institutions, including the author’s own university, is probably due to nothing more sinister than indifferent management, and a dull-minded rehearsal of received “truths” (e.g., the triple bottom line), rather than a serious effort to rein in alternative visions. Embrace of ESDG is likely just a self-limiting response to the imperative to be pragmatic or inclusive of all issues that society considers important, logical outcome of pluralism and democracy“. So then let’s stop self-limiting? One of the footnotes in Kopnina (2020) brings up a really interesting point: Education for anything might be seen as, or in fact be, indoctrination, rather than education that also works for subjectification. They make the point that “this critique seems to under-estimate the power of the dominant education, which is currently dictating the economic vision of what human progress is, top-down, for the entire world“. And if education for sustainability is approached as a critical pedagogy, that carries with it a critical approach also towards itself.

In one of the last sentences of Kopnina (2020), there is a mention of “education for wonder”, which I then absolutely had to look up, because it sounds like what I have always tried to do; with #KitchenOceanography, with #WaveWatching, with my active lunch breaks, even in the “seeing the world with new eyes”-motto when I was working in science communication for GEO.

So what is “education for wonder” about? In the referenced article, Washington (2018) describes “education for wonder” as an ecocentric education, “rejuvenating a sense of wonder towards nature is essential to ecocentric education and to finding a sustainable future“. We need to “help humanity feel that nature has intrinsic value that should be morally considered“, and for that, we “need the opportunity to form a personal connection to the nonhuman“. Deep wonder is part of all religions and philosophies, so it can, and probably should, play a central part in all educations.

So why isn’t it? One part of that is that most people live in cities these days and just do not have regular extended experiences with nature any more, and therefore do not feel a deep connection. With an anthropocentric worldview, rather than feeling one with nature, we position ourselves as disconnected from it, and as more important; and nature as something we should, and can, dominate. By also separating our feelings from our intellect and prioritising the latter, we further distance ourselves from nature.

Washington (2018) postulates that education for wonder should start with kids, already at home and in schools, and then continue on through university and into communities. Suggestions here resonate with other sources I have recently been reading and enjoying: for example Venet’s (2024) “sit spot”, or Holmqvist & Millenberg (2024)’s “wandering in a place rather than through it”. Washington (2018) recommends a great resource: the “exploring a sense of place” guidebook which is a super practical guide for exploring a place and creating programs for the community (including checklists! I love checklists!) based on the premise that “every place has its story”. There are so many stories to discover in every place, at least the ones elaborated on in the guide: a deep-time geologic story, a weather and climate story, a seasons story, a story of indigenous people, a watershed story, and a wildlife story. I definitely want to play with this some more!

When I recently used my active lunch break in a course with university teachers, many of the examples of what they saw and related back to their discipline were examples filled with wonder. There were a lot of pictures of the very first spring flowers of the year related to how they draw nutriens from water and air and use them to grow, there was a picture of a tree and a reflection on the processes that bring water to the highest ends of the thinnest twigs. Wonder is everywhere if we take the time to look for it!

One surprising recommendation in Washington (2018) that I did not see coming is that all universities should become wonder hubs by “teaching how to solve problems through activism“.

So then, activism. As luck would have it, I have something on my to-read pile there, too: Thomas-Walters et al. (2025) on “The impacts of climate activism”. In a review of 50 studies, mostly from the US and Western Europe, they find that climate activism can lead to a lot of public and media attention to organisations conducting the protests, increase in online searches for that organisation or protest, and generally lead to increased public support of the cause IF the protest is peaceful, even if it was disruptive. The “radical flank effect” can happen, where the actions of an extreme group increase support for more moderate groups working for the same cause. The radical flank effect can also help move the “Overton Window” of what is accepted in society. Climate activism can also influence voting behaviour and gain policymaker attention. For Germany, Thomas-Walters et al. (2025) cite studies that showed that exposure (and especially repeat exposure) to Fridays for Future protests shifted voting behaviour towards the Green party, or at least from AFD to CDU. But Fridays for Future are primarily young people, what is the effect of academics participating in climate activism?

This is investigated by Fossen (2025) in “Academic Activism and the Climate Crisis: Should Scholars Protest?”. Apparently, a common call (which I hadn’t heard before, but I like a good pun!) is for scholars to shift “from publications to public actions“. Scholars are doing that for example by engaging in academic climate activism in Scientist Rebellion, where civil disobedience actions are expressions of their roles as academics. That people are protesting in this role, in contrast to their role as citizens, is marked by wearing lab coats. This can be perceived as conflicting both with their role as academic AND as citizen, because of the idea that academics should stick to facts, not interpret them into policy; and because stressing the role as academics in order to make the protest more impactful seems to devalue voices of other citizens who aren’t academics. And I have been struggling with that quite a bit. While I am part of some amazing academic activism groups, I have also met quite some “but I have a PhD on some unrelated topic, so I know better than anyone else and everybody should listen to me!” people, and that is an attitude that I really do not want to be associated with and that is also really unhelpful if you want to engage in dialogue. But now this article provides a really helpful way to think about academic activism!

Science can happen anywhere on the spectrum between the “ivory tower” type research where people argue that they are just looking for “the truth”, and critical approaches to science. Fossen (2025) states that “a neutral position is not available to begin with, since uncritical scholarship contributes to maintaining the status quo“. But still somewhere in the middle of the spectrum, there is an approach that is based on two assumptions: 1. science is socially embedded (i.e. science is shaped by power and money, and science has to play a role in the world); and 2. there is a tension between the role as scientist and that of activist or policymaker. Within this approach, scientists have to make sure the world knows about their results (or, as we quoted Sir Mark Walport earlier, “science isn’t finished until it’s communicated”). Fossen (2025) gives an example for the social responsibility to communicate research findings: the ozone hole. If scientists hadn’t warned about it, despite some push-back from within the scientific community that that wasn’t their role, nothing could have been done about it, and it would now be dangerous to go outside.

But “who is supposed to warn whom of what, why, and how?”

Fossen (2025) suggests that not just academics working on climate questions, but all academics “have a professional responsibility to let the warnings of their colleagues sink in and move them to action“. And that responsibility is not just about making sure that warnings about climate change, specifically, are taken seriously, but about making sure that scientific results in general are heard, especially when there are actors putting a lot of money and effort into suppressing scientific results in the public debate. “When the conditions for scientists’ warnings to sink in are undermined, and part of science’s public function is thwarted, this provides a basis for defending the involvement of the academic community as a whole, not just scholars working on climate change“. Fossen (2025) stresses that “the need to publicly take a stand as a community is reinforced by the fact that diffusion of scientific understanding and responsiveness to it has been actively undermined through lobbying and disinformation. The efforts by the fossil fuel industry and their allies to discredit climate science and thwart its potential contribution to policy formation undermine science as an institution, contravene its basic aim of fostering understanding, and inhibit its social function. This, too, concerns the academic community as a whole“. So what scientists, not just climate scientists but scientists in general, should be working towards is that research findings are heard, taken seriously and acted upon. What exactly that action should look like then maybe needs to be determined in discussion with experts of all relevant fields, but making sure that research results are on the table and carry weight is something that we all need to help ensure.

Fossen (2025) writes, my emphasis: “To sum up: the activist role for the academic community in the climate crisis lies in enabling experts on climate change to fulfill their duty to warn by countering attempts to frustrate their sentinel role and helping to let their warnings sink in. What sets apart academics from other fellow citizens is not that, because we are academics, we know what needs to be done about climate change. It is rather that we have a special tie to this institution—the academic community—which has a twofold special role in the climate crisis: as both revealing the problem, and being thwarted in successfully playing its social role by actors who perceive its findings as a threat to their interests“. So it is not about scientists being smarter than everybody else, but about them being part of a community who is being undermined as a whole if climate sciences aren’t listened to: “Instead of elevating one’s own judgment above that of fellow citizens, one defers to the deliverances of a communal enterprise with which one is associated, and draws attention to the political system’s lack of responsiveness to those deliverances“. And, similarly to how witnesses of microaggressions need to consider the effect of observing but not intervening, “It is crucial, furthermore, that we also consider the credibility effects of failing to stand up as a community, in the face of the heightening global emergency and the persistent political failure to effectively address it“.

But then how to protest? Why the lab coats? Again with my emphasis: “academics protesting in lab coats defy expectations and interrupt the normal course of things, precisely because this is not normally part of their role. They signal, by showing rather than just telling, that there is a breakdown of responsiveness to the deliverances of scientific inquiry. Being seen to participate sends a much stronger message than just verbally endorsing protests: it shows that you really believe what you are saying. In this respect, activism may well enhance credibility, by resolving the performative contradiction of proceeding with business as usual in the face of emergency. It also enables others to see the problem as calling for action by overcoming paralysis and exemplifying a concrete way of taking action”

That was really helpful to read!

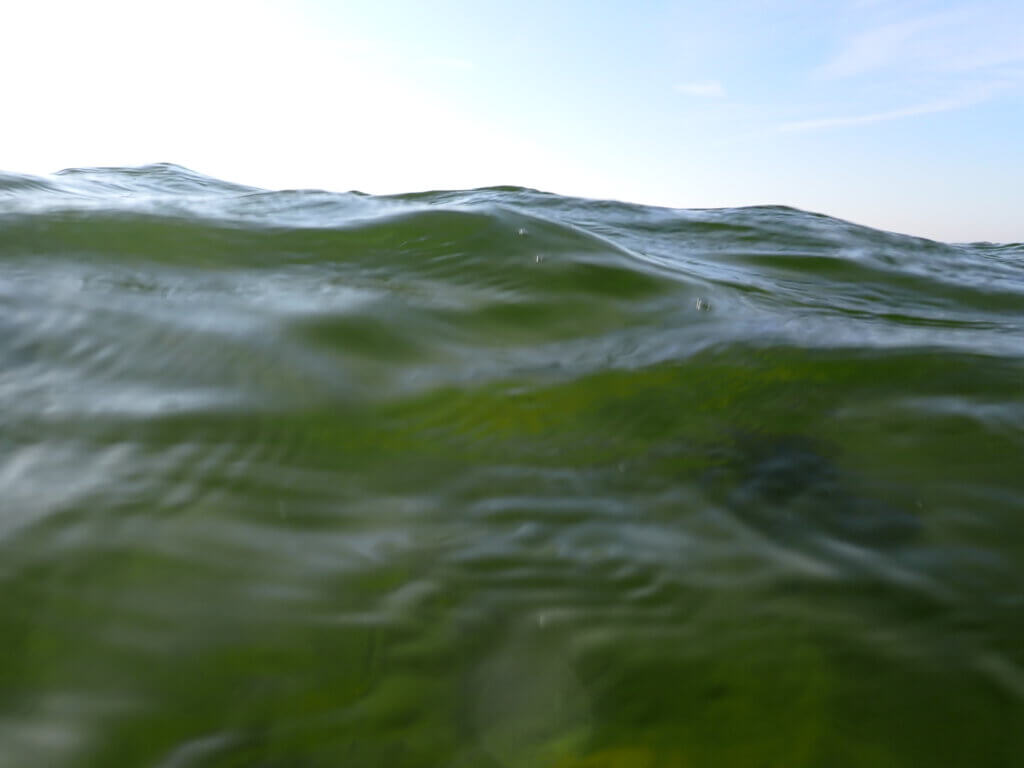

Pictures from an Easter week walk and dip.

Look at the beautiful water! Always so fascinating how different the colors are depending on which direction you look at! So blue towards the sun…

And a lot greener at a 90 degree angle, plus here we can actually look into the water at steeper angles.

Love the chequerboard interference pattern of those groups of capillary waves!

More waves, more interference! Why is it now so much greener when it was so blue before? Who knows…

Did I mention I love how all these different wavelengths exist at the same time?

Fossen, T. (2025). Academic Activism and the Climate Crisis: Should Scholars Protest?. Perspectives on Politics, 1-16. doi:10.1017/S1537592725000350

Kopnina, H. (2020) Education for the future? Critical evaluation of education for sustainable development goals, The Journal of Environmental Education, 51:4, 280-291, doi:10.1080/00958964.2019.1710444

Thomas-Walters, L., Scheuch, E. G., Ong, A., & Goldberg, M. H. (2025). The impacts of climate activism. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 63, 101498. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2025.101498

Washington, H. (2018). Education for wonder. Education Sciences, 8(3), 125–139. doi:10.3390/educsci8030125