Using rubrics

I’ve been a fan of working with rubrics for a long time, but somehow I don’t seem to have blogged about it. So here we go!

Rubrics are basically tables of learning outcomes. The rows give different criteria that are to be assessed, and then performance at (typically three) different levels is described. Below, I’ll talk about the benefits that working with rubrics have for both teachers and students, and give two concrete examples of how we used them and why that was helpful.

Rubrics are a great tool for teachers

- Designing a rubric makes you really think long and hard about what it is that you want students to be able to demonstrate for the different criteria, and how you would distinguish an ok performance from a good performance for each criterion.

- Once the rubric is set up, grading becomes a lot easier. Instead of having to think about how well any given response answers your question, now it’s basically about putting crosses in the relevant cells matching the performance you see in front of you.

- This makes it a lot easier when there are many people involved in grading — the dreaded “but x got a point for y and I didn’t!”-discussions become a lot fewer because now grading is a lot more objective

- Giving feedback also becomes a lot easier, since all the performance descriptions are already there and it’s now basically about copy&paste (or even sharing the crossed-through rubric) to show “this is where you are at” and “this is what I was expecting”.

- It also helps in course planning…

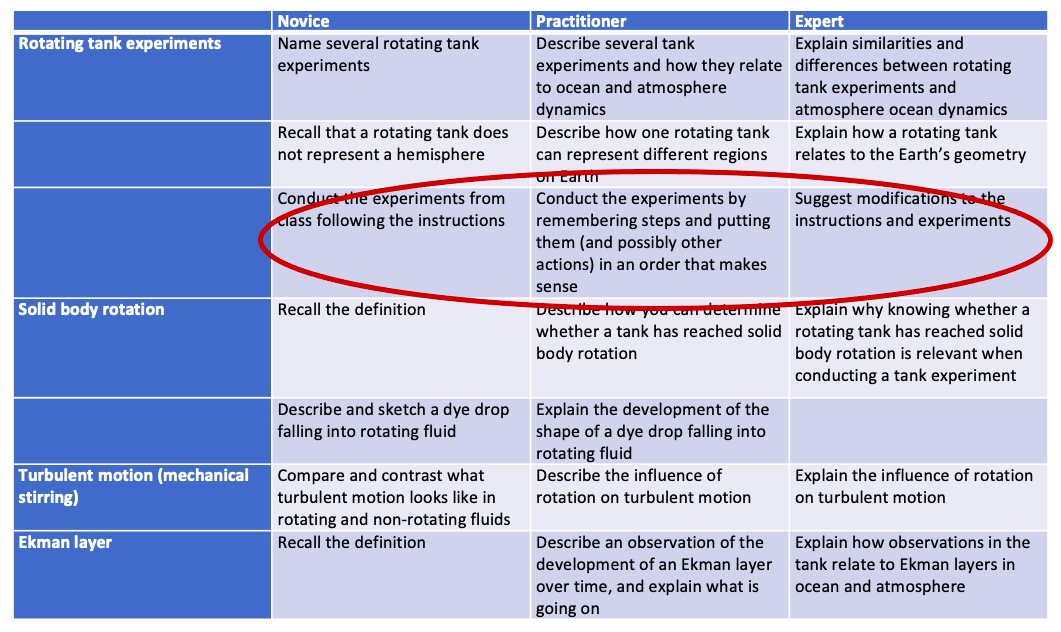

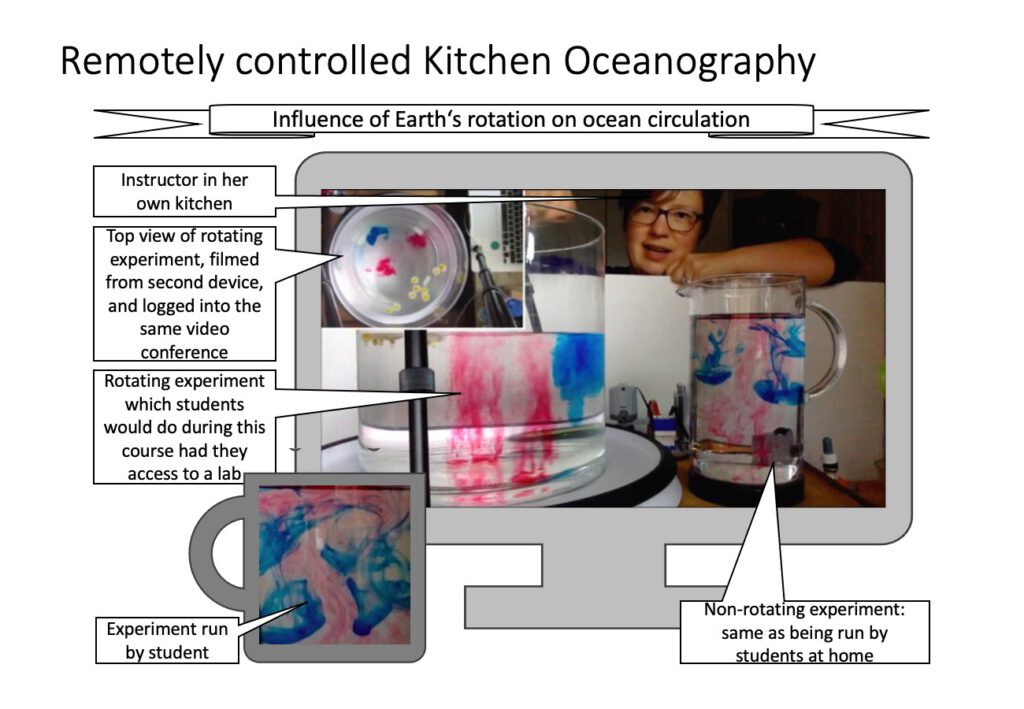

One example of where I was really glad we did have a rubric is the project that Torge and I collaborated on: We bought four cheap setups for rotating tank experiments and designed a course around making otherwise really unintuitive and difficult to observe concepts not only visible, but manipulating them in order to gain a deeper understanding. We had written down a rubric pre-corona, but when we went into lockdown in March 2020, having the rubric helped us a lot in quickly figuring out how to transfer a very much hands-on course online. Since we had clearly identified the learning outcomes, it became very easy to think of alternative ways to teach them virtually. The figure above shows part of the rubric, and circled in red is the only learning outcome in that selection (of a lesson that we thought was all about the hands-on experience!) that wasn’t just as well taught virtually. But looking closely at the rubric, we realised that the students did not actually need to necessarily do the rotating experiments themselves, as long as they were doing some kind of experiment themselves to practice conducting experiments following lab instructions. With the rubric, we had a checklist of “this is what they need to be able to do at the end of class” to directly convert into activities. We ended up with me showing the rotating experiments from my kitchen, while the students were doing non-rotating experiments, using only readily available household items, from their homes. Without the very explicit learning outcomes in our rubric, converting the course would probably been a lot more difficult.

Rubrics are also great for students

- They get a comprehensive overview over what the instructor actually expects from them

- They can use the rubric to make sure they “tick all the boxes”, or strategically decide where to put their time and effort

- Instructor feedback is now a lot more helpful than “2 out of 5 points”.

Kjersti shares an example of how she “negotiated” rubrics in her GEOF105 class to co-create it with her students:

The goal is to invite students to negotiate an assessment rubric for written assignments. We have tested this out in the following way:

- The teacher drafted a rubric and assigned an equal weighting of 5 points to each assessment criteria (15 criteria gave a total score of 75 points).

- The students voted anonymously for which criteria they wanted to assign a stronger weighting. We made no limits in how many criteria each student could vote for.

- The votes were counted up, and the remaining 25 points in the assessment were distributed based on the number of votes for each criterion.

The two criteria most students voted to weight stronger, were the structure of the lab report and the reflection part. I suspect they wanted more points for the structure partly because it is not too difficult, but also because they spend much time figuring out how a lab report should look. I also found it interesting that they wanted more points for reflection. Last year we asked the students to write a reflection paragraph that would not be assessed. We thought it would be stressful for the students to write the reflection knowing it would be evaluated. But, I guess we were wrong!

They also wanted more point for making/discussing hypothesis, using good illustrations and relating the experiment tank to the Earths geometry — all of which are objectively difficult parts of the lab report.

We found two main results after using the negotiated rubric:

- The students (on average) achieved higher scores than the previous year (were the rubric was fixed)

- The students made fewer complaints to the assignment score

We think the students achieved higher scores because they spent more time getting acquainted with the rubric before writing their assignments and could use it more constructively as a checklist.

So those are our experiences with using rubrics. How about you? We’d love to hear from you!

Co-creating rubrics? Currently reading Fraile et al. (2017) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] reached them. Kjersti has even negotiated rubrics with her class, which she describes and discusses here. And now I read an article on “Co-creating rubrics: The effects on self-regulated learning, […]

Letting students choose the format of their assessment - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] have the same level of “difficulty”, that it’s a fair assignment? This is where rubrics come in. Your rubric might assess several categories: First and foremost, the one directly related […]