Tag: #sciart

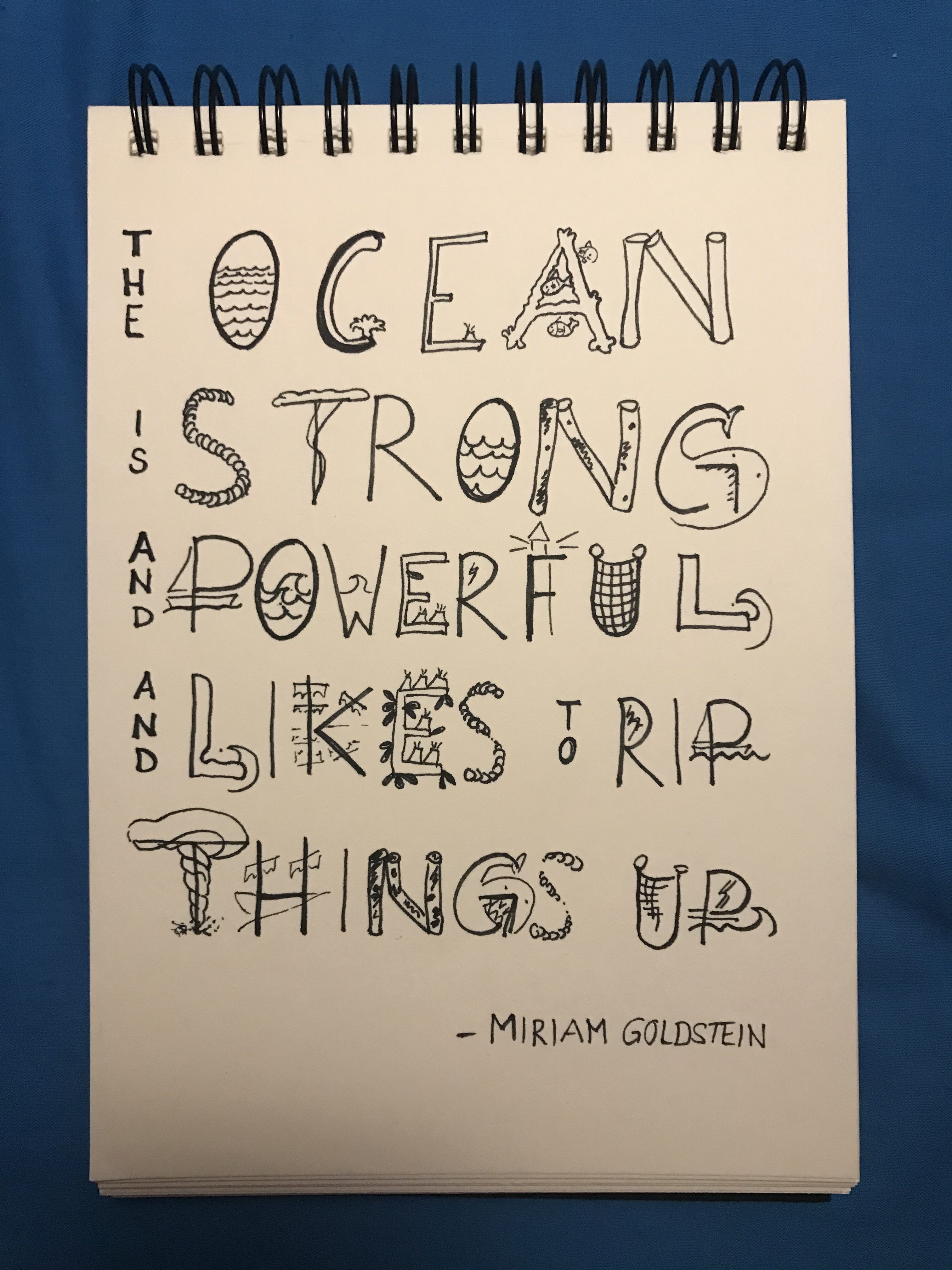

Favourite quote by Miriam Goldstein: “The ocean is strong and powerful and it likes to rip things up”

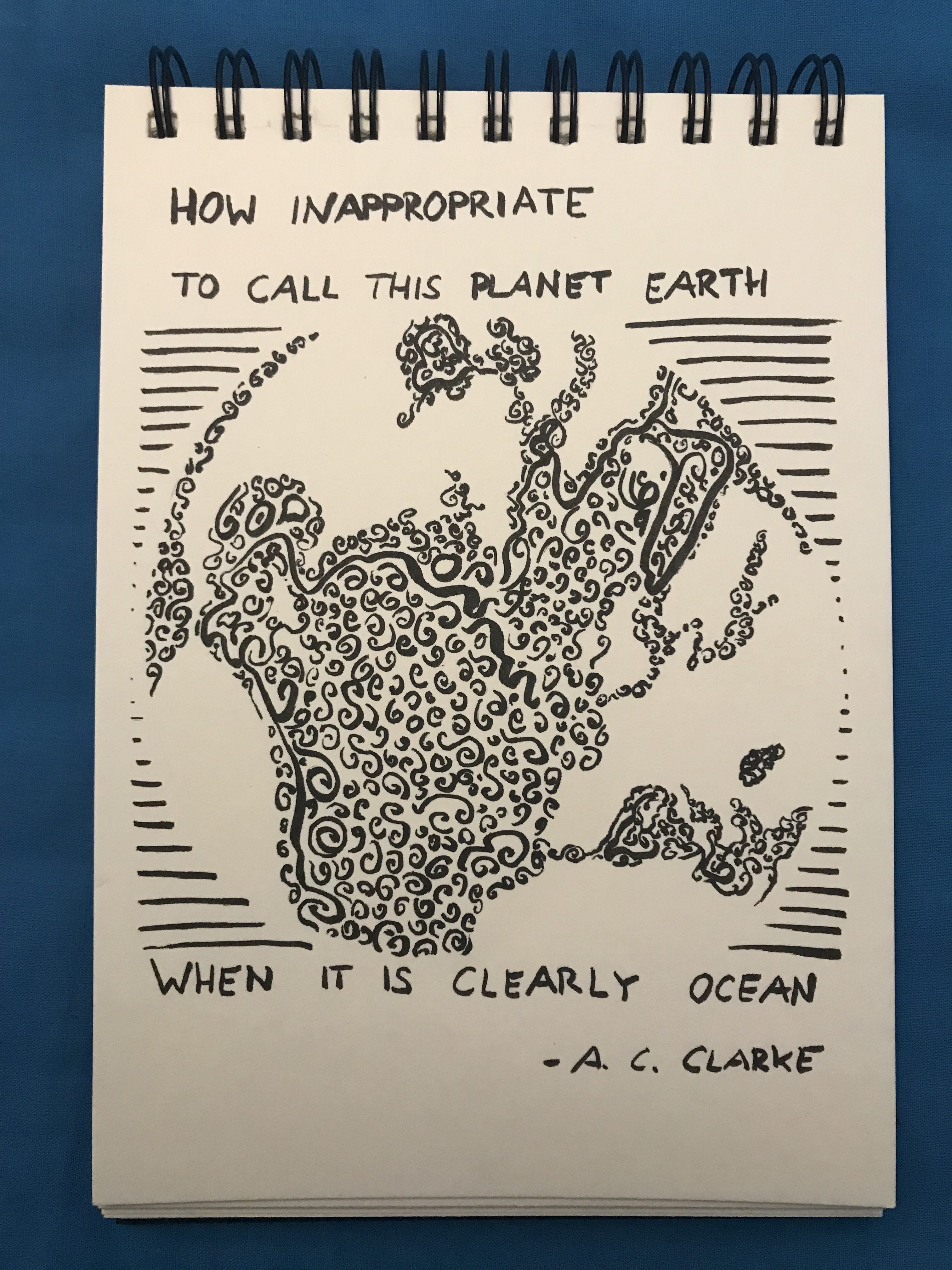

I am so lazy (or so efficient?) that even my doodles are multi purpose. Like this one, which is one of my three favourite ocean-related quotes I promised to illustrate to celebrate my blog’s 6th Birthday, and it’s also my submission to September’s #scicommchall on drawing the inspiration to your work. Kim suggested I should draw […]

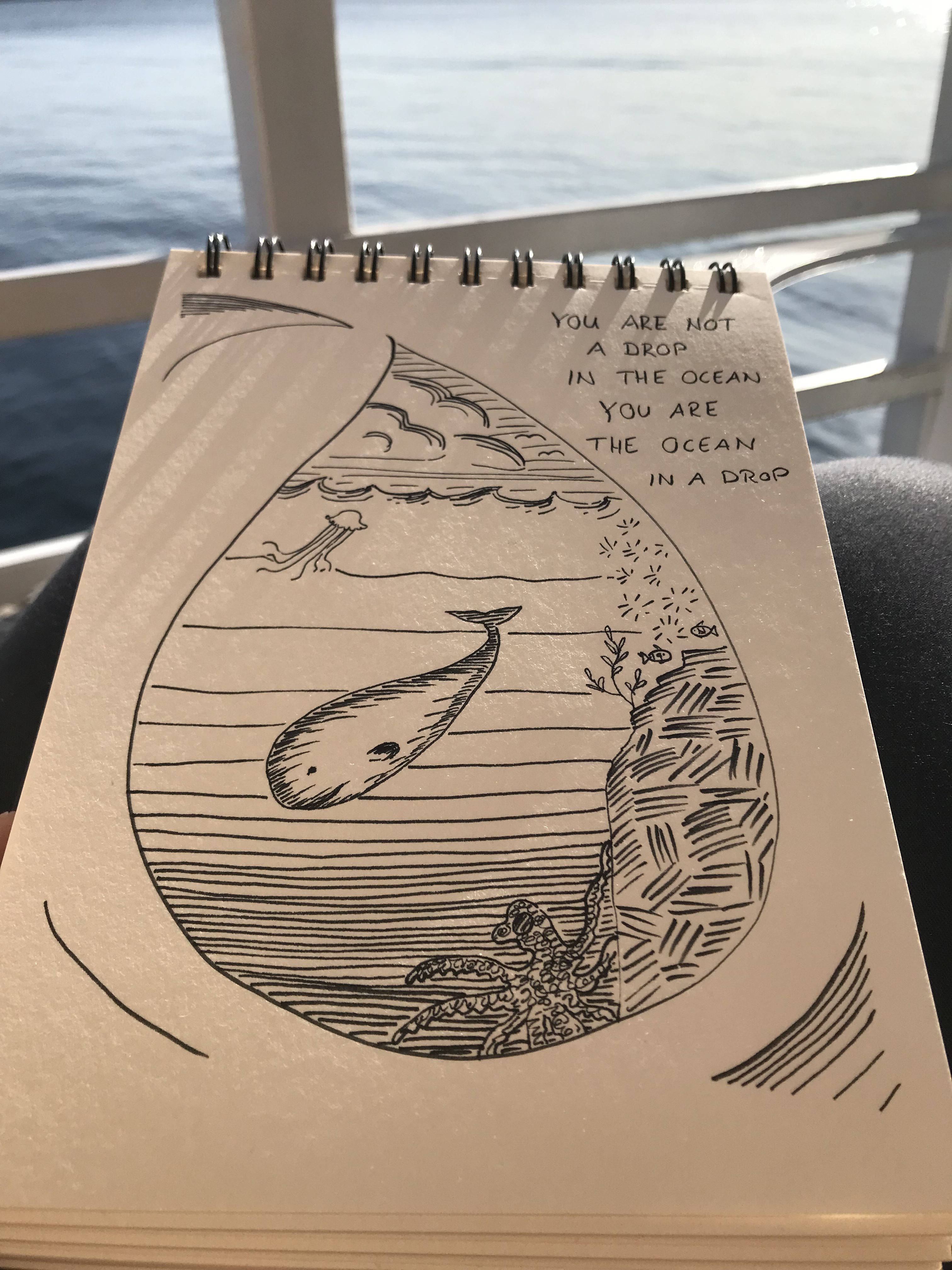

New favourite ocean quote: You are not a drop in the ocean, you are the ocean in a drop

As part of my blog’s 6th Birthday celebration, I asked you to submit your favourite ocean quotes so I could illustrate them for you. This is what Benjamin suggested (and I love it!). P.S.: The quote might be by Rumi, but in total, my internet research was inconclusive as to the original source. Since I […]

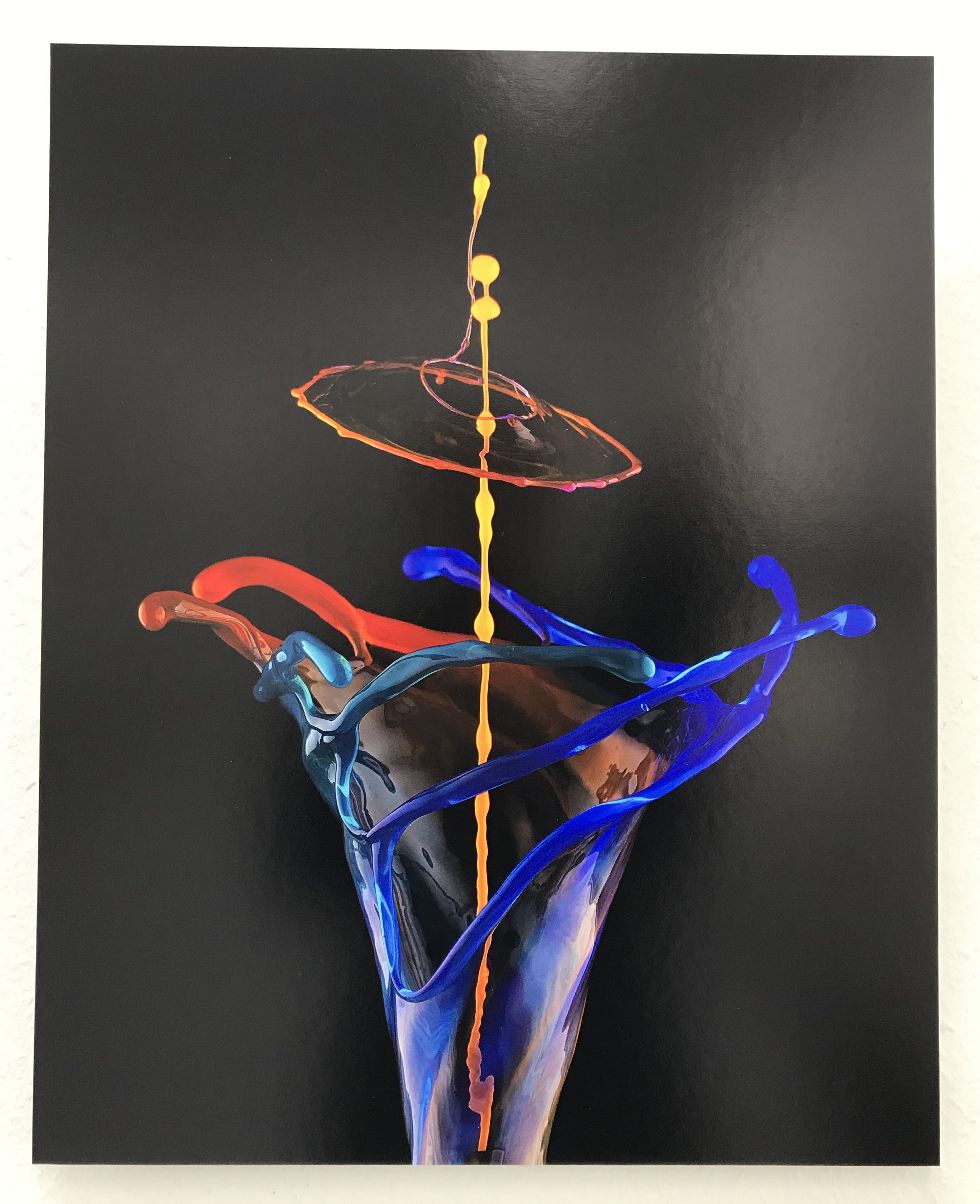

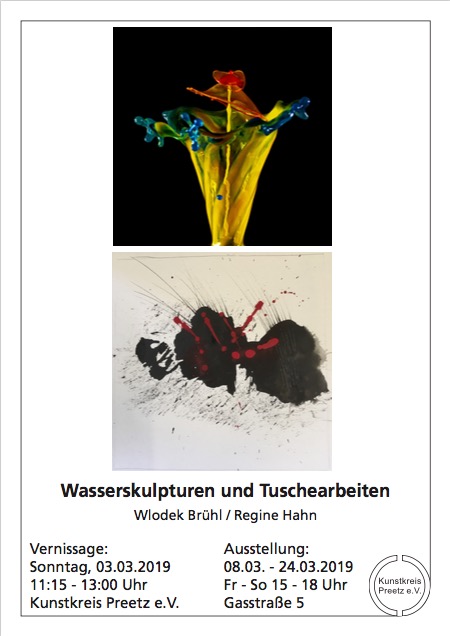

An art & science collaboration with Wlodek Brühl: #dropphotography

If you are here because you saw my title or talk at the Science in Public conference in Manchester and are curious about #dropphotography as a form of art&science collaboration in scicomm — a special welcome to you! If you are here for any other reason — welcome anyway! :-) One of my favourite pet projects right […]

Opening speech for Wlodek Brühl’s art

You might remember that I had the honour of giving a speech at the opening of Wlodek Brühl’s art exhibition back in spring. Preparing my presentation for the Science in Public conference in Manchester next week (that I am immensely looking forward to!), I noticed I never posted the speech. Below is what I sent Wlodek in […]

Vernissage of “liquid art”: The perfect opportunity to combine art & physics to do some scicomm!

If you don’t want to “preach to the choir”, how do you, as science communicator, reach new audiences occasionally? One way that I tried today is to give the (invited, I swear!) laudation at the vernissage of Wlodek Brühl‘s exhibition on “liquid art“. The idea was that visitors would mainly come to the event because […]

Vernissage of water sculpture photography by Wlodek Brühl, with explanations of the physics behind the pictures by yours truly!

I am a huuuge fan of Wlodek Brühl’s liquid art: Pictures of water sculptures that are created with focus on the tiniest of details, that only persist for milliseconds, but that are captured forever in all their fragile beauty. And I think these pictures are an awesome tool in science communication — I see so […]

“Liquid art” by Wlodek Brühl, and how it could be used in physics teaching

Do you sometimes feel that wherever you go, you just happen to observe something that makes you think about physics? I definitely do, and that’s what happened to me again this Sunday. #diwokiel — one week full of exciting events related to digitalization of the world It’s currently #diwokiel, a week-long event on all kinds of […]