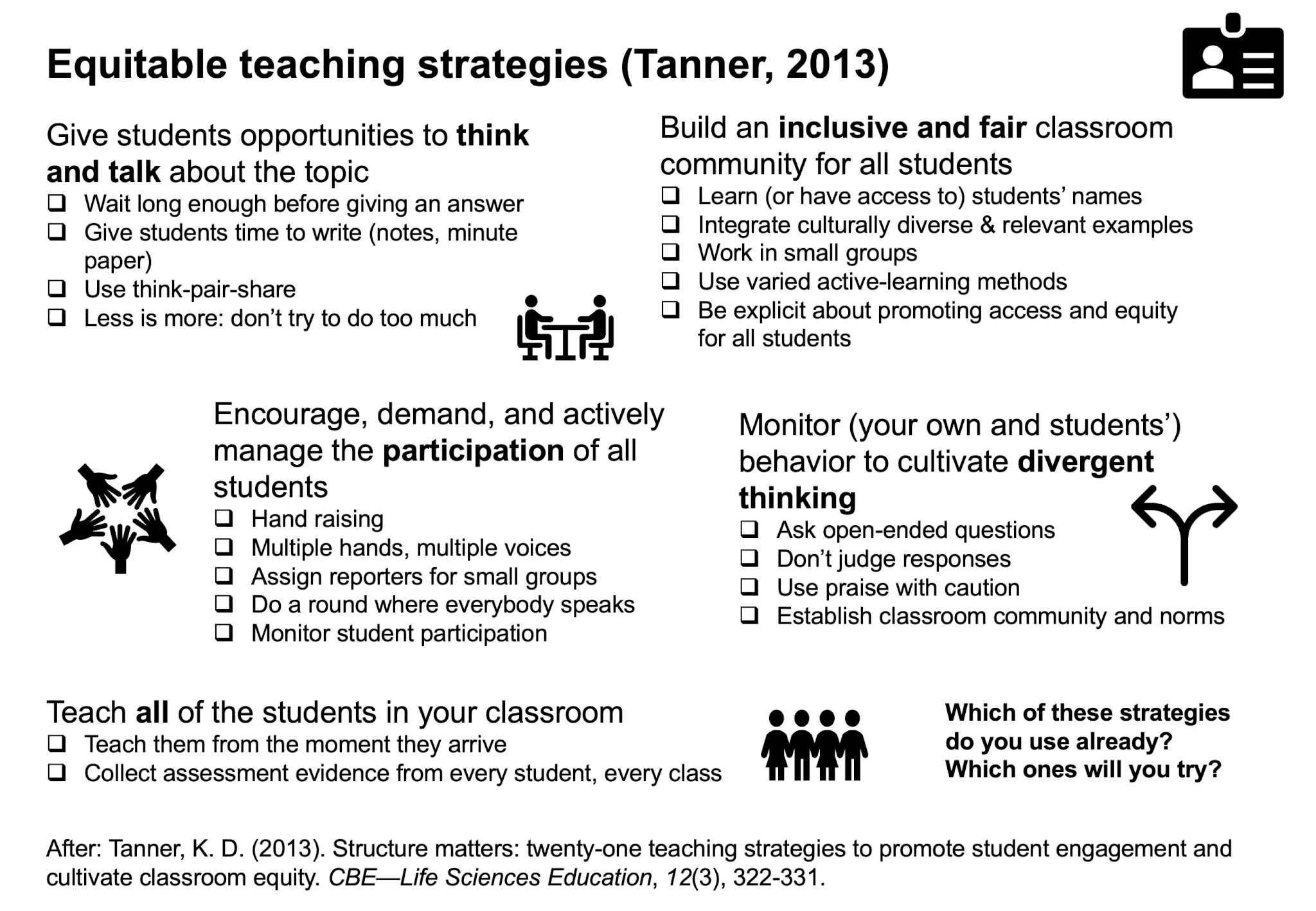

Recommended reading: “Structure Matters: Twenty-One Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Engagement and Cultivate Classroom Equity” (Tanner, 2013)

Teaching for sustainability is about so much more than teaching the content and skills described in the SDGs, or even the cross-cutting sustainability competencies. Today, I talked with teachers who asked what they could do in their courses where the curriculum does not mention anything related to sustainability, and if they should even do anything. […]