Quality assurance at universities is often oversimplified: Single events, captured in indicators that rely on one facet, are met with quick interventions, without any understanding of the complexities of the situation or longer term strategies. This leads to flip-flopping between states, for example getting rid of student group works because students report to not like it, only to reintroduce it when employers note a lack of team-working skills later. Instead, the focus should be on enhancing university culture as a whole, and this relies on understanding a complex system and carefully adjusting variables over time. In this, quality improvement of universities is a wicked problem, i.e. an extremely complex problem that does not have a clear cause or formulation, that will never be “solved”, only dealt with better or not as well, where there is no way to test any of the infinite possible solutions before implementing them, and where the many representations and approaches are all valid depending on underlying norms, values, perspectives, …

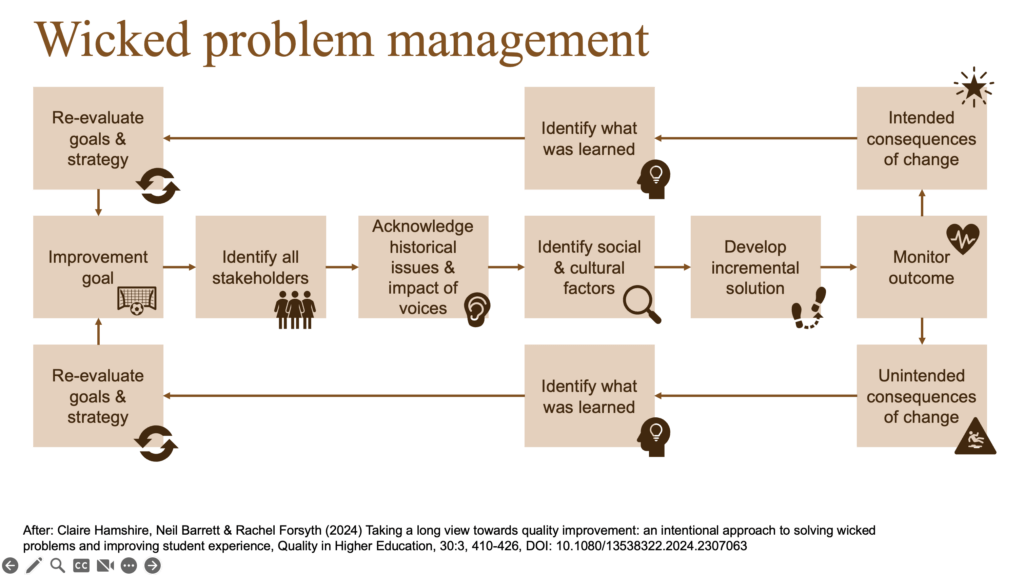

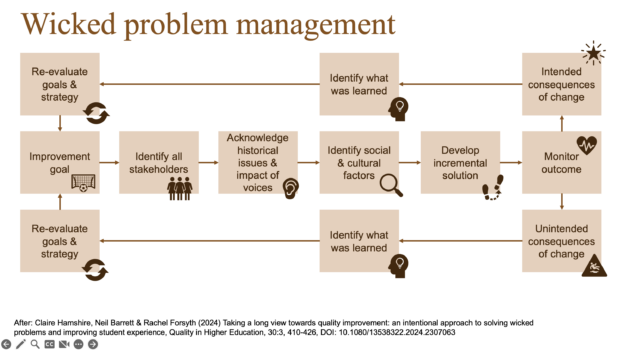

Hamshire, Barrett and Forsyth (2024) present a concatenated approach to quality improvement. They use studies from two strands of research, one focussed on students, the other on teachers, that ran over the total span of 17 years, build on each other and document an iterative approach of continuous learning and refinement of strategies, including all (ok, maybe most? ;-)) stakeholders. Below I redrew their schematic of “wicked problem management” because I want to use it in an upcoming workshop, but it is helpful to keep this in mind when thinking about academic development (or about sustainability). I am sure I have worked with this schematic before when I had my theories of change phase, but I could not find it now…

What becomes very clear is that for wicked problems, there cannot be a quick fix, or one that does not involve all stakeholders, or that ignores the history of the problem, or that does not carefully tests its way forward. It starts as simple as with the difficulty of defining the improvement goal: Quality, for example, can mean anything from “exceptional”, “perfection or consistency”, “fitness for purpose”, “value for money”, to “transformation” (read my summary of Harvey & Stensaker 2008 here). So if the goal is so hard to define already, and needs to be reevaluated at every iteration, it is even more important to make sure that all stakeholders are on board with the process, and are kept in the loop to stay there, too. Also acknowledging the inertia in the system, and that it is due to many factors that may or may not be interacting, is helpful, as is the reminder to really keep changes small and then iterate the process. I think the flow chart above can be very useful to support reflexion on, but also planning of, change processes. I have definitely not always considered all stakeholders or the history of why situations came to be the way they are. And that always backfires…

Claire Hamshire, Neil Barrett & Rachel Forsyth (2024) Taking a long view towards quality improvement: an intentional approach to solving wicked problems and improving student experience, Quality in Higher Education, 30:3, 410-426, DOI: 10.1080/13538322.2024.2307063

Pingback: Different ways students are talking about Wicked Sustainability Problems (currently reading Lönngren, Ingerman, & Svanström; 2017) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching

Pingback: Different ways students are thinking about Wicked Sustainability Problems – Teaching for Sustainability