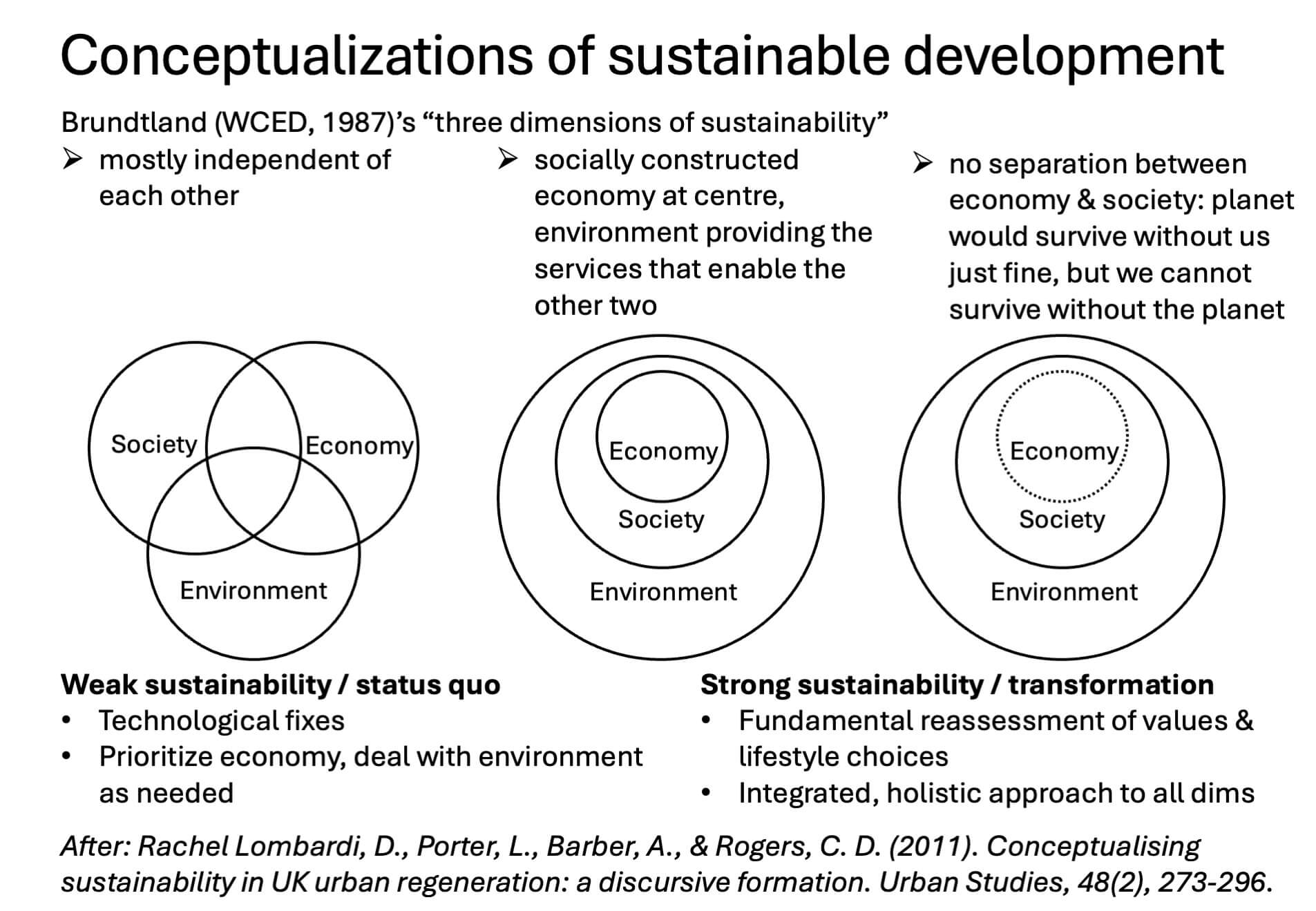

Conceptualizations of weak and strong sustainability (according to Rachel Lombardi et al., 2011)

Rachel Lombardi et al. (2011) write “The overutilisation but simultaneous undertheorisation of sustainability as a term means that it can lend itself to a vast array of very divergent goals“. Or, in other words, as long as sustainability is just a vague buzzword, it is easy to accept, but that is because it is also basically meaningless.

Two of the four misunderstandings about sustainability that Block & Paredis (2019) write about are first that sustainability is about ecological concerns, and second that we need a watertight definition of sustainability. So what I have been doing so far is to point out that there is more to sustainability than just “the environment”, and that getting stuck in discussing the nitty gritty details of what we mean by sustainability is a waste of time, and left it at that. But maybe a better approach is to address that there are different conceptualizations, and that there is a spectrum from weak to strong sustainability, and this is where the featured image of this post comes in.

In the weak understanding of sustainability, the three components environment, society, economy are seen as mostly independent of each other. This is where we mostly maintain the status quo: We don’t need to substantially rethink anything, but rely on technological fixes and prioritize the economy; environmental issues are dealt with as needed.

But then one could also be critical towards the dimensions themselves, as Hine (2023) writes: sustainable development “yoked the pursuit of ecological sustainability to the trajectory of economic and technological development, without any proof that this pairing could pull in the same direction”. So a stronger understanding of sustainability then might see the that economy is socially constructed, but still put it at the center, surrounded by the society, which, in turn, is embedded in the environment, which provides the services that the other two rely on.

A strong understanding of sustainability, transformation, then erases the separation between the economy and society, and acknowledges that “the planet would survive without humanity just fine, but humans cannot survive without the planet“. This means that we need to fundamentally reassess our values and lifestyle choices and approach sustainability in a holistic way.

Interestingly, when googling for “strong sustainability”, I came across many ways the UN SDGs are arranged to match those conceptions: Often they are grouped into the three dimensions with only SDG 17, “partnership for the goals”, in the space where all three dimensions overlap (in different versions, some of the other goals may or may not be in the overlap between two of the dimensions), or arranged as the “wedding cake” where the lowest cake layer is the environment, on which society builds, which in turn carries the economy, and SDG17 as cake topper at the very top. I did, however, not find a graphic that read, to me, as strong sustainability in the Rachel Lombardi et al. (2011) sense. Maybe because the SDGs are really more oriented towards status quo than towards transformation? Rachel Lombardi et al. (2011) show a graphic similar to the one Block & Paredis (2019) also use, mapping out different views on sustainable development on the axes of ecological and social concern. No and very little concern falls into the category of “status quo” (we’ll find technological solutions to fix the issue, without having to change much about the way we live), medium concern is about “reform” (our current systems are not perfect, but we can change them sufficiently to address the challenges), and high concern is about “transformation” (we need to change the way we live and the systems that organize society completely, because our problems “are located within the very economic and power structures of society” and in “how humans interrelate with the environment”). And on this graph, many of the stakeholders like the EU, the UN SDGs, mainstream NGOs, are concerned with both ecological and social reform, but of course not necessarily equally, and not necessarily very much either… I recall using the Block & Paredis (2019) graphic the first time I taught my “Teaching for Sustainability” course but feeling that it led into too many discussions about whether the levels of concern of different actors were both appropriate, and mapped appropriately, or not. But maybe that’s a discussion that needs to happen, at least a little bit, along with the statement that in my course, we deal with a strong understanding of sustainability, which means we assume a high level of concern for both the environment and society, and are looking for transformational approaches?

Rachel Lombardi, D., Porter, L., Barber, A., & Rogers, C. D. (2011). Conceptualising sustainability in UK urban regeneration: a discursive formation. Urban Studies, 48(2), 273-296.