Currently reading Nieminen & Boud (2025) on “Student self-assessment: a meta-review of five decades of research”

There are wildly differing understandings of what student self-assessment can and should do. It can be part of supporting the learning process in formative assessments or as a valuable skill to master in itself to support future learning, or part of measuring learning outcomes in summative assessment.

Nieminen & Boud (2025) conduct a meta-review of 28 reviews of self-assessment studies with a focus on what the dominant discourses are. But even the brief history of self-assessment studies is fascinating: The first one was published 1932 on whether students could estimate the marks they would get from their teacher. Since then, comparing student and teacher marks has lived on, with changing foci on whether student marks could replace teacher marks (1970ies — no, because they weren’t accurate enough and also when used for summative assessment purposes, there is a strong incentive to not report accurately), as an important skill to develop (1980ies), the accuracy of student marks (1990ies — apparently this is the context of the study which resulted in the Dunning-Kruger effect!). Currently, self-assessment is mostly seen in the context of self-regulation and life-long learning.

Nieminen & Boud (2025) find four main ways of framing self-assessment:

- psychological discourse, which describes self-assessment as a clinical intervention with the goal of developing self-regulation skills, done by a neutral researcher expert to a non-expert individual.

- educational discourse, which describes self-assessment as a contextual, relational practice, done pragmatically and in a context to enhance quality of student work, with the students as active agents in the world.

- performance discourse, which describes self-assessment as a (booster of) performance, where the teacher initiates and the students publicly declares their self-assessment for tangible benefits.

- societal discourse, which describes self-assessment as a non-societal practice with the societal purpose to develop responsible citizens and life-ling learners: “Successful self-assessment practices help protect the public from potentially incapable professionals.“

These discourses are quite different and partly conflicting, and “[as] a given discourse limits what can be seen and acted upon in a field, it is crucial to be aware of the compatibility as well as ruptures between various research approaches and paradigms“. I really like that the authors ask us to consider the question “Who has the power to tell truths about student learning?” and call for researchers to relate their research in the context of those discourses to be explicit about their understanding and approach. And I love the framing that “what connects these discourses is care for self-assessment: the will to produce knowledge that in the future might help foster meaningful learning experiences for students“.

The authors end with a discussion of the “self” in “self-assessment”. In all four discourses, the self-assessment is initiated by someone other than the “self”, the student, and with goals that aren’t necessarily aligned with the student’s own goals, based on ideals that are also not necessarily the student’s, and that might not even be explicit. Coming back to the question about who gets to tell truths about student learning, that power is most often not with the students themselves, or at least not on their own terms, yet. And that is the direction in which research and practice should develop!

Nieminen, J. H., & Boud, D. (2025). Student self-assessment: a meta-review of five decades of research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2025.2510211

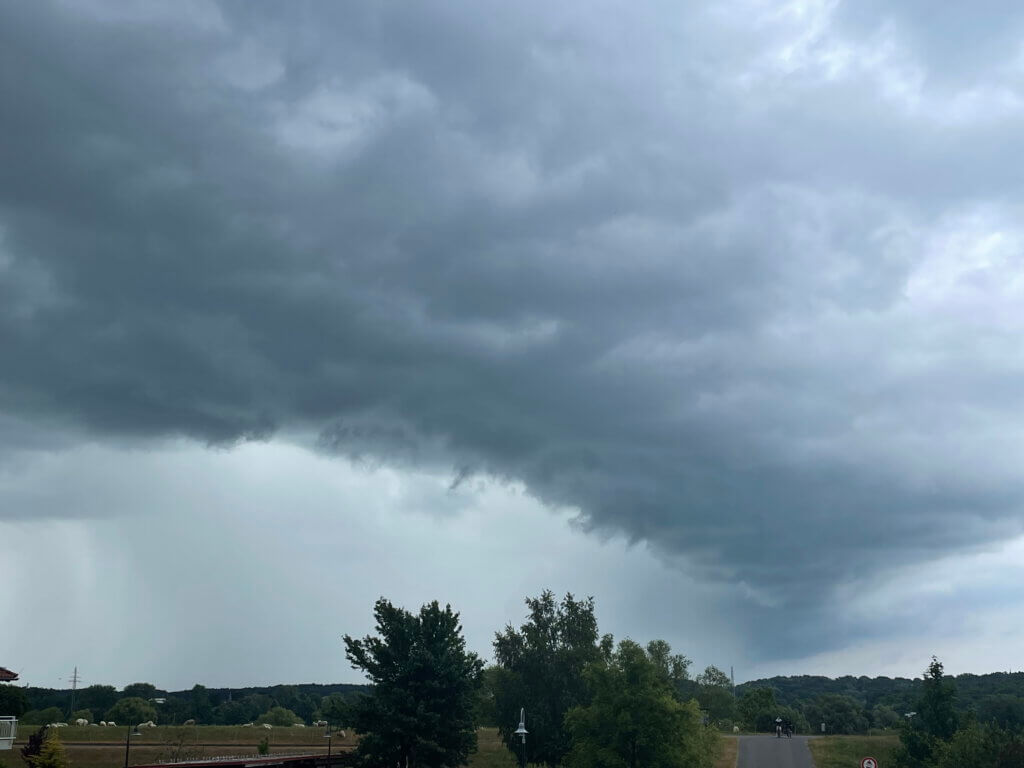

Cloud and sheep watching on the Elbe dikes last weekend…