Ice watching and thinking about reflections — in the water, and in Harvey et al. (2025)’s article

Climbing the steps out of the water after an ice dip lets me see the world from a different perspective. Instead of focussing on not slipping and on controlling my breath on the way down, on the way up I can linger, observe, and document. Building such small (or larger) moments into life and work, to see the world in unexpected ways and to make sense of what I see is sometimes really easy, but often requires a lot of effort to prioritise over seemingly more urgent, louder tasks. In that, it is very similar to making time for reflection. Both activities are extremely valuable, both in the moment and in their cummulative effect over time, but need to be prioritized.

“Reflection is a deliberate and conscientious process that employs a person’s cognitive, emotional and somatic capacities to mindfully contemplate on past, present or future (intended or planned) actions in order to learn, better understand and potentially improve future actions” according to Harvey et al., 2016. Related to learning, we want to reflect for several reasons. For academic learning, it is about connecting theory to practice, new knowledge to older knowledge, new impressions to old assumptions. One way to do that is through journaling (or blogging ;-)). We could also reflect to develop metacognition — understanding how we think and why — and to contribute to lifelong learning.

Above, you see ice floes that have been pushed together and ice spikes pressed upright by the colliding edges, and then there is interferences of wave fronts on the ice where it gets flooded by water as I move, each front with a handful of waves following tightly behind in the very shallow water layer on the ice.

In “Reflecting on reflective practice: issues, possibilities and guidance principles”, Harvey et al. (2025) suggest eight principles for scholarly reflective practice for learning and teaching:

- Learn how (to reflect). Reflecting can be learnt, and it can be taught. Before teaching it, though, teachers need to learn and practice it themselves, and then role model and facilitate it in their teaching

- Make time (to reflect). Reflection takes time, and we need to make time for it, both individually and in groups. Some formats for reflection are relatively quick and can easily integrated in teaching, e.g. minute papers. Others, like journaling take a bit more time, but can also become a habit (case in point: this blog)

- Set the scene. If we are using reflection in teaching, we need to make sure students know why we want them to reflect, but that they can always choose to opt out. Especially when using methods that require closing our eyes or something else that students are not used to in a classroom setting, we also should give them a trigger warning of what they might experience.

- Scaffold. Start easy and then build on it.

- Practice and experiment. Find community to learn from and with, whenever and wherever you prefer.

- Offer multiple modes. Reflection can be artistic or analytical or both, and we should give students the option to experience several ways and ultimately choose one that works for them.

- Assess with care. Assessed reflection is not necessarily genuine; in a surveilled space we are “encouraging performativity”. The advice here is to “never assess raw reflections but, if assessing, do so respectfully and allow meta-reflections where learners have reflected on their documented reflections and synthesised their key learnings”.

- Be scholarly. “In practice, this means being informed by research and providing evidence for all activities”.

I like these principles, they intuitively make a lot of sense to me. I like the focus on a caring approach when teaching reflection in 3, 4, and 7, but I also really take a lot out of it personally with regards to practising reflection (both as in doing it regularly, and as in putting effort into improving the skill), experimenting with multiple modes and in community with others, and making time for all of it.

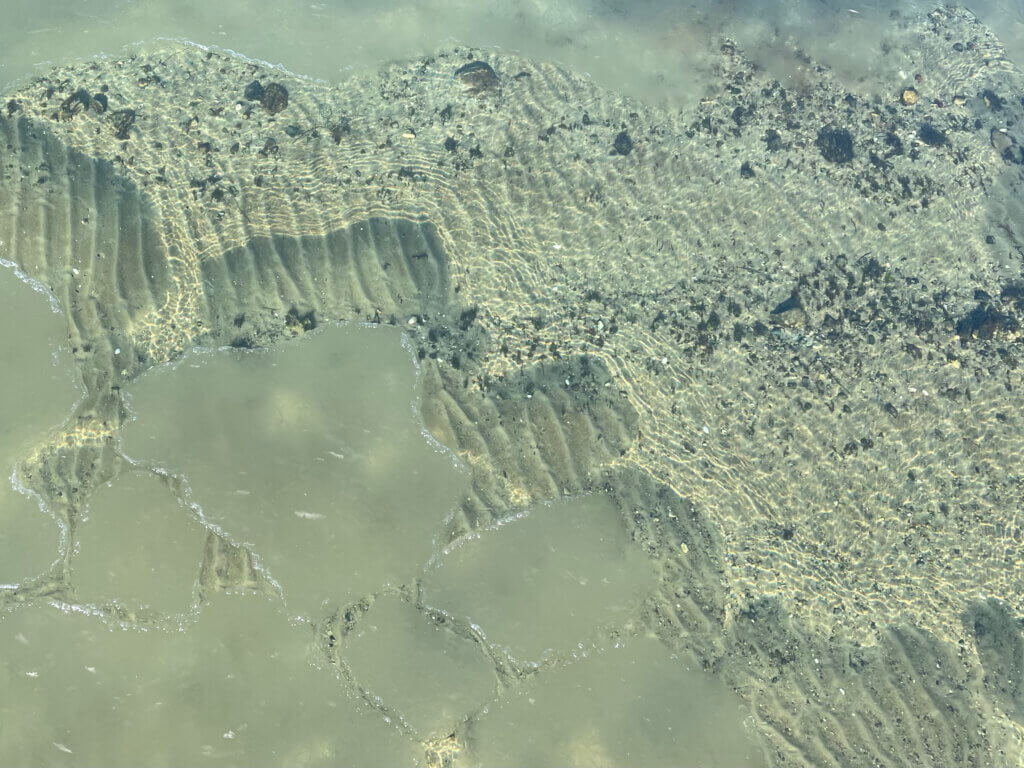

Like I make time for my wave watching: Below, you see ice floes floating on water. A part of the non-covered sandy seafloor is shaded, so you clearly see the ripples in the sand, and the rest shows a pattern of sunlight refracted by the surface waves.

In contrast to the picture above, where the wave field that you see in the light and shadows of the waves seemed to be mostly shaped by the wind, below we see a different gap in the ice cover where there are much fewer and smaller waves, and they seem to follow the shape of the ice edges at the bottom of the image. Here, the ice is moving and radiating the waves!

And here the ice cover is mostly closed, and if you look carefully, you can see finger rafting where two sheets of floating ice collide! (clearer pictures in this old post from Oslo)

If this wasn’t the best day to take some time, go ice dipping, enjoy the snow, the ice, the sun, I don’t know what a better day would look like!

Harvey, M., Walkerden, G., Semple, A., McLachlan, K., Lloyd, K., & Bosanquet, A. (2025). Reflecting on reflective practice: issues, possibilities and guidance principles. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2025.2463517

Reading "Distributed leadership and peer review: a MOOC exemplar" by Bosanquet & Harvey (2005), and checking out their MOOC - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] experience. Now I really want to work with that! And in module 8 on “reflection” (and reflection is the link to how I came to read this article and find the MOOC in the first place…), they […]

Weekly Resource Roundup – 18/2/2025 | says:

[…] M. S. (17/2/2025), Ice watching and thinking about reflections — in the water, and in Harvey et al. (2025)’s articl…, Mirjam Sophia […]

Crynodeb Wythnosol o Adnoddau – 18/2/2025 | says:

[…] M. S. (17/2/2025), Ice watching and thinking about reflections — in the water, and in Harvey et al. (2025)’s articl…, Mirjam Sophia […]

Marina Harvey says:

Dear Mirjam,

Gosh, that was fast!

Thank you for writing about the principles in this lovely blog.

Cheers, Marina