Currently reading Venet (2024)’s “Becoming an Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School”

I’m continuing my reading of Venet (2024)’s “Becoming an Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School” (online access for LU!). I first wrote about the first couple of pages here. In a nutshell, my main take-away then was that “the process is the point”. We cannot achieve healing and justice in school (which is what Venet writes about), or a sustainable future (which is what I am thinking about) if the process doesn’t match the goal. That is because the goal is emergent — we don’t know what a just school or a sustainable world looks like — so we need to find our way there by acting in alignment with what we hope the goal will have achieved. For example, if we want to be an inclusive university, we have to start making all meetings discussing strategies of how to get there accessible already. We have to include the voices that we usually talk about, but don’t listen to, already now in the process, not only in some distant future when we might have figured out how to do it. The process is the point.

So here are some more notes as my reading continues.

One thought that felt eye-opening to me and where I felt a bit called-out is on the danger of saviourism. Wanting to do “more” and “better” than what a person or community actually needs and asks for pushes them into the role of having been “rescued” and having to be grateful for getting something that might actually not only not meet their needs, but that might even create more work for them, both in terms of emotional work of having to respond to something they did not actually want, and also in practical terms of dealing with what they got in the end. “When we swoop in with the “fix” rather than listen to what people need, we undermine trust and further remove people from their sense of agency and control, which can exacerbate a trauma-influenced sense of powerlessness” (p62).

Another thought was about procrastinating on projects in response to un-processed trauma — like for example living through a global pandemic. Sometimes we have to “try to meet the moment rather than trying to control it” (p62). We are working with emergent strategies and solutions, so we cannot set SMART goals for all the steps of the way and expect to be able to meet them — because the steps cannot be predicted and planned; because we need to expect the unplanned. We need to recognise that “there are “multiple paths up the mountain”. When we try one path and find it blocked by a fallen tree, we adapt and find a new way. Other times, the best bet is to turn around, return to safety, and reassess for another day” (p63). So the Venet suggests a different alternative: “What if we built systems that celebrated our need to pause, rest, and take breaks, rather than viewing these as impediments to a “timely” process? What if we found a way to capture the explosions of inspiration and innovation and use them as fuel for change? And how might we swim together, each responsible for our own movements yet moving together as one?” (p64)

Another important thought is that we need to dream up a vision of what we want to achieve, for example a joyful school that students want to attend. If we just define the goal in terms of student attendance, anything as simple as a flu wave can make it seem that we are failing at the goal. Goals are easily described as deficits that need fixing, but a vision is bigger than just fixing individual problems. A vision can and should go beyond the frames we are currently working in, and does not need to seem achievable even within our own life times. The process is the point: how would we act now if we were already living in the vision we just developed?

Sometimes (all the time, really), we encounter goal conflicts. The example given in the book is a teacher who gets overstimulated easily, and a noisy class that they are disciplining more strongly than aligned with their vision. Here, Venet suggests the “both/and” approach. Instead of deciding which goal or need to prioritise (“either/or”), we ask ourselves “how can we honor both x’s and y’s needs?” This makes the world more messy, but also challenges our creativity to come up with solutions that lead to growth. Binary thinking is unhelpful and a tool of oppression, think for example a fixation on binary gender vs a spectrum. Black and white thinking is also in itself a trauma response, reducing complexity to a level that seems manageable (but at the same time clearly counterproductive to constructive solutions). In the example given in the book, a solution for a similar situation with a different easily overstimulated teacher and a lively class is co-created: the teacher dials back on the discipline and the students learn about the teacher’s experience and help self-regulate in order to support them. Co-creation at its best!

In another example, Venet describes how we can work on both the system and the individual simultaneously. The system does influence individual behaviour through culture, but individuals have agency, are capable of growth and can change, as can the system.

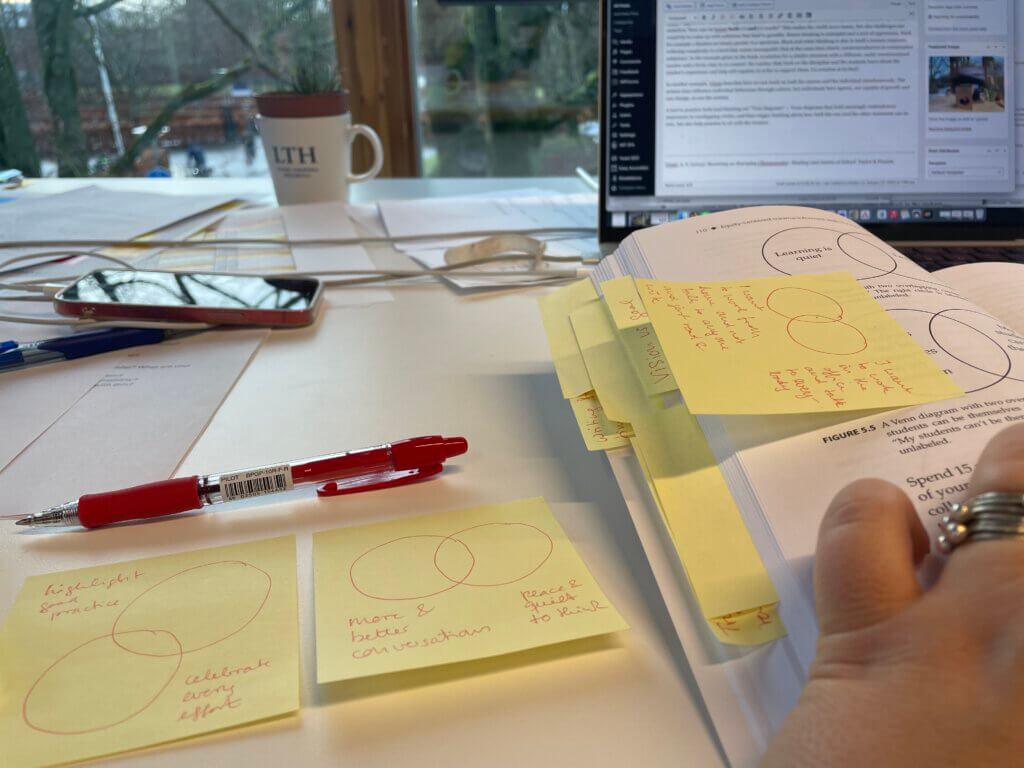

A tool to practice both/and thinking are “Vent diagrams” — Venn diagrams that hold seemingly contradictory statements in overlapping circles, and thus trigger thinking about how both the one and the other statement can be true, but also help practice to sit with the tension. Here are some of mine: I want to have both more and better conversations and peace and quiet to think. I want to both highlight good practice and celebrate every effort.

Sometimes I find true co-creation really difficult. In the next chapter, Venet talks about how “my way or the highway” thinking harms relationships, and how “if we’re aiming for a vision of true community in schools, we have to get there by being in community along the way” (p111). Maybe that is a case of “I want both co-creation of inclusive behaviours and results right now”, and also a case of saviourism where I assume that I know what is needed without actually involving everybody to figure out what really works for them. There is a tension also recognised by Venet in what it then leadership in education means. It is easy to fall into transactional approaches where teachers or students are “mined” for ideas without engaging in actual relationships with them, when instead we need to see ourselves as “nobody special”, but engaged in a web of relationships. If we see ourselves as one person in a web of relationships, we “can tap into the collective power of countless others who also want change” (118).

A similar tension between wanting good results and the impatience of getting them is described in the next chapter, “slowing down”. Equity work is urgent and we need to slow down, to become aware of what is going on and prevent harm coming from acting too fast. “Staying in a rush when making change can backfire, even when our change goals are admirable. When we rush, our minds use shortcuts to help us be efficient. This is where our biases and stereotypes can come out in full force, because if you want to make a very quick decision, context slows you down.”

Slowing down is a mindset shift, not just an action (and one that I very much need, too!). “If we want to give students a break from the unrelenting pace of perfectionism, we have to model a different way ourselves”. Ouch, that hits home! But Venet offers helpful thoughts:

- Thoughts like “”I can’t rest because I haven’t done enough” [..] are often bound up in racist, ableist ideas of what it means to be of value as a human” (p131). Our expectations of “how long things take” are based on what, really? Some idea of how minds and bodies should work. Instead, we should work at the speed that our own body and mind can do, no matter how that matches external expectations. We can individually move at different speeds, but through our network of relationships, collectively respond to the urgency of a situation. “This affirms our commitment to changemaking that values everyone, rather than prioritising only those who can keep up with a certain pace of work. As we align our changemaking process with our values, slowing down helps us with the true inclusion we hope to build as we work towards justice” (p134).

- We can easily integrate physical reminders and cues in our environment (in their examples little animal figurines) that remind us that we want to slow down. What could be in my line of sight in many situations to remind me of my commitment to slow down and so that “taking a moment to pause and check in can align us with or vision or help us situate our actions within the wider web of our networks” (p135)? I will think about that (Right now, I have a time turner on my desk lamp, and a dragon skeleton, neither of which seems to be particularly helpful here, and the time turner even very much counterproductive…)

- “Urgency and deliberate slowness make the walk toward change more steady, happier, and smoother” (p136), like it is easier to carry a bucket in each hand while walking slowly, than walking faster with the lighter load of just one bucket in one hand… And “however you choose to slow down, remember that no one else is going to give you permission to do so” (p136).

But not every act of slowing is helpful, much like slamming your breaks on the highway is not. If we slow down, we should be doing it with intention, for example to dream and vision, to wonder, to be relational, or to feel. This is a really helpful thought for myself, to give myself permission to slow down with intention (because “just because” still feels weird, haven’t fully processed and taken apart the ableist idea behind it), but it can also be integrated in team meetings to slow a group down to dream and vision, wonder, be relational, or feel.

The next chapter is about “working from strengths”. The very first thought in this book that I read was about how blogging from bed can be an act of activism, and even though I am writing this at my desk at the office right now, it felt so empowering to see acknowledged that not only the public speaking part of my work is a valuable contribution to change.

Now we have reached the moment where I really need to slow down to think, and that is thinking about how different ways of influencing change make me feel. Since this is my blog and you can always skip reading it, I’ll share those thoughts below. This will be the last part of this blog post, for the next part of the book’s summary you will have to find the next blog post on that!

So here we go: A list of ways of influence suggested in the book, and my thoughts on what they mean in my practice and how I feel about that.

- Direct action: Just changing something within my power, like bringing porcelain mugs to workshops and hand-washing them (instead of using the paper cups the caterer uses). Maybe that example is too small? I do write a lot of emails, for example to caterers on campus when then don’t live up to the promises on their websites or the university policy to cater only vegetarian food. Also small, but at the same time very easy to implement. I do include questions of sustainability in all my teaching, no matter whether it “should” be there or not, just because I can… It feels like direct action is an area to explore more. It is really hard to get rid of someone on a permanent position, so why not use that for good…

- Advocacy: Making myself heard on behalf of others or myself. This does not feel comfortable, maybe because it seems to imply public speaking, which I HATE.

- Modeling: Be the change you want to see in the world so others can see what it would be like. I feel like I do that sometimes, for example by talking about sustainability in every context, not just where people would expect it to come up. And I try to model behavior by bringing said mugs, taking the 2 day train trip rather than 2 hour flight, … And I think modeling behavior like not obeying in advance is really powerful, both in the act itself and in modelling it for others.

- Questioning: Asking the hard questions or bringing unheard perspectives. This way of influencing makes me feel excited! It is a bit like advocacy, except inviting people into dialog so they can reach their own conclusions, or maybe even better, we can reach a shared one. This I definitely want to do more of now that I am aware that it is a thing!

- Coalition-building: Building relationships of like-minded people to make change together. I feel like that is what I do a lot of the time and what comes natural to me anyway. I do that for my own support network but also for networks where teachers support each other, mostly without me.

- Disrupting: Doing something different knowing it will ruffle feathers. Ehm, ja, that sounds familiar.

- Creative non-compliance. Not following along with harmful practices but doing so under the radar. This seems like fun to explore :-D And also like an easy first step before then coming out into the open with it and starting to model the changed practice.

- Experimenting: Trying something new as a way to get started with change. Always!

- Observing and documenting: Keeping a record to observe patterns and hold others accountable. Definitely an area I can improve in, having records is often so useful!

- Amplification: Boosting other’s voices, especially those with less power. We try boosting others’ voices for example by inviting people to write about their good practices on our Teaching for Sustainability blog, or by inviting them to speak at seminars and conferences, but in both cases it is their own voice that we try to give a bigger platform and wider reach to. It feels like it would be a slippery slope into saviourism to try to speak for others, only louder…

- Supporting: Finding out who’s already doing the work and pitching in to support them. I try that, but it is sometimes really difficult to find those groups! And then I also have an idea of what I want to achieve and how, and if there is a misalignment about the how, I find it very difficult to engage (yes, thinking about concrete examples here). But at the same time, this probably leads to me re-inventing the wheel and also general waste of energy if things happen in parallel rather than together.

- Facilitation: Helping others communicate and collaborate. That’s kinda my job in a nutshell. Feels good to recognize it as a way to contribute to change!

Venet, A. S. (2024). Becoming an Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School. Taylor & Francis. (online access for LU!)

Slow reading of “Becoming an Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School” by Venet (2024), Part II - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] wrote about some more thoughts on Vent diagrams when I first read the book, but for this summary, maybe the main point is to extend an invitation […]

It is not up to us to complete the work, but neither are we free to desist from it - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] in School” (where I understood that “the process is the point“, and where then helpful tools like “Vent diagrams” were introduced). Now, reading the third part of the book felt so empowering. The Talmud quote that […]

My learning diary for the MOOC "Paths of transformation: sustainability in higher education" - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] I should take more time for… breaks. See my last post on slowing down. Was it really a good idea for me to binge this course last night after and on top of a full day of […]

Podcast recommendation: The Broken Copier! - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] Luther’s BlueSky that stuck with me. It was something related to his slow reading of “Becoming an Everyday Changemaker“, and reflections on that and how he applies it to his own teaching. I then ordered the book […]