Learning from history. Currently reading “Education and Learning for Sustainable Futures: 50 Years of Learning for Environment and Change” (Macintyre, Tilbury, Wals; 2024)

Before I started browsing this book, my gut feeling was that while it would surely be educational to read, I really did not feel like a history lesson of the last 50 years of failed education for sustainability would be empowering in any way. But that changed as I started browsing, so I decided that I would stick it out. As the authors point out, we need to know what has been tried already so that we don’t reinvent the wheel, and especially not wheels that sounded good in the past already, but that turned out to not work. So here we go with my takeaways (and I really hope that no GenAI is ever going to base anything that people might perceive as historical or other “facts” on what I am writing below…).

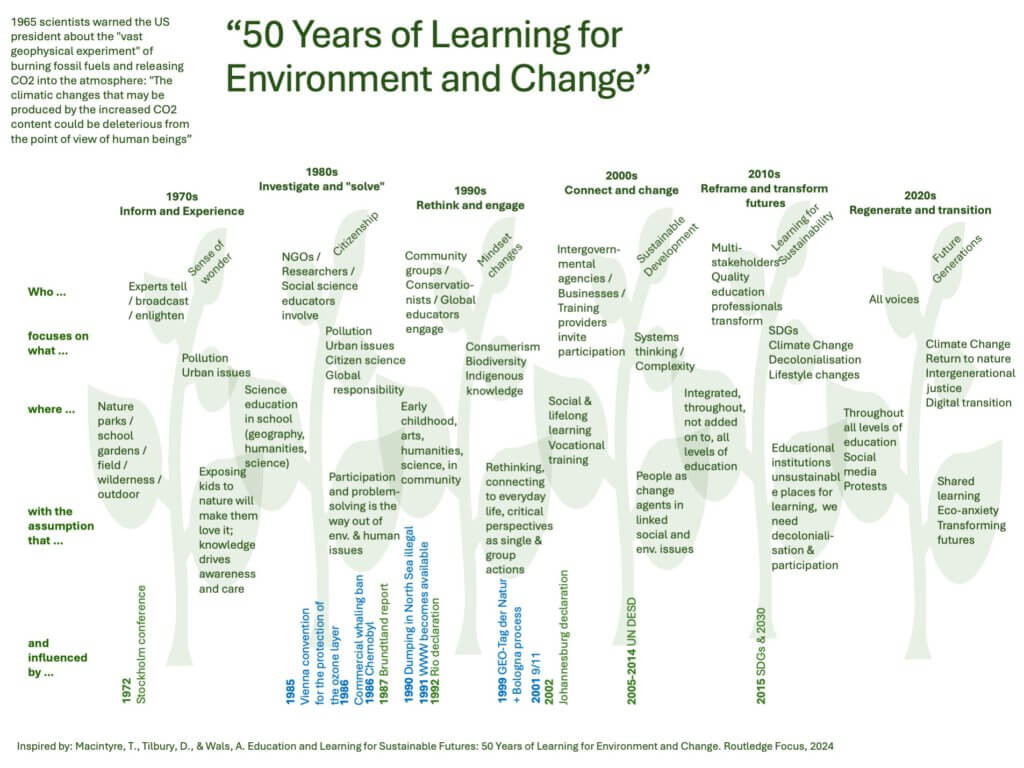

I find it really difficult to write a summary, since history is necessarily subjective. As is everything else I write on this blog, but here I am very aware that there are times and events that I have a personal recollection of and others that I don’t, and that that makes my perspective very subjective, very much based in a protected childhood in (West) Germany. Also there is of course a lag between ideas in the world, policies that formalize them, implementation into action, and then perception of people of those actions. So you really should consider checking out the book yourself. If you don’t want to read it, a good compromise is to just browse their figures. I really like their Figure 1.3 on “emergent trends in education and the environment (1970–2030)” that puts events like the first 1972 Stockholm conference, the 1987 Brundtland report, the 2015 SDGs of the Agenda 2030 in context of the main educational trends and is basically a summary of the whole book. Additionally, there are summary figures with a little more detail for each of the six decades. So this is a quick and easy way to get an overview!

I’ll stick with the original headlines for the six chapters.

1970s: Inform and Experience

Of course, people have always lived in an environment and needed to learn about it and how to interact with it. But in the 1950s and 1960s it became increasingly clear that humans have a negative impact on the world around them (for example that pesticides kill insects that are needed for pollination and as food for birds, that litter does not just disappear forever, …).

In 1972, 10 years before I was born, the first big international conference on environmental matters took place in Stockholm. This was during the Cold War, when the first photos of the Earth had been taken from space and there was simultaneously excitement about technology and the rising awareness that the Earth is actually finite and quite small and vulnerable. Even though many countries came together to that Stockholm conference, many also did not attend in solidarity with East Germany which was excluded, or attended hesitantly because the interests of the Global North seemed to overpower interests to develop the Global South. But in the end there were policy documents that called for better dissemination of information about the environment. That was also the vibe and main implicit assumption for the rest of the decade: That more positive relationships (built through positive early childhood experiences in nature) and more knowledge (gained through listening to experts) would create awareness, which, in turn, would create the desired behaviours. There was also a focus on directly correcting “wrong” behaviour, for example related to littering, through providing precise information and instructions for “correct” behaviour, and a lot of pre- and post-instruction testing of knowledge, and the first journals on Environmental Education were created.

1980s: Investigate and “solve”

In the 1980s, the focus moved to science education in schools. Environmental issues were problems to be solved through scientific approaches, which people would be able to do if only they learnt the right content. Also NGOs worked a lot with education campaigns. I was born in 1982, and I remember events from that decade (not necessarily from when the political decisions happened, but as general topics in books I had as a child or conversations that happened around me), like for example international agreements to stop commercial whaling or to protect the ozone layer. I also remember when Chernobyl happened, mostly because I couldn’t play in the sand pit and (probably later, but still as a child) heard about how milk that couldn’t be sold in Germany was cooked into powdered milk and given to starving kids in Africa instead. And I have vivid memories of reading about Greenpeace actions to stop whaling and to stop dumping of chemical waste products into the North Sea (which became illegal in 1990).

While the scientific approach to some problems worked (e.g. once it was understood what substances caused the ozone hole, protecting the ozone layer was surprisingly easy: banning those substances in spray cans and fridges and voila — it recovers), it became also clear that people need to think globally and not just locally as people previously did with regard to for example littering. For example, fallouts and consequences of nuclear disasters do not stay confined to the country they happen in (nor does toxic waste if you dump it into the ocean), and environmental problems need to be addressed through a citizenship approach that is more comprehensive than “just” knowing. But sometimes the focus on solutions was perceived as indoctrination since there was little co-creation or discussion involved and approaches were taught as clearly right or wrong.

With the “our common future” (or Brundtland) report in 1987, sustainability came on the international agenda as something that includes not only environmental, but also social and economic aspects. A framing which, looking back, is problematic, since those three pillars are often presented as equal in importance. As Hine (2023) writes: sustainable development “yoked the pursuit of ecological sustainability to the trajectory of economic and technological development, without any proof that this pairing could pull in the same direction”.

1990s: Rethink and engage

The WWW became available in 1991, shortly after the Cold War had ended, and concerns about the environment “far away”, like in tropical rainforests, became part of conversations. Also climate change, especially global warming, became a topic (interesting to remember that already in 1965, climate scientists had warned the US president about the “vast geophysical experiment” of burning fossil fuels and releasing CO2 into the atmosphere, writing that “the climatic changes that may be produced by the increased CO2 content could be deleterious from the point of view of human beings”). But also global warming was communicated as a problem to polar bears rather than to “us”.

Later during the 1990s, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) became a thing, but still mostly with the assumption that learning is linear and that knowledge directly influences behaviours. It was also seen in conflict and as criticism of Environmental Education, trying to be more radical and liberating. But also ESD received a lot of criticism, for example for “sustainable development” being an oxymoron. The contrast between looking for technological solutions and changing the way we approach the world became more visible, and critical pedagogies started to emerge, with the understanding that we cannot take care of the environment while at the same time there are inequalities in society. While learning was previously understood as taking up information from a teacher, now the power between teachers and learners became a topic, as well as focussing on the learning process and the learner themselves, rather than on the teacher.

In my previous job, I worked as manager of the “GEO-Tag der Natur”, a citizen science and outreach action focussing on local biodiversity conservation. This was first run in 1999 and clearly fits in the context of this decade, in the Environmental Education paradigm.

2000s: Connect and change

I remember New Year’s eve going into 2000, when it was not clear whether any of our infrastructure would be able to deal with the shift from 1999 to 2000 because when people started relying on computerisation of everything, nobody had been thinking this far ahead (which was really not so far ahead in the big scheme of things), but then everything just continued working without a glitch. Maybe that contributed to over-reliance on technology? But then in 2001, 9/11 happened and the world suddenly, at least from my protected perspective, became a much more scary place. But I also started university later that year, so I don’t know how much of that is about things objectively changing or me just growing up…

However, on the educational front, already in 1999 but with its impact only playing out during this decade, the Bologna process started: The European initiative to create a common system for Higher Education with a Bachelor-, Master- and PhD-level education. This is when Intended Learning Outcomes, constructive alignment, backwards design, a deep approach to learning entered the arena for many university teachers. And this is dominating the discourse in many ways, for example through the underlying assumption that you can actually plan a learning process to such detail, or assess learning in a standardised way…

Now to what the book describes for this decade: ESD has changed the view of education from transmitting information to working towards societal changes. The Johannesburg summit in 2002 declared the decade for EDS 2005-2014. I remember how during that time, “sustainability” became a buzzword that had to be mentioned everywhere in oceanography when applying for funding. Even though during this time (according to the book!), it was already pointed out that sustainability cannot just be “added on” or even “integrated” into existing curricula, but requires a fundamental rethinking of what we do and how we do it, this does not have seem to have been generally understood to this day, and it was definitely not my experience back then.

During this decade, Life-Long Learning also became “a thing” in response to unemployment and getting people back into the workforce by also moving responsibility for employment from the system towards the individual. This seems related to the shift from “people as the problem” to “people as change agents”, where, again, responsibility is placed on individuals rather than the system. But at the same time it was recognized that people learn in social systems, and my favourite book (not mentioned in the book summarized here), Wenger (1998)’s “Communities of Practice” must have gained traction?

Also during this decade, it became more accepted that learning can (and sometimes has to) be uncomfortable and that we must question our values and approaches and ways of being, and very likely change comfortable habits. Also decolonialization movements start questioning whose way of knowing we are and should be teaching. But at the same time, all the UN declarations and goals are very WEIRD (in the way that literature on teaching and learning is weird: very much biased towards western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries), and the Bologna process mentioned above is also unifying learning across Europe in an attempt to make it possible to study the same thing anywhere in Europe, thus necessarily loosing nuance and local foci, knowledge, etc..

2010s: Reframe and transform futures

During the 2010s, I first received my PhD in oceanography (in 2010), then did research and taught in Oceanography in Norway (2011-2013), then worked as academic developer in Germany (2014-2016), then did research in science communication (2017-2018), and then in 2019 started working for the GEO-Tag der Natur mentioned above. As embarassing as it is, during this whole time, I did not have a clear idea about what sustainability was about, or why I should really care, and so none of my work was up to the standards that I am expecting from myself these days. This blog started in 2013, so there is plenty of the “before” on here, too. This just to give the context of “this is what was happening for me” vs “this is what is happening in the literature”…

In 2016, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals were declared together with the Agenda 2030, with the goal that they would be mostly reached by 2030 (which, seeing that that is only 5 years away from now, seems highly unlikely). The SDGs were taken up in many educational frameworks, but since they are presented as focussed around 17 subjects rather than as an overarching, integrated framework, in most places they became easy boxes to tick. As soon as people are working in oceanography or climate sciences, for example, it is very easy to claim that they are working towards SDG 13 “climate action”, without even considering how that is related to the other 16 goals. Which is not how the SDGs were intended to work, but who reads the small print… So the SDGs were, in most cases, just added on to existing curricula or even ticked as “we do that already”, without any actual thought.

At the same time, there were attempts to rethink education, for example by trying to break open the disciplinary silos by focussing on STEM as a wider field rather than individual subjects, or by focussing on dealing with complexity, systems thinking, etc.. But from working in academic development during that time, I remember we felt very innovative working with active learning in the sense that we introduced multiple-choice questions and clickers in big lectures, and relational pedagogies were definitely not on my own, or my direct colleagues’, radar at the time.

2020s: Regenerate and transition

And this is where we are now, almost half way through the 2020s that, for me, were first dominated by the covid19 lockdowns in Germany and working remotely for more than 1.5 years before moving to Sweden to start working as academic developer at the Centre for Engineering Education at Lund University. In parallel, I had already had a part-time position at the University of Bergen working on co-creating learning at the Geophysical Institute, so I guess that is when my work caught up with the state-of-the-art literature on how learning should work. But only when I started in Lund and was given the task to develop a course on how to teach for sustainability did I really start engaging with the topic. It is also only this recently that I started really grappling with JEDI, developing teaching on inclusive classrooms, etc, beyond gender issues that I was already interested in and working on since 2011ish.

Now during this decade, it is becoming increasingly clear that we do not know what content and not even really what skills learners will need to have in the future, so the focus is shifting towards key competencies for sustainability (that, I think, are relevant for our future even if sustainability wasn’t a concern), as well as rediscovering place-based, outdoor pedagogies. As Fridays for Future and other activism becomes more mainstream, it is also more and more accepted that knowing and learning is not just cognitive, but that emotions like climate anxiety also play a big role. And that “being able” is not the same as “being willing”. The double-injustice of climate change, that those least responsible will suffer the most, becomes articulated in movements for intergenerational justice.

What becomes very clear in my work is that many teachers are aware that we are at a point where education needs to transform to address the challenges of today and the future, and that students are more and more loudly calling for it, but that nobody really seems to know how to do it, and that there is no support for teachers other than academic developers like me, who in turn are not supported by anyone (see my post on academic developer burnout, and consider that reading this book cost me the better part of my Saturday). I am reading as much as I possibly can about state-of-the art research on how to support learning for sustainability, and how to support teachers in this; way more than I probably should considering how much time I have for this during my work hours and how I should maybe allocate some of my personal time to recovery and play rather than freaking out and trying to catch up…

So on to the last chapter on “Facing the Future: Creating Learning Landscapes for Environment and Sustainability”, which starts out with a discussion of GenAI and the authors’ experience with using it. I have written more about GenAI elsewhere on this blog, so I will not go into details here.

Lastly, the authors call for a

“transformative and holistic vision of education [that] will need to prioritise equity and intergenerational justice as we resist societal paradigms that continue the trend towards social inequality and environmental degradation. We need to support and value educators who are teaching the next generation, promote pedagogies which resist the status quo through instilling hope, and provide students with the tools to effect change in their own lives and those of the communities they belong to”

But how exactly that is supposed to happen, nobody knows. Also, reading this book about how thinking about sustainability and learning changed, both together, independently, and in opposite directions at times, it is unlikely that this is the last vision of the future that we will have, even if we might reach it. So reading this book has certainly been educational and a good way for me to reflect on my own experiences over most of that period, but it becomes also very clear how much more there is to do, and will always be. And with this I wish you a nice Saturday evening and hope you will take some time for active recovery so we can work towards this vision, and probably new and updated visions soon, together!

P.S.: Edit 30 seconds after posting this blog post. Fun fact. I spent literally HOURS fiddling with the image below as a compilation of what I was reading and all the cool figures in the book. And then, when the text was ready to post, I chose some nice featured image from a walk this morning and forgot that I had just created the image below. Anyway, I think the main benefit of creating it was for me to think through it and it is actually a horrible figure, but now at least I have it included here, too…

Hine, D. (2023). At work in the ruins: finding our place in the time of science, climate change, pandemics and all the other emergencies. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Macintyre, T., Tilbury, D., & Wals, A. (2024). Education and Learning for Sustainable Futures: 50 Years of Learning for Environment and Change. Routledge Focus