Thinking about neuropsychiatric disabilities and inclusive teaching after a seminar today

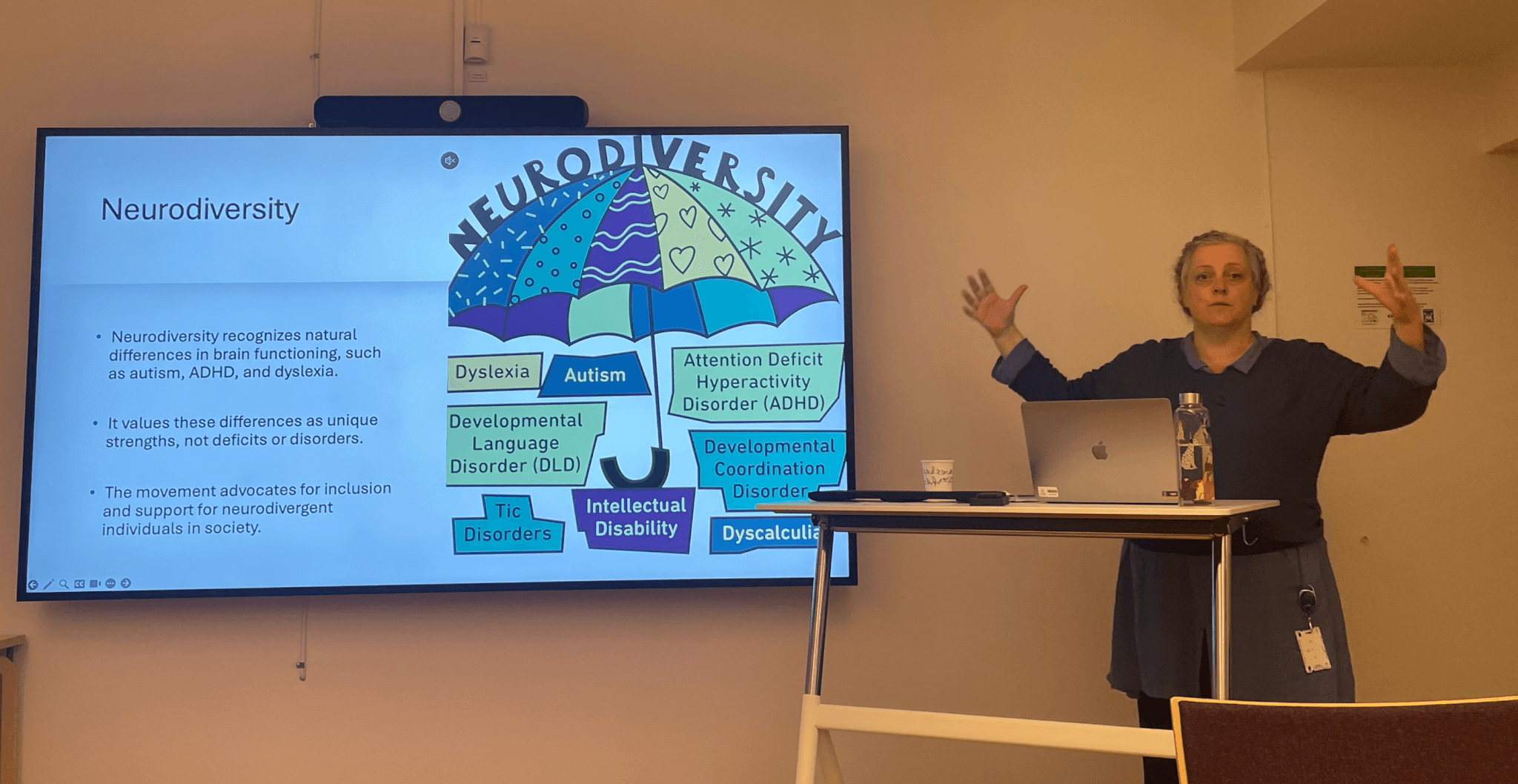

In today’s third meeting of the “Inclusive Lund University” course, Linda Stjernholm talked about “neuropsychiatric disabilities and inclusive teaching”.

She started out with my favourite “office analogy” to explain the three main brain functions (see in more detail in the post below).

An office as an analogy to explain the three brain functions

In a nutshell, the three main brain function is somehow getting information in, represented in the analogy by a doorman (or, as one participant suggested, doorkeeper, which I prefer because it is gender neutral). The doorkeeper can let a lot of information in (like mine -- for example the whistling thermos in the meeting room drove me crazy to the point that I had to go there and open the lid and stop the sound), or it can be very selective and filter what comes in. Depending on the topic whether it is interesting or not, or depending on how information is presented -- in text, visually, as audio, experiential, or depending on lots of other factors.

Once information has entered the brain, it is processed in an office. The office can be highly structured or chaotic, have good systems to hold relevant information ready to use or not, can have internal conflicts, or any number of other setups. And as teachers, we can support optimal processing here by for example providing structure.

How doorkeeper and office play together is regulated by the manager, who can put systems in place to optimise efficiency or energy consumption, and minimise mistakes. My manager, for example, likes checklists. My manager also recognises that my doorkeeper is letting in way too much information, so in order to keep the office working, sometimes the doorkeeper needs to reject all new information. I typically have a day or so every month where I do not want to meet or talk with anyone, that's when my office needs to do an inventory of what is going on, my manager needs to work on the processes and readjust. Since I recognised that my brain needs that time, I have become much better at planning it in before my brain demands it through going into a migraine... And here we can also support students by helping them recognize what their manager needs to do to keep everybody else playing together nicely.

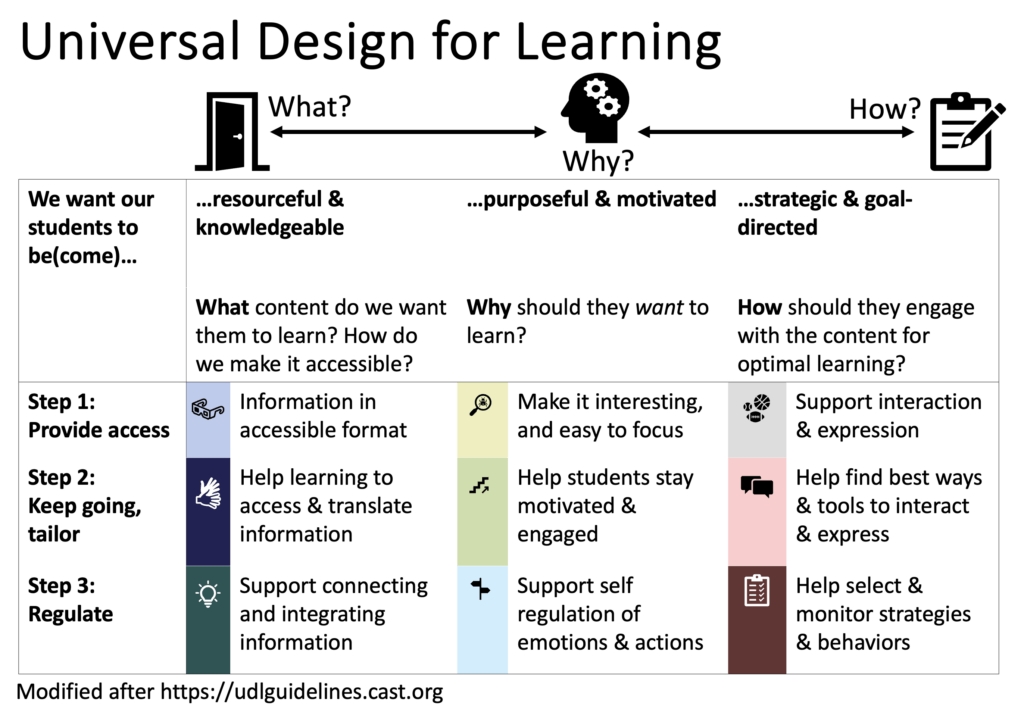

To me, the office analogy works beautifully together with the Universal Design for Learning framework (if we switch the first two columns...).

Regulating energy is an important topic when dealing with neuro-divergent students. Here, Linda presented the "spoon theory". The spoon theory explains that we have limited energy (we only get a certain number of spoons full) and have to focus on what is important (allocate the spoons accordingly). Not everybody starts out with same number of spoons, and we don't use the same number of spoons on the same task.

One example Linda gave was using public transport to work -- for some, that takes a lot of energy, for others, it does not. That made me think about how I like being at work at 7 in the morning. Not because I couldn't think of something fun to do at home before I go to work, but because I like avoiding the main mass of commuters, and especially the teenagers driving to school, that I would meet if I went to the office at 9 or 10 like my colleagues. I like coming on the bus, saying good morning to the driver, sitting down in a row that I have all to myself without having to search for one, not hearing anything except the driving sounds and maybe a faint bit of the driver's radio, and during the winter even sitting in the dark until I arrive in Lund. I had never really reflected on why I do it this way, but when she mentioned this example I realised that I am regulating what I spend energy on. As few spoons as possible for social interactions or any other kind of input on the bus! And a start in the office where I do not need to put energy into social interactions until I have already gotten some work done.

Next, we talked about autism, dyslexia, and ADHD, and our experiences with students with those diagnoses. In my small group, we talked about how we had noticed (as anecdotal evidence) that people with dyslexia are often willing to correct "guesses", both for what word comes after a line break when they have extrapolated and it turns out that the author wrote something else, but also in conversations, where my experience at least with one specific person is that they are always open to reconsidering and correcting assumptions and prejudices, in a way that I think is really admirable. And my interpretation is that this is because of the repeated experience of having misread or mis-interpolated, and a humbleness that comes from that. Whereas other people (like me) might double down on what they first thought and be not as willing to consider that they might be wrong. But of course there might also be cultural and personality factors involved in this, and it is also something that I should maybe work on. Anyway, moving on...

Later on in that conversation, I said it's sometimes easier to deal with untypical student behaviour when we know they have a diagnose. Another participant in my group re-phrased it as us being more forgiving when we have a label. And this is actually quite scary -- why do we need a label to be compassionate?

Then, we moved on to find some "pain points" and to discussing what we can do about them. Here, the advice to use the "plus one" thinking is very helpful. Don't try to optimise everything at once, do one small step at a time!

I shared that I always include a sentence in the welcome email to a new course along the lines of "I want us all to have a good experience in this course. What can I do to make it easier for you to engage and participate?". My experience with that is that participants then let me know about things that are really easy to fix for me but make a big difference for them, like that they hear more on one ear than the other, so they need to sit in a specific position relative to where sounds are coming from. So much better to have asked and then fixed a potential problem than not!

We also discussed that it is sometimes difficult when we ask students about how many breaks they want. Typically, nobody responds to that question, probably because nobody wants to impose their opinion on the whole group. So what could we do? I would in general advise to rather have more short breaks than one long, but in any case, we could for example use a menti to ask anonymously and get responses from most of the students. Or we could ask them to all close their eyes and raise their hand at the option they prefer. And, as one participant advised, don't ask about whether someone wants a break, just DO a break. If you are thinking about it, there is very likely someone who will benefit from having one!

But speaking about how to have these conversations with students, how can we facilitate conversations among students about how we work together in a good way? We obviously don't want to "force" people to disclose information that they do not want to disclose (and in any case, that is both a problem when it comes to GDPR and to Lund University policy regarding harassment, so really don't do it!), but in a large group, we could for example use a menti to ask about who has felt that they have certain preferences, or who has "a friend" with a diagnosis, or show the numbers that Håkan showed in this course's first meeting that make it very likely that in any student group there are people who have certain disabilities.

Also, it is good to be aware generally how perceptions of situations are really subjective. For example, in one of the last courses I taught, one of the participants confided in me a couple of sessions after we had done an introduction round that the time waiting for their turn to present themselves looked like a massive workout on their fitbit because they were so stressed and their heart rate went through the roof. I also don't like waiting for my turn in such rounds, and I typically don't listen very well because I am preparing what I am about to say, but I had no idea some people were affected this badly! Of course there is a benefit of asking everybody to speak very early on in a course so they have heard their own voice in the room and don't build up a huge threshold to speak, but at what costs? There are great alternative methods, for example the Liberating Structure "impromptu networking".

Other things we talked about are providing advanced organisers, basically outlines of the session or the course, not just in the ppt presentation, but on a flipchart on the wall next to it, to always provide orientation about where we are at in the plan. Or to have headlines in the header of a presentation that also let us know where we are and what is about to come.

We also touched on "hands-on tactile assignments" and what they could be in courses that don't have a design/creative/building component. For example, we could have a competition in creating the coolest cover for a report, or a video? Lots of ways for students to get in touch with their artsy and creative side that don't necessarily have to be official learning outcomes but could just be additional offers and engage students in a different way with the content. This reminds me of how I tried to model wave phenomena in a sand box a while ago, and how that was at the same time super difficult and super cool.

But from this we moved on to speaking about competitions, and how they are very motivating for some, but extremely off-putting for others. I have had the experience that participants completely disengaged and refused to even physically being close to where a (what I thought) very playful and low-threshold competition was going on. But how could we make sure that those students are still engaged in the learning, even if they don't want to engage in the competition itself? We could, for example, consider creating roles for them, like being a judge in the competiton, or a journalist documenting. It might be good to ask for volunteers for those roles not as "is there anyone who does not want to compete", but rather "who would like to document the process?". That way, people who really do not want to compete get an easy way out, and if the roles are designed well, they still need to engage with the content just as deeply as everybody else.

Unfortunately, at this point we were really out of time and had to leave. But luckily we'll have the next meeting in two weeks!

Project presentations in the "Inclusive Classroom" course today - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] and how they play out in different ways in different people, neurotypical or not? There is the office analogy, of course, but also the spoon theory, where spoons represent units of energy that someone has […]