Thinking about assessing sustainability competencies

Current goal: Figuring out how to do assessment of sustainability competencies for a pass/fail course (where the fail option is an actual option*).

Usually we recommend starting from the learning outcomes so we know what to actually assess. Right now we don’t have those yet, and I cannot set them by myself. We also wouldn’t think about assessment completely independent of learning activities. But I am preparing possible assessment tools to have available when we are discussing the learning outcomes and activities, so I have an overview over what options we have available from the literature.

A great place to start from is the overview over what assessment tools for sustainability competencies are currently used, in Redman et al. (2021). I wrote about that article before, and below is a summary figure. In a nutshell, there are three types of assessment tools that are used: the ones where students express their own perception, the ones where teachers (or external stakeholders) observe student performance, and the ones where we assess texts that students write. There is an overlap between the types; course work can be text based, for example, or we can observe how students argue when explaining their concept maps.

I really like the icons in ppt, sorry… But they help me remember more than just the words on the picture alone!

So far, so good, this gives us ideas of what we can do and what seems to work. But searching for more literature, I did not find much there that goes beyond that, neither giving substantially different tools, nor in terms of how to use those tools well. Most authors only mention methods, but not in so much detail that I understand what exactly they did.

One distinction that I find helpful when thinking about assessment is whether we want to measure or judge a student performance (And I really recommend you read Hagen & Butler (1996) on this!!).

Traditionally, and especially in STEM, we like to believe that we can do scientific measurements of student learning. One example of someone doing that on sustainability competencies is Waltner et al. (2019), who develop “an instrument for measuring student sustainability competencies”. Measuring knowledge alone is difficult enough (do we assign the exact weight to knowledge about the climate system as knowledge about society? Or which one is how much more important? And what are the pieces of knowledge that we need to check so they represent “knowledge of the climate system”?), but when it gets to competencies, this really falls into the trap of social desirability. Even though Waltner et al. (2019) mention that as a problem in the discussion, at least for the sample items given in the article, it is obvious what the desired response is (type “when I hear of cars that consume a lot of fuel, I get angry.”). And it might be more obvious to older kids than younger, and maybe girls on average react to social desirability more than boys, and just like that, we can explain the results of the study just by social desirability (my interpretation, not the authors’). So a scientific measurement approach to assessment might sound nice in theory, but in practice it really does not work that way.

But then a judgement approach, where we rely on experts knowing whether someone is performing a task to an acceptable standard or not, are highly subjective. In order to help students to know what experts will think about their performance, and also to help evaluators be on more or less the same level with what they judge is acceptable and what not, it is helpful to use rubrics. There are a couple of rubrics that I found in the literature that can be helpful to consider.

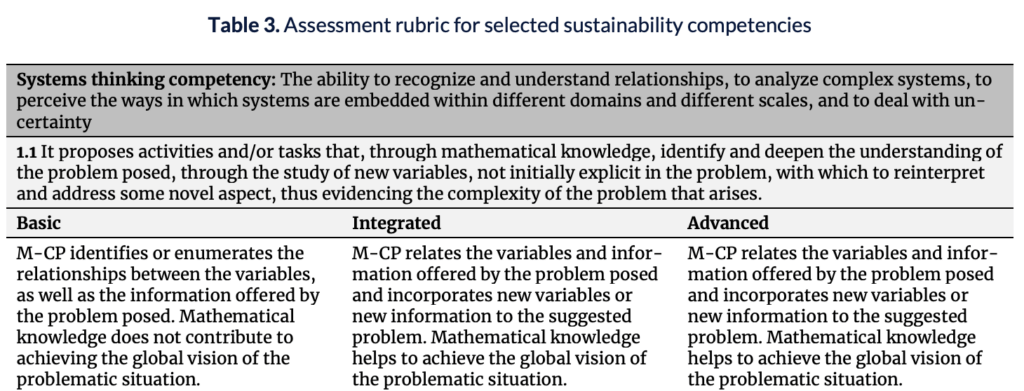

García Alonso et al. (2023) present a rubric that they used to assess sustainability competencies in project proposals that future maths teachers wrote. Below is an example entry from their Table 3, which gives their assessment rubric for selected sustainability competencies.

In their table, they start out with describing the competency they want to assess, and then operationalising it. They then give descriptions of three levels: Basic, integrated, and advanced. This can be really helpful (even though, looking back at the operationalised competencies in Wiek et al. (2015), having each competency operationalised through only one to two sentences each seems very simplified).

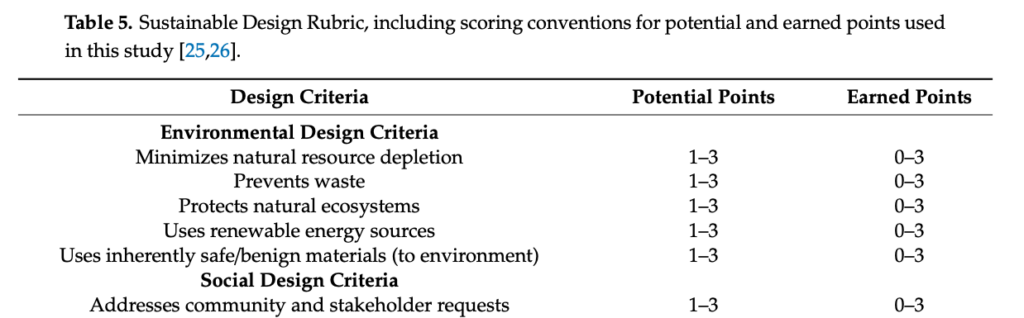

Another example is Watson et al. (2020), where they use “nine principles of sustainable engineering” which they expand into criteria (see the first few rows of their Table 5 below). Watson et al. (2020) acknowledge that not every project has the chance to address each criterion in the same way just because not everything is equally relevant to all projects, and therefore scale the weight of each criterion through “potential points”, i.e. 1 point for “yep, somehow relevant” to 3 points for “critical”, and then give students 0 to 3 points, depending on how well they match expectations.

I think this is a very interesting approach! It acknowledges the local context, in which those criteria are perceived as more relevant than UN goals or other frameworks, and the very specific context of each project, where maybe some criteria should carry a much larger weight than others.

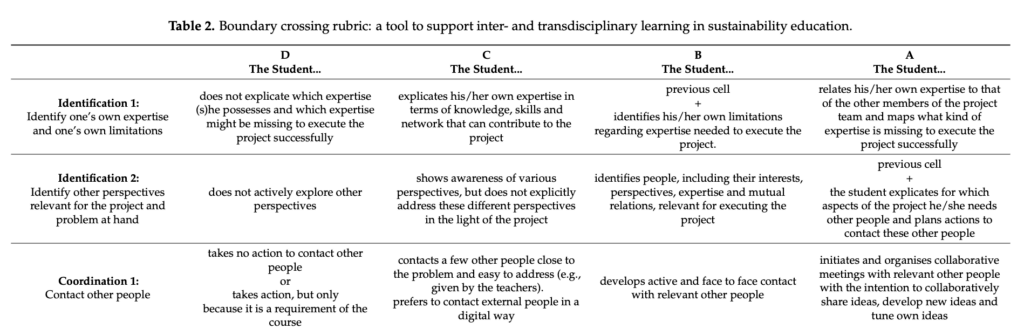

Another really interesting example is the one by Gulikers & Oonk (2019), who develop a “rubric for stimulating and evaluating sustainable learning”. They use the framework of “boundary crossing”, figuring out how to understand people from different contexts, with different values and different ways of expressing themselves, to make transdisciplinary learning visible (which is super difficult as we see in all the examples above). In boundary crossing, there are four learning mechanisms:

- identification is about understanding the core identities of oneself and others. Questions to ask oneself to stimulate this learning mechanism are for example about what expertise I have and lack, or how other stakeholders relate to each other

- coordination is communication with the other. Questions here are for example about approaching and communicating with other stakeholders

- reflection is about identifying and taking on perspectives. Questions are for example about how to understand others perspectives

- transformation is creating knowledge by bringing elements from across the boundaries together. Questions are for example about how to get and make others excited about a new practice

From that, Gulikers & Oonk (2019) develop criteria that describe “the successful boundary crosser”, and a rubric that describes what meeting the criteria at different levels would look like (see the first couple of rows of their Table 2 below).

I find this rubric very helpful and actually inspiring. In the article they describe that it helped teachers both describe learning outcomes more explicitly but then also assess student learning, but that it is also a good tool to coach students, for self-assessment, and for reflection, and I can totally see this and want to explore this further.

Even though I started this post writing that I want to figure out how to pass or fail students in a course, using an instrument like the one by Gulikers & Oonk (2019) can be great not only for the summative, but also the formative, the assessment for learning (Wiliam, 2011). And we can build assessments the way suggested by Forsyth (2023); over a longer period of time where students for example first pick a topic and get feedback on that, then write an outline, get feedback, do the literature review, get feedback, etc, and maybe including some of those parts into the summative assessment, collecting points towards the eventual “pass”, rather than having one big, scary, standalone exam in the end. Especially for sustainability competencies, it is probably also a good idea to think closely about authenticity of tasks (see for example Ashford-Rowe et al., 2014; Ajjawi et al., 2024).

Do I know now how to assess sustainability competencies? No. But I definitely have a good idea where to start to figure it out for our concrete case!

*Why do we want to fail people on sustainability competencies? We obviously don’t want to fail people. We want to make sure all graduates have reached some level of proficiency, so we need to define what that level looks like, and make sure that people reach it. The best outcome is of course that everybody ends up reaching it, but if they haven’t reached it yet, we want them to spend a little bit more time and effort on it until they do.

García Alonso, I., Sosa Martín, D., & Trujillo González, R. (2023). Assessing sustainability competencies present in class proposals developed by prospective mathematics tearchers. Avances de investigación en educación matemática.

Gulikers, J., & Oonk, C. (2019). Towards a rubric for stimulating and evaluating sustainable learning. Sustainability, 11(4), 969.

Redman, A., Wiek, A., & Barth, M. (2021). Current practice of assessing students’ sustainability competencies – a review of tools. Sustainability Science, vol. 16, pp. 117-135.

Waltner, E. M., Rieß, W., & Mischo, C. (2019). Development and validation of an instrument for measuring student sustainability competencies. Sustainability, 11(6), 1717.

Watson, M. K., Barrella, E., Wall, T., Noyes, C., & Rodgers, M. (2020). Comparing measures of student sustainable design skills using a project-level rubric and surveys. Sustainability, 12(18), 7308.

Wiek, A., Bernstein, M. J., Foley, R. W., Cohen, M., Forrest, N., Kuzdas, C., … & Keeler, L. W. (2015). Operationalising competencies in higher education for sustainable development. In Routledge handbook of higher education for sustainable development (pp. 241-260). Routledge.

Attempting to Assess Key Competencies in Sustainability - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] we need to combine the assessment tool with some form of assessment criteria. I recently wrote a longer blog post on the topic where I show different rubrics from the literature (and I found it rea…, but what I think is most important to consider is what indicators can we observe that someone has […]