Guest post by Kirsty Dunnett: “Thinking about my positionality as a teacher and researcher in physics education and academic development”

I thought a lot, and wrote (e.g. here), about my positionality in relation to my work recently, inspired by conversations with, and nudging by, Kirsty. Below, I am posting her response to my blog post, where she shares her reflections on her own positionality and also on why and how we need to be careful with demanding, or expecting, or even just implying that we think people should be, sharing that kind of information. Definitely worth a read, thank you so much for sharing, Kirsty!

Enter Kirsty:

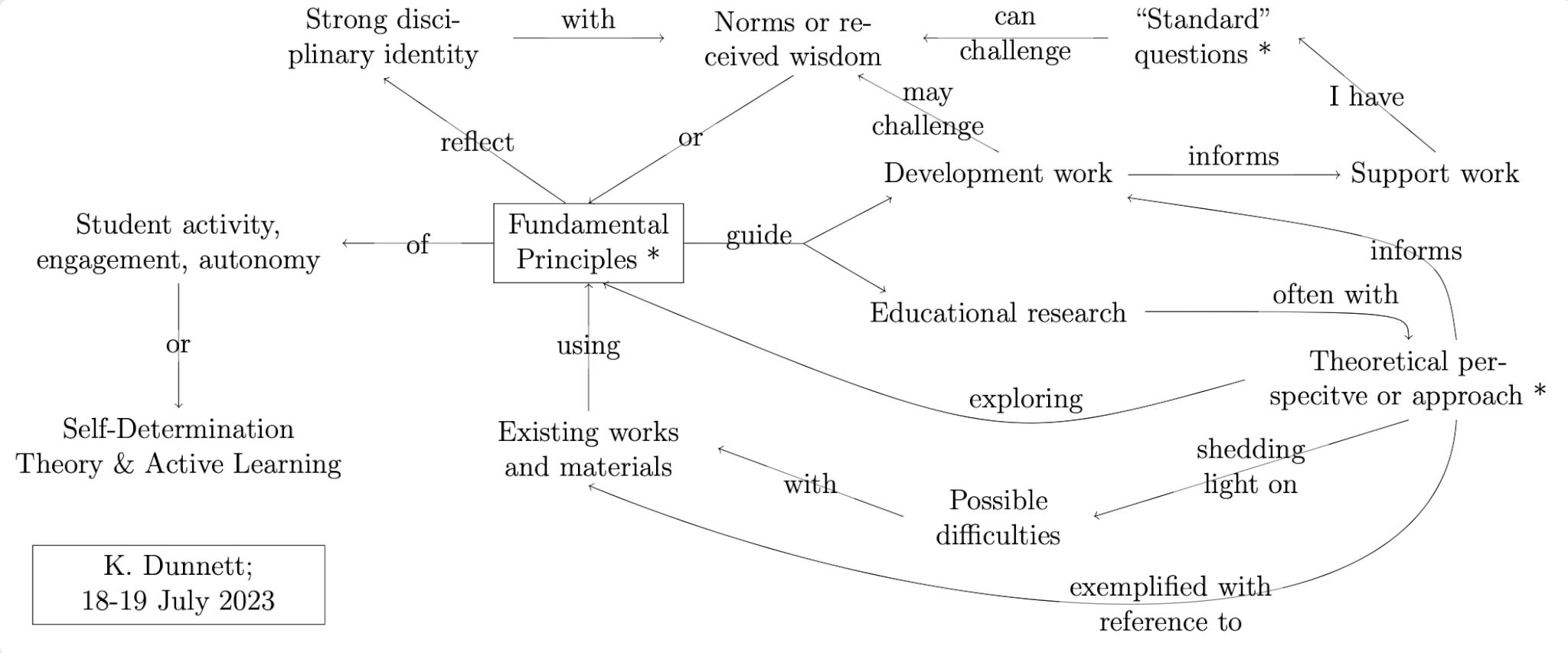

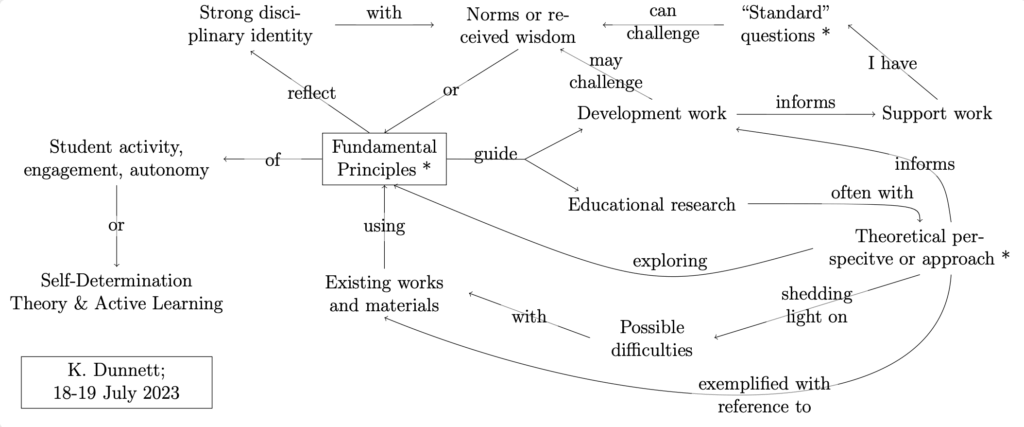

The ‘task’ Mirjam referred to in her blog on this topic was one I’d done for myself after reading Kinchen et al.’s 2018 article. Having come across the article, and being a fan of concept mapping, I decided to do the concept mapping exercise for myself, and found it both illuminating and somewhat discomforting activity (see figure for what I came up with). I knew that I was going to be looking for reflections of my background in theoretical physics in my ways of thinking and working in an a very different area. In mapping what I think of as recurrent or central aspects of my practice, I could see not only how my tendency towards theory manifests, but also how deeply my thinking has been influenced by the norms of academic physics. This is not only the disciplinary practices, but also the culture and the dominant discourse or rhetoric, especially that surrounding teaching (or education) and inclusivity.

How I understood my disciplinary background in (theoretical) physics as being reflected in my work with academic development and education research in July 2023. A lot of what I advocate can be summarised in a very few basic points, that, to use physics jargon, reflect some ‘fundamental principles’ (active learning, student autonomy). These lead me to ask a fairly ‘standard’ set of ‘what if’ questions (e.g. ‘what if you have a university without any undergraduate students?’), that reflect the way physics asks ‘what if this is sent to zero or infinity’. However, both the value I place on education, and the approaches (active learning, inquiry practical work) are contrary to the ‘traditional’ teaching practices of physics. In my educational research work, I often develop a very theoretically driven perspective or approach – particularly, for understanding things and possibilities. However, having been trained as a theoretical physicist, I’m happy to use previous works to exemplify my work, rather than collecting my own data to illustrate this understanding. I do also use theory as is more more typical for educational research, as a means of framing the work, but this isn’t in the figure, and from my physics background, I am aware of how starting with a theoretical framing can blinker my thinking, so there’s a whole other discussion there.

In preparing to discuss this with Mirjam a few of weeks ago now, I realised that this exercise was a means of articulating my positionality within my educational research and development work, so I wondered whether there had been any efforts to concept map positionality in education research. This led me to the second paper in Mirjam’s blog that considers specifically social identity and is framed in the context of critical studies work in which it is particularly important to understand and acknowledge the researcher’s identity (or identities) in relation to the research work.

This time, one might say Mirjam set me the task to sit down and do the social identity mapping. I took the full list of social identity factors proposed by Jacobson & Mustafa (2019), and answered each item I could to tier 1 (basic answer) and tier 2 (main influences). And this is where this apparently straightforward activity put discipline-based mapping into context. Because by focussing on a discipline, I had been able to focus almost exclusively on my professional training and the context in which I might work; personal questions did not need to be put on the table. But Jacobson & Mustafa’s social identity map is based on ‘demographic’ data, and essentially reflects what others see or classify me as. The tier 1 answers were mostly straightforward, and even the tier 2 answers largely unproblematic to answer.

However, recognising the first exercise as a means of articulating positionality and thereafter finding the second article is the result of encountering a demand for positionality statements – or at least information, and I suspect that this demand is going to become increasingly standard in the type of work I am hoping to spend a fair amount of time doing and publishing. But, though I agree with Mirjam that explicitly understanding our own positionality is a good thing, in doing the second exercise, I found that the (accurate to me) answers to a whole number of points are things that I consider as nobody’s business but my own, and are not things I believe, or believe anyone should believe, are directly relevant to my professional competence.

Most of the boxes are likely to be easy to answer for most people, a good number (i.e. all the ones about gender, sexuality, etc.) include information that is classified as sensitive personal information and fairly strictly protected under GDPR: this, if nothing else, indicates that there should never be any expectation or request that this information is shared publicly in any form, and this includes in research articles or as part of courses in which participants reflect on their positionality.

This raises questions about what parts of a social identity map should be declared – in whatever context. Which all goes back to a rather different fundamental principle: no one deserves to be pointed at with the (implied) statement ‘oh, look, someone different‘; nor should anyone feel obliged to point that out about themselves. This also applies to seemingly innocuous questions that implicitly cover aspects of Jacobson & Mustafa’s social identity map, especially if they are likely to include an emotional reaction. One example is ‘where is home?’ when there might be an immigrant status involved – I’ve experienced this, incidentally when I, a Brit, was visiting a group in the UK, it’s deeply uncomfortable (as is being a visitor amongst strangers and the only person not drinking alcohol).

‘Don’t need to share if you don’t want to’ is not good enough since it still imposes an expectation of sharing. For some with non-majority identities this is likely to add stress to the exercise: if one is not practised at not answering such questions, one might share information one later would rather one hadn’t; otherwise, one might force oneself to share things that fall under anti-discrimination laws; the alternative is to labelled ‘churlish’ or ‘not a team player’ by (correctly) refusing. In countries where it’s usually safe to admit to certain differences, one might simply not wish to introduce oneself as such to strangers; for citizens of other countries, a public documentation could eventually lead to death by official means.

From my experience to date with positionality statements in relation to research articles, the increased emphasis on positionality is seeming to tend towards a demand for non-specific additional information that does not materially contribute to the work. Journal editors and reviewers have a particular responsibility ensure that only information that is directly relevant to the research is included or requested in a research paper (yes, this may mean telling researchers that they have provided irrelevant information!). Moreover, increased articulation of positionality in research articles should not set a norm where ‘being out’ is compulsory for everyone: doing this exercise and understanding what others may think reasonable to demand of me in the future has not helped me think I might have the academic career I want. A study should surely be of interest to the academic community because the knowledge it contributes, not because of the personal factors of the authors, and valued because of its quality. To request or make public ‘demographic’ information about any individual involved (in whatever role) unless the work explicitly makes use of these aspects seems to run counter to the whole idea of inclusivity. In particular, this can put researchers, especially early career researchers who are vulnerable both professionally and to others’ demands, in situations that are, at best, uncomfortable or lead to a misrepresentation of themselves; it also sets in stone an identity that may later be revised.

As far as I can understand my work, my disciplinary background is the dominating influence on the work I do and the conclusions I reach, and I suspect that this may be so for many academics. Articulating one’s social identity, for example, though the framework developed by Jacobson & Mustafa, can hardly harm, so long as it is left as a private exercise. A professional discussion should usually be structured around professional topics – in this instance professional identity. Depending on personal experiences, aspects of social identity will appear in a professional, discipline focussed map: these are clearly the ones that are relevant.

And what of my thinking about concept mapping? When jotting down my answers in the linear structures proposed by Jacobson & Mustafa, I had already identified some of the connections between the different aspects. However, to turn this into a concept map where these different aspects interact, proved even more challenging than anticipated, and I quickly abandoned the attempt. What I could do, though, was separate the items into two distinct groups: socio-economic (class, immigrant status, employment status etc.), and what I’ll call ‘personal identity’ (gender, sexual orientation etc.) aspects. And I could then review my answers, particularly my tier 2 elaborations, and consider whether I felt the facet had had a positive, negative or neutral aspect on my (professional) experience. In this way, I could, articulate for myself, in the roughest terms, the way in which my social identity affects me as a researcher and academic developer.

Reading up on the purpose, pros and cons of positionality statements - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] started from us drawing up our own positionality statements and discussing the differences [see hers and mine — and I would do mine substantially different now after a lot of thinking has gone […]