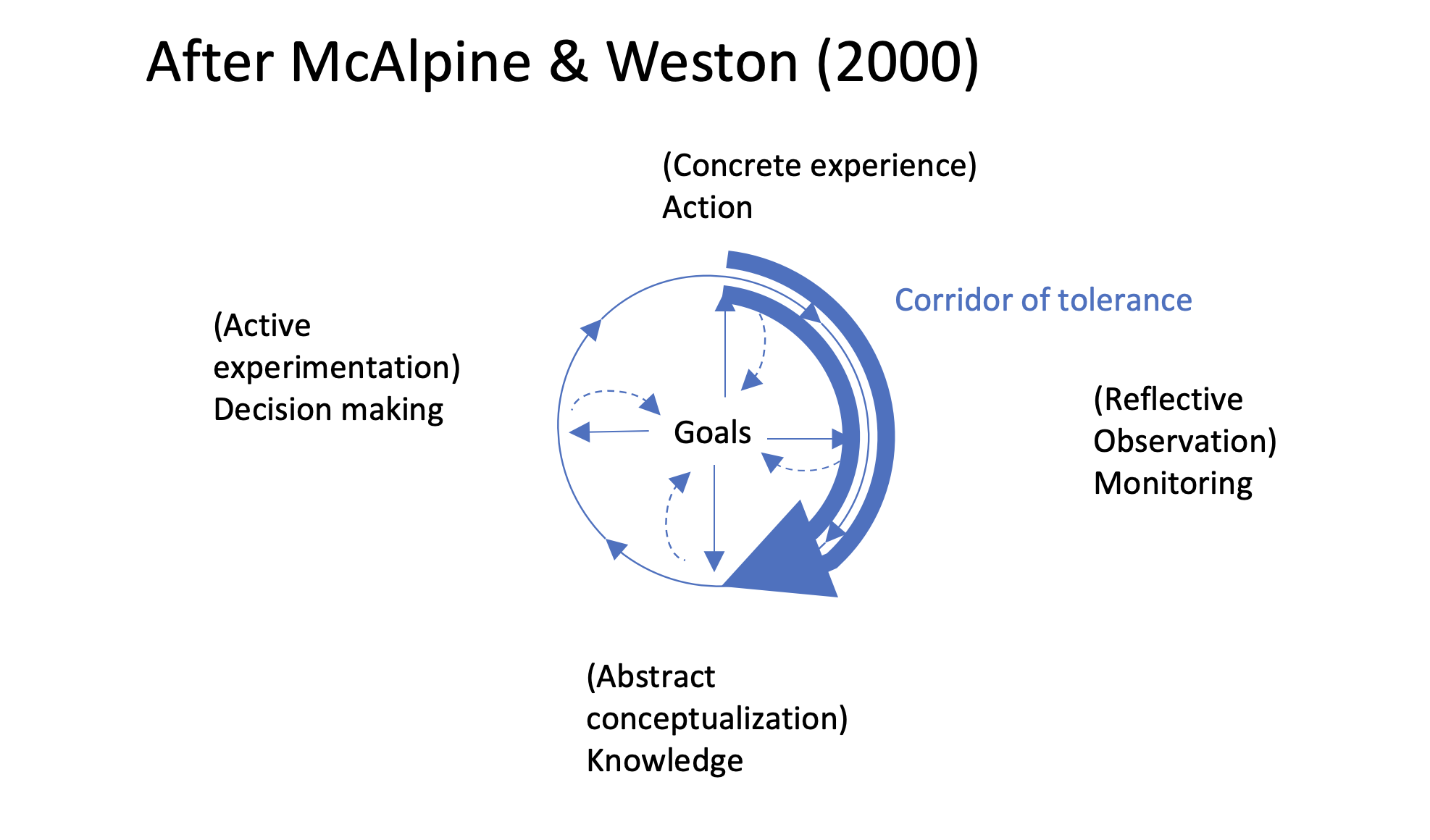

Kolb (1984), Olsson & Roxå (2013), and McAlpine & Weston (2000): Learning cycles and how closely do you stick to your planned teaching?

Experiential learning cycles are everywhere in my work in academic development, so here is a brief overview over how they are used to describe and support teachers developing their teaching.

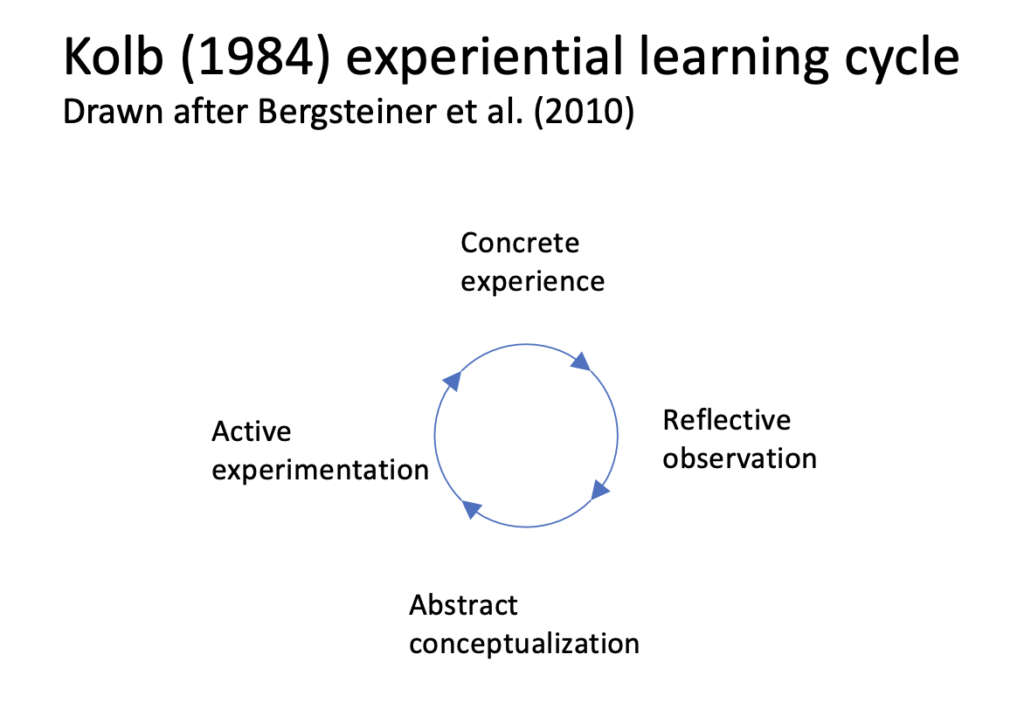

It all starts from the Kolb (1984) book and the “experiential learning cycle”. I have only ever read a few pages around where the model is presented, and I am not a huge fan, but the model itself has been widely used and accepted. I am redrawing it here following the suggestion of Bergsteiner et al. (2010), because they fixed a bug with the graphical syntax that has been bugging me ever since I first saw the original model, so I don’t want to reproduce it here.

But the idea in the model (whether presented graphically correct or not) is simple: There is some kind of concrete experience, for example in the classroom for a teacher, that serves as basis for reflective observation. The observations are made sense of with some form of theory input, reading of literature, or some other abstract conceptualization. Based on all this, the active experimentation part starts, where the next concrete experience is planned, and the cycle starts over. This model works no matter where the cycle is entered (in higher education we would usually start from theory before planning experiments and reflecting on them), and the phases can have different lengths and weights depending on context, but it is important that all four of them happen. So far, so good. This model works for student learning or for teacher learning.

Focussing on teachers, Olsson and colleagues developed the “LTH pedagogical competence model”, which consists of actions in all the four phases. The “action” phase is the actual teaching a teacher does, and the student learning that results from it. But being efficient in the classroom alone is not enough to be pedagogically competent according to this model. The teaching needs to be followed up with observations that make sense of what happened in the classroom — why did students misunderstand something, or behave in a certain way, or did they think what I thought they would? These considerations should be informed by reading literature on teaching and learning, and by “informed pedagogical discussions” with peers. Out of this phase, the teacher comes into a planning phase for the next teaching, which is then informed by all that has happened so far, and its where the cycle starts over again.

This is the basis for much of our work — creating spaces for teachers to learn from each other through sharing observations and helping each other interpret; making sure that arguments are based on literature and not gut feeling.

In parallel developments, a similar cycle has been used by many others. McAlpine et al. (1999) describe how, when teaching, teachers monitor student behavior for reactions that might help the teachers understand how engaged students are, if there are difficulties with the material or in group interactions, etc.. Teachers also monitor themselves. And both can be trained to become faster and include more different clues, which helps with reflection in action (so during teaching, in contrast to reflection on action, that happens afterwards). Depending on the cues that the teacher gets, they have to decide on whether they want to adapt their teaching, or stick to their initial plan — both in terms of methods etc, but even whether they want to change the goals they had. Teachers typically use verbal (“the question gave me an opening”) and nonverbal (“they were fidgety”) cues from the students, as well as written work (“good quality”) and assessments of student states (“they jumped right into it”). McAlpine and colleagues coin the term of a “corridor of tolerance” (see featured image at the top of this post), which is the width of the space to the sides of what was planned that a teacher is comfortable staying in, before taking actions to bring the class back to what was originally planned.

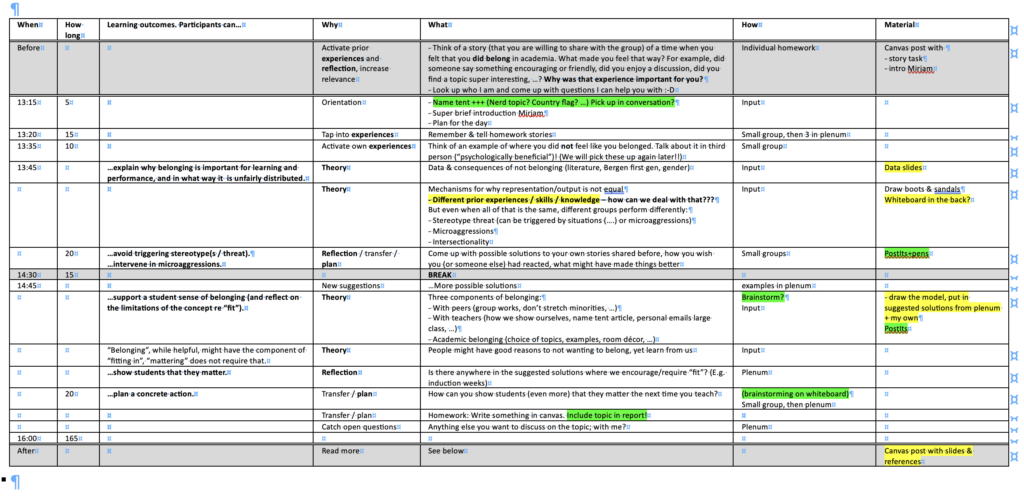

I find this concept of a “corridor of tolerance” quite useful when reflecting on teaching. I tend to have a very detailed plan (often down to 5 minute units of what I want to happen — see image below for an example of a course planning that I did, and screenshot during the development process, and put in a presentation about planning…), but then I also tend to completely not stick to it and change both short-term plans and even goals during the course of a lesson. Having a very detailed plan helps me keep in mind what my goals originally were, so I can make quick decisions about whether I want to stick to them, drop one or several, or go completely off script. Especially knowing how much time I had estimated for later phases is very helpful when deciding to spend more time on something, because it makes it easy to figure out where that time can come from. All the other columns are useful, too, not just my notes on what the main points are, but also which phase in the experiential learning cycle I am in (e.g., am I skipping all opportunities for planning and only focussing on reflection?) and what kind of activity is planned (e.g., do I get rid of all opportunities for group work to make time for discussions in the plenum?). I’m digressing, but this was to make the point that thinking about learning cycles can actually be quite useful!

P.S.: Bonus image: My corridor of tolerance here is very limited — if I move to far to either side, the reflection of the star will move out of the porthole. And we can’t have that!

Bergsteiner, H., Avery, G. C., & Neumann, R. (2010). Kolb’s experiential learning model: critique from a modelling perspective. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(1), 29-46.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning. New Jersey, Eaglewood Cliffs.

McAlpine, L., Weston, C., Beauchamp, C., Wiseman, C., & Beauchamp, J. (1999). Monitoring student cues: Tracking student behaviour in order to improve instruction in higher education. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 29(2/3), 113-144.

Olsson, T., Mårtensson, K., and Roxå, T. (2010). “Pedagogical competence: A development perspective from Lund University”. In Ryegård, Å., Apelgren, K., and Olsson, T., (Eds.), A Swedish perspective on pedagogical competence. Uppsala University, Division for Development of Teaching and Learning.

Olsson, T., & Roxå, T. (2013). Assessing and rewarding excellent academic teachers for the benefit of an organization. European Journal of Higher Education, 3(1), 40-61.

More thoughts on teaching consultations menus - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] to somehow capture how what I offer fits in the general process of improving teaching is to use the Lund pedagogical competence model by Olsson et al. (2010) and map my different offers on it. This is a quick and dirty mock-up. […]

Slow reading of "Becoming an Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School" by Venet (2024) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] we use Kolb’s experiential learning cycle to talk with teachers about student’s and their own learning, and Hamshire et al. (2024) also recommend approaching wicked problems in higher education with a […]

Currently reading: "Teachers interacting with students: an important (and potentially overlooked) domain for academic development during times of impact" (Roxå & Marquis, 2019) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] researchers. And, of course, their perception of what is happening in the moment: teachers have a corridor of tolerance (McAlpine et al., 1999), within which they are willing to deviate from their planned teaching in […]