Currently reading: “A conceptual framework for the teaching and learning of generic graduate attributes” (Barrie, 2007)

When my colleague sent this article to a student we are collaborating with the other day, I decided that it was about time that I read it, too. Last time I looked at it, it seemed quite inaccessible, so I put it on the “for when I have time” pile. But reading it this time round, I actually started seeing that the framework presented in Barrie (2007) is actually really useful for teachers and academic developers. So here is my summary (including my visualizations of my understanding, because I still find their presentation quite hard to follow).

The backstory to this article is that many universities have started advertising generic outcomes that all their graduates will achieve (probably things like problem solving and being a team player), but when you actually try to figure out where students are actually being taught these skills, it is not necessarily obvious, and teachers and administrators might have different conceptions of what it is that students are supposed to learn, where and how it happens, and whose responsibility it is that it does.

In his study, Barrie (2007) brings order into the chaos and develops a framework to talk about “generic graduate attributes” and where they are taught and learned.

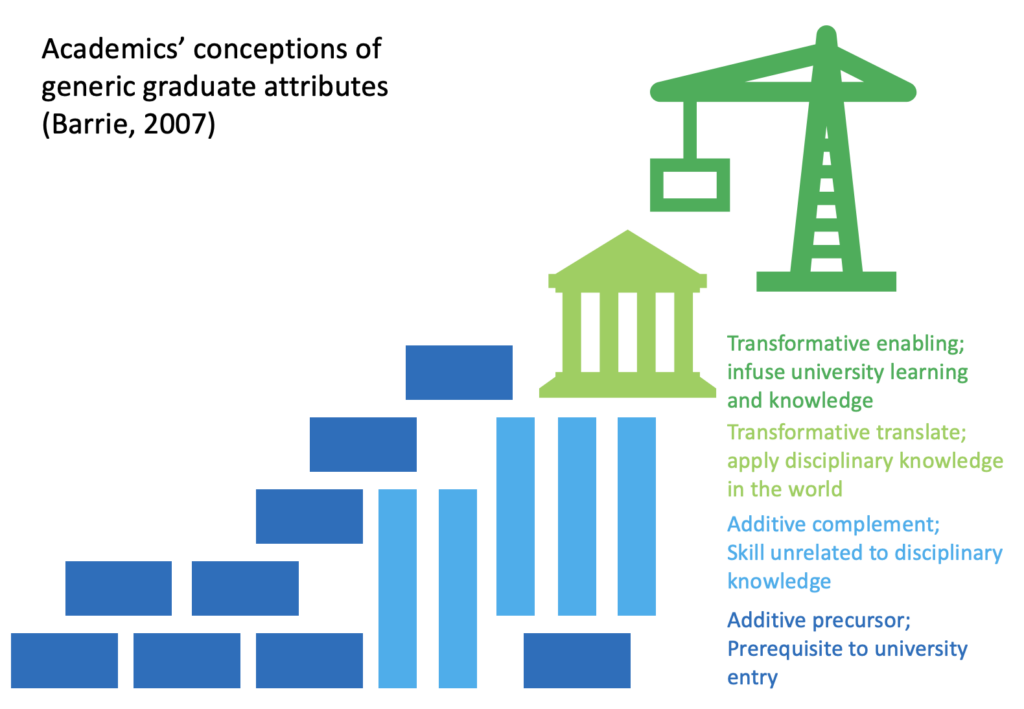

He describes four distinct ways people think about generic graduate attributes (see my interpretation below):

- The lowest level of understanding is called “precursor conceptions”: the generic skills should have been acquired before entering university and are distinct and additive.

- The next level is “complement conception”; here skills are learned at the university in addition, supporting — complementing — the disciplinary learning that is taking place.

- The third level is “translation conception”, where the generic graduate attributes are about translating disciplinary university learning into the real world and new contexts, thus transforming rather than adding.

- The highest level is “enabling conception”, which is again about transformation of learning, knowledge, and the student themselves.

Even though in my picture above it looks like those conceptions are building on each other, that’s not the case; they are held by different people!

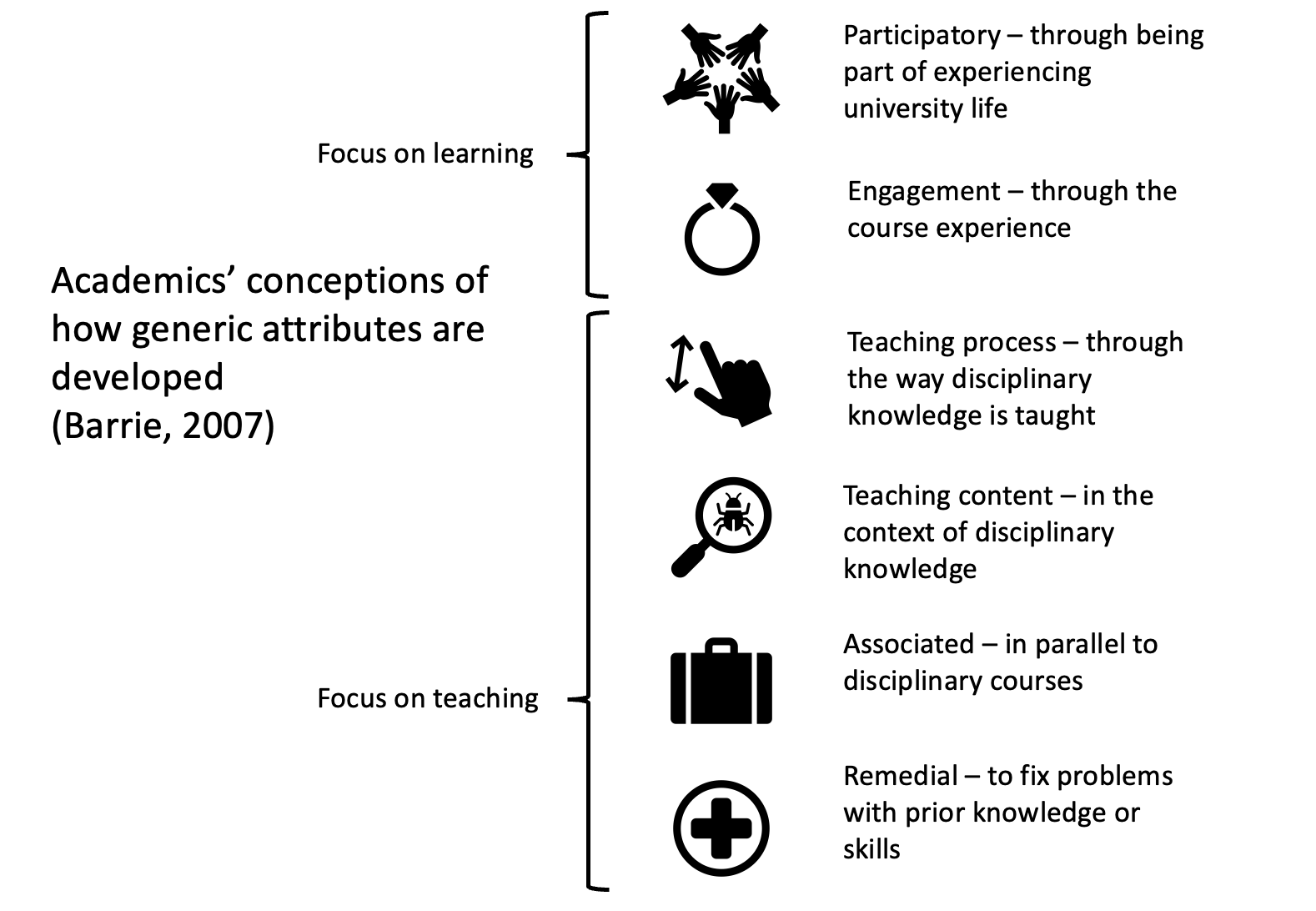

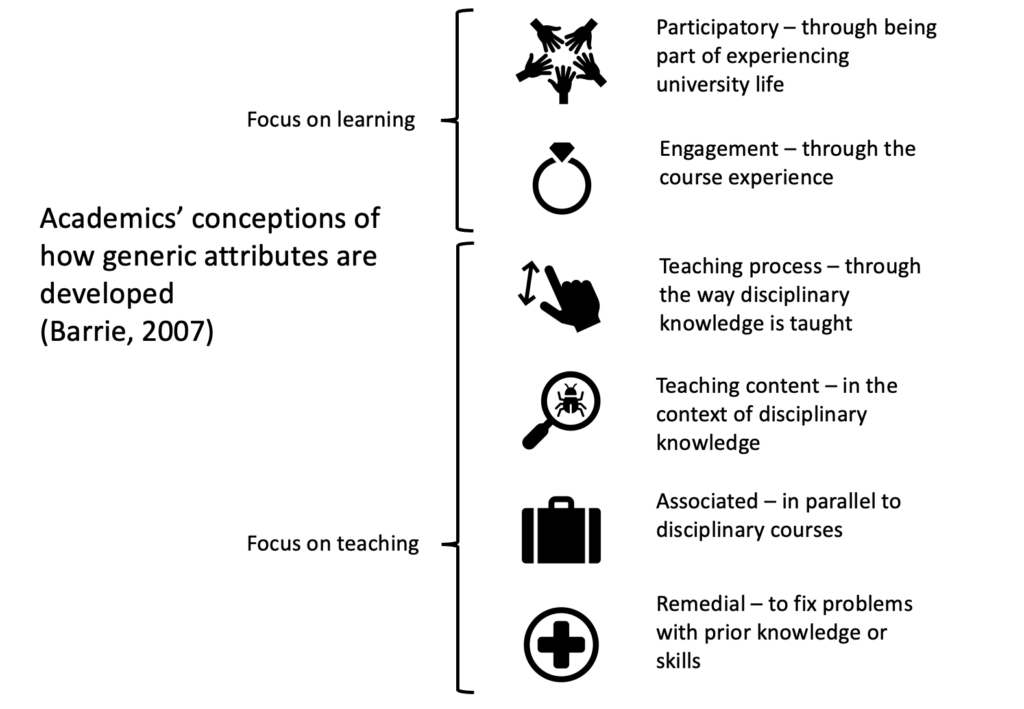

Anyway, he then looks at what academics think how students should acquire all those generic graduate attributes, and there are six different ideas about that:

- The first idea is that this shouldn’t be part of university education at all; students should come already equipped with those skills. So if the skills were taught at university, that would only happen “remedial” in a “putting out fires” kinda way, to fix a problem with students’ prior knowledge. What comes to mind here are the kind of math pre-university trainings that were offered when I was a student: two weeks before the official first week to get up to speed on what university expects.

- The next idea is “associated” — the teaching should happen at university and for all students, but in supplementary teaching units to the disciplinary ones. This is quite common, I think — having for example writing or programming sessions that are not connected to any disciplinary content, even though they might happen inside a disciplinary course. (But more often, they are probably separate courses?)

- The next idea is that the generic attributes are part of the “teaching content”, i.e. taught together with disciplinary knowledge. So this would be a programming course that uses disciplinary examples, ideally related to what is happening in other courses at the same time; or even teaching of programming integrated in disciplinary courses; or a session on writing a lab protocol in the lab course itself.

- Then, generic graduate attributes can be taught through the “teaching process”, i.e. not making them an explicit topic but rather designing the teaching in such a way that through learning the disciplinary content, students also learn the other skills.

- In the next idea, it is about where and how things are learned (rather than taught), and here it is through “engagement” with course learning experiences. Except for the change in focus, this is fairly similar to the previous idea.

- In the last idea, it is again about learning rather than teaching, and generic graduate attributes are learned by “participating” in “all the experiences of university life”, engagement with the intellectual and social community inside and outside, in a formal and informal way, not just one or two (ot three, you get my point) courses.

Looking at all these different understandings of what generic graduate attributes are and where & how they should be taught, it is maybe not surprising that it is really difficult to find consensus. And in that sense, having this framework is a really useful tool to elicit other people’s conceptions in order to make sure we are even talking about the same thing, or understand where we disagree!

(Barrie then goes on to look at whether the “what” and “how” are related within individuals, and not surprisingly, generally, the higher the level in one, the higher the level in the other. But at that point I lost interest ;-))

[Edit: Mirjam might have lost interest, but Kirsty did not. Read her summary of the rest of the article here!]

Barrie, S. C. (2007). A conceptual framework for the teaching and learning of generic graduate attributes. Studies in higher education, 32(4), 439-458.

Kirsty says:

Thank you! I should probably read the original… I wonder in science how much the generic skills, even when they’re part of the teaching content, process or either of the learning approaches, get lumped onto particular (probably practical) courses because that’s where they ‘fit’, and it means the knowledge transfer idea(l) of theoretical courses doesn’t need to be questioned.