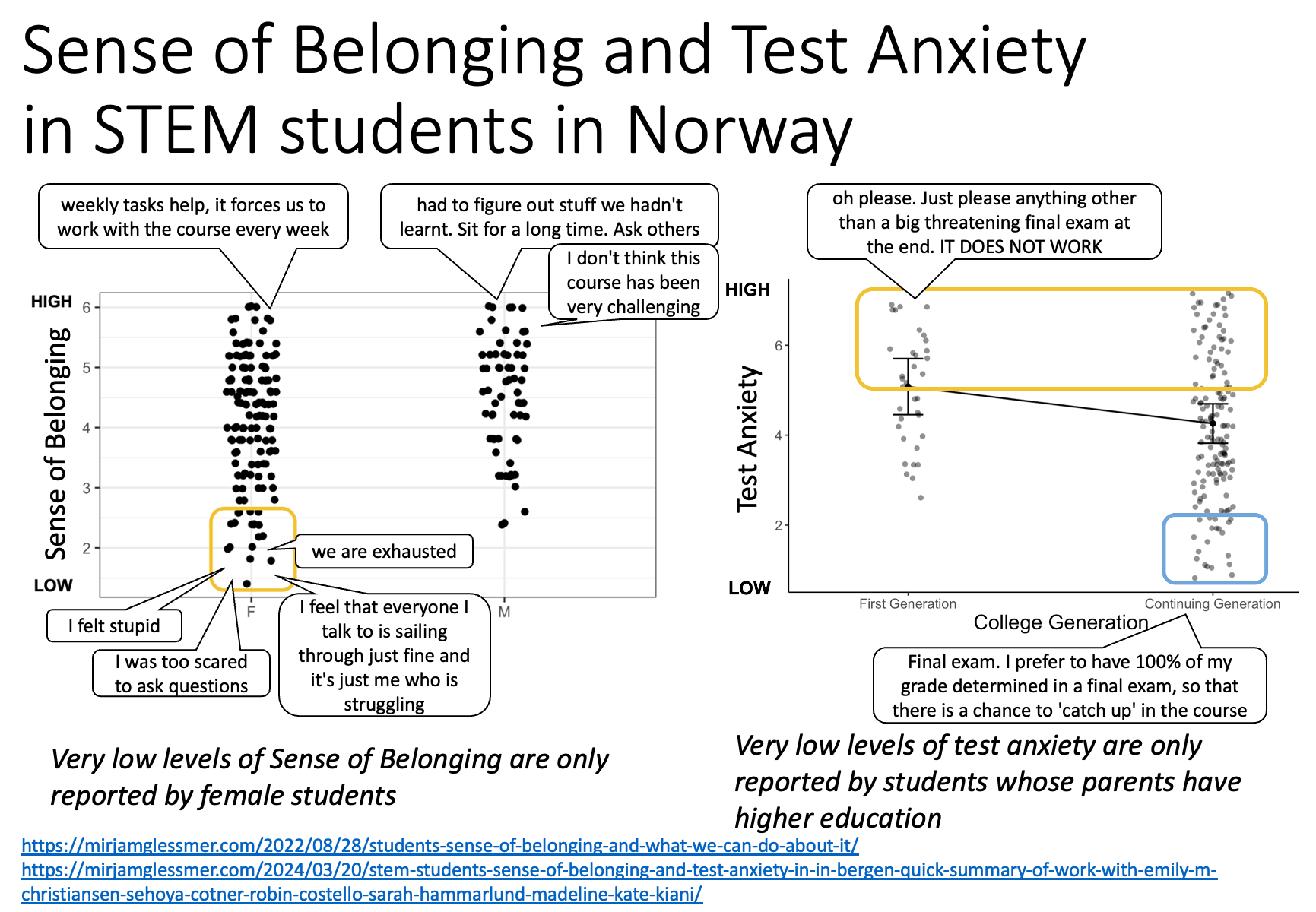

STEM students’ sense of belonging and test anxiety in in Bergen (quick summary of work with Emily M. Christiansen, Sehoya Cotner, Robin Costello, Sarah Hammarlund, & Madeline Kate Kiani)

In my series of things-I-want-to-say-in-an-upcoming-workshop-but-suspect-I-might-skip-to-make-time-for-participants’-topics, here is a quick summary of work I did with Emily M. Christiansen, Sehoya Cotner, Robin Costello, Sarah Hammarlund, & Madeline Kate Kiani on STEM students’ sense of belonging in Bergen a while back. The results are very interesting, mostly because they are very similar to what we have read […]