Currently reading Curzon-Hobson (2002) on “A Pedagogy of Trust in Higher Learning”

Trust is often perceived as risky — what if students cheat, what if they don’t put in the effort we want them to put in, what if they don’t learn what we want them to learn — and therefore, there are dozens of rules in place that very much restrict students’ freedom and guide them on their way. But, as Curzon-Hobson (2002) argues, students need to experience freedom to figure out “how to live and learn in a meaningful way“. And — what I find the most interesting point — the same holds true for teachers to some extent!

But let’s take one step back. Curzon-Hobson (2002) states that the goal is to create “unique potentiality“, “student’s willingness to continually become what they already are not”. This means approaching learning, and life in general, from the perspective that “one must choose, and hence question, think and act anew“, and be willing to take a step back from what seems known and safe, a step outside of the frameworks one is operating in, and be willing to take the risk that comes with the questioning, thinking, and acting anew.

Trust, in this context, means more than trusting that the teacher is an expert and fair in their assessment of students’ work, it means trusting the teacher to care and to challenge to the extent that students become willing to take risks to show themselves as learners, as becoming who they can be.

To make this kind of trust possible, teachers need to “reveal how knowledge is subject to human interpretation and praxis, and that there exist conflicting perspectives across cultures and epochs that are constituted through continuous and changing interrelationships“, and with this, show themselves as human and imperfect. “The teacher is seen in the eyes of the students as a learner who also feels confusion, doubt and excitement“, as someone who also “needs this particular learning environment to further realise and test out his or her understanding“. “This breaks down the perception of the teacher as an unquestionable expert and the underpinning power relations of this dynamic. It is a relationship instead that accentuates the perception of the teacher and his or knowledge as also becoming, incomplete and unfinished. The aim is to reveal that he or she is still learning, has made errors, will continue to do so, and strives to become what he or she is not already“.

How can teachers set the conditions for this kind of trust to be formed in them? Curzon-Hobson (2002) has several suggestions:

- dialogue in the classroom where the teacher also takes notes and asks questions and thus signals that there is something happening here that isn’t just the “same old, same old”, but worth remembering and coming back to later

- inviting students to co-create their learning; the questions they work on, their assessment, their grades

- being open about limits of expertise and own struggles, and being willing to learn from students

- sharing how their own understanding and ideas have changed over time, and how current ones are questioned by peers

- inviting students as colleagues into the research process, where the teacher is more likely to show up naturally as a learner, and can learn together with the students

Students also need to “trust the teacher to provide the critical foundations for the fragmentation and re-imagination of their perceptions of their interrelationships“. For this, teachers need to be aware of the students’ experiences and contexts, understand what is revolutionary in their frame of reference.

But the teacher is still in a position of power. While students need to be willing to accept the teacher’s authority, the teacher must be willing and able to not abuse it, but rather create a challenging and demanding learning environment: “direct the learning experience so that students will encounter those things that change their perspectives of their interrelationships, see things anew and yet also be brought back from those things that hinder this development“.

But of course, trust between a teacher and a group of students is not only influenced by what happens between them and cannot be controlled by the teacher, but is embedded in everybody’s prior experiences and the bigger context, and while trust between teachers and students is necessary for learning, it is not sufficient. Other forms of trust can impact the kind of trust described above:

- The community might trust the teacher to do a brilliant job while at the same time setting constraints on time, space, money, etc that make it impossible to live up to that trust

- Nationally or institutionally prescribed frameworks of learning outcomes that the teachers have to work within might not align with the promise of innovation that the university makes

- “Teachers might also be trusted by the institution to fulfill the grandest of mission statements, yet work in the full knowledge that these are simply marketing devices which cannot be attained in an environment characterised by competition and individualism” (ouch, that one hits home!)

- Industry might trust teachers to “fairly” assess learning, ignoring the limits in the assessment systems and the consequences that has on non-typical students

- Teachers might be trusted to use certain types of materials, knowing full well that they are not optimal (Curzon-Hobson (2002) mentions computers and textbooks, somehow my mind went to learning management systems…)

- The institution might trust the teacher to promise employability and status that the teacher knows the education cannot promise

- Institutions might trust the government which might be deceiving them for their own purposes

If trust is understood as policy, it limits what teachers can do: what learning outcomes, what forms of assessment, what content, what methods they can use. But “trust is not something that can be stimulated or realised through prescriptive policy, but rather developed through a freedom that generates teacher’s energy and imagination“. Prescriptive policies — whether to students or teachers — feel like being mistrusted, and “the sense of trust experienced by students in the classroom may be radically altered as teachers themselves lose control over and responsibility for the conception and execution of their teaching time”

I find this bigger perspective so interesting (after, of course, nodding along with everything about trust between teacher and students, all fits nicely with our own work), not just that of course everybody’s prior experiences and current circumstances influence trust in the classroom, but also how there are so many bigger picture constraints trickle down and influence trust in the classroom. In a system so full of distrust and policies that are designed to replace the exact trusting learning relationship described above for fear that it can be abused, how can teachers and students break free and still trust, still “question, think and act anew“?

Curzon-Hobson, Aidan (2002) A Pedagogy of Trust in Higher Learning, Teaching in Higher Education, 7:3, 265-276, DOI: 10.1080/13562510220144770

And after these depressing thoughts, here are some recent wave-watching pics for some joy and grounding. First, my favourite picknick bench.

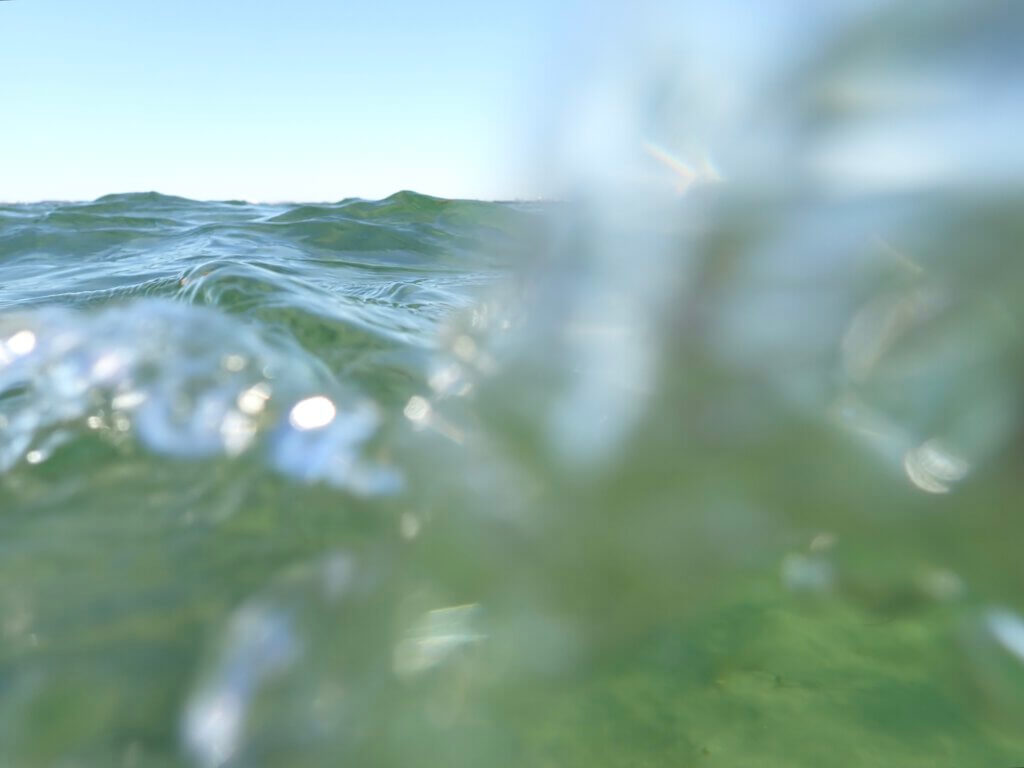

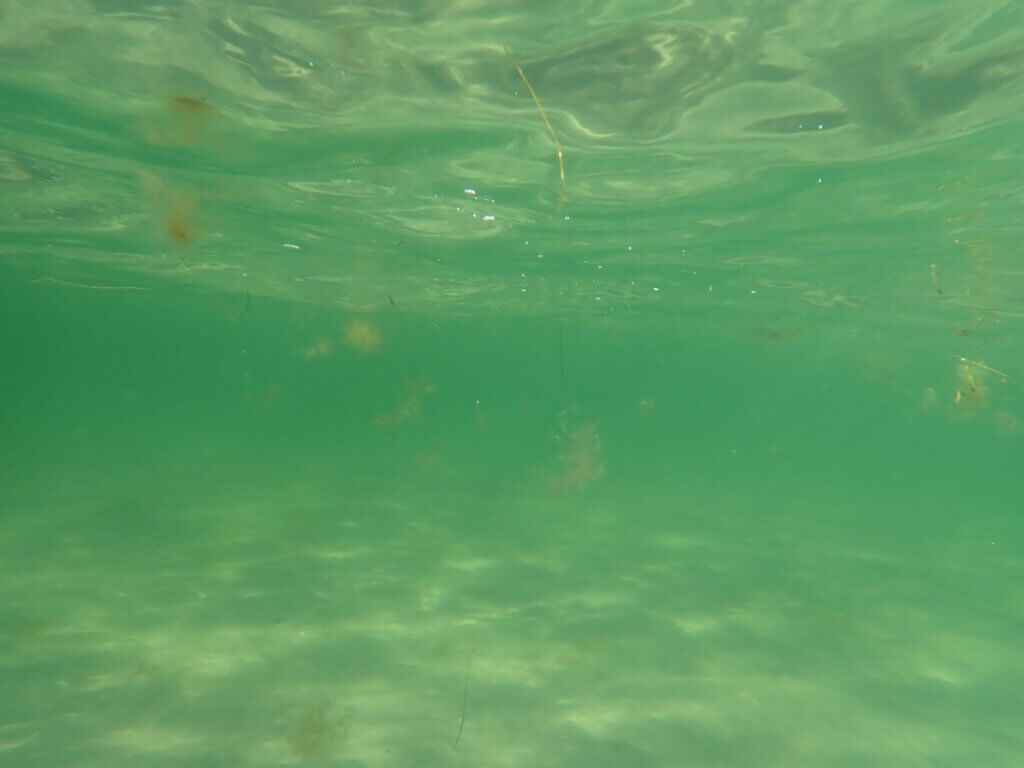

And then swimming with the waves!

Lots of capillary waves on top of the larger ones. Always fascinating!

So many scales all at once!

And here: a bit of horizon and a bit of wave crest!

Floating in the waves…

And looking at a wave from below the surface!

Sometimes this happens, too. But isn’t it cool how you get the undisturbed view of the surface in the top left, and then the look right into the water, at the sandy seafloor, in the bottom right?

I love waves!

Even though there seems to be a lot of stuff floating around in the water!

A glimpse of Malmö and the Turning Torso…

All gone again!