The political dimension of teaching for sustainability (currently reading Håkansson et al., 2018)

A very common remark when talking about Teaching for Sustainability is that it is political and we shouldn’t indoctrinate our students, hence stay away from politics, and thus from sustainability teaching. My take on that is that everything is political since politics is about how we want to live together in society, but that there is no(t necessarily) indoctrination in discussing. But luckily there is literature on this…

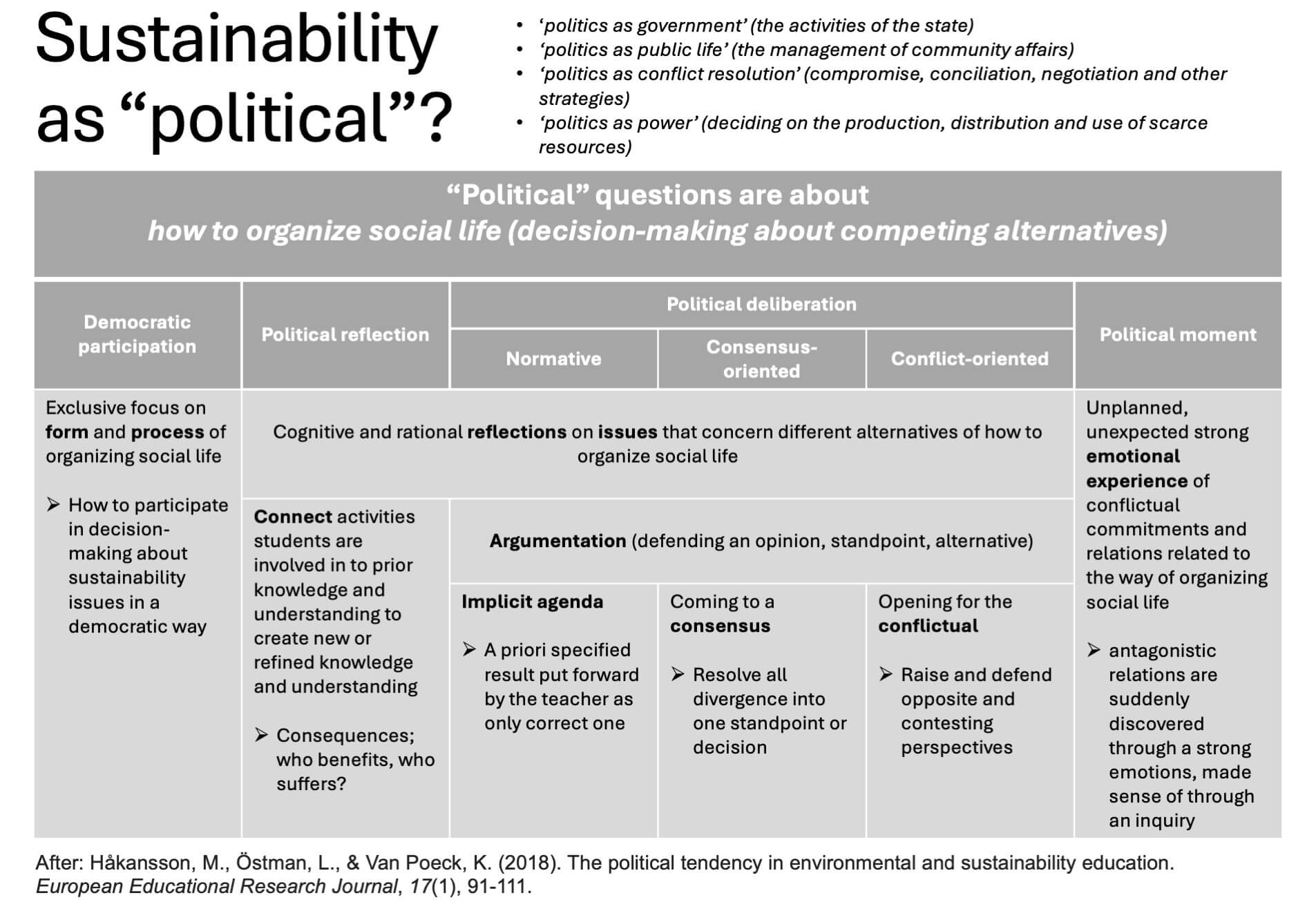

Håkansson et al. (2018) look at different ways in which politics can come up in (sustainability) teaching. They look at situations that address “how to organise social life recognising that this inevitably requires decision-making about different and competing alternatives“, including “‘politics as government’ (the activities of the state); ‘politics as public life’ (the management of community affairs); ‘politics as conflict resolution’ (compromise, conciliation, negotiation and other strategies); and ‘politics as power’ (deciding on the production, distribution and use of scarce resources)“. From those examples, they construct a framework / typology (“the political tendency”). I have redrawn their table (see above) because that always helps me to understand better.

In a nutshell, situations that somehow address how to organise social life can fall into one of four categories:

- Democratic participation, where the exclusive focus is on form and process of organising social life. The learning outcome here is how to participate in decision-making about sustainability issues in a democratic way, independent of any concrete sustainability question.

- Political reflection, which is a cognitive and rational reflection on issues that concern different alternatives of how to organise social life, and which connects activities students are involved in to prior knowledge and understanding, to create new or refined knowledge and understanding. So this is about discussing consequences (who benefits, who suffers?), but without taking a stand.

- Political deliberation, which is also a cognitive and rational reflection on issues that concern different alternatives of how to organise social life, but now it is about argumentation (defending an opinion, standpoint, alternative). There are three sub-categories:

- Normative deliberation, which has an implicit agenda, meaning an a priori specified result put forward by the teacher as only correct one (so this is where I can see the problem with indoctrinating students)

- Consensus-oriented deliberation, which is about coming to a consensus and resolving all divergence into one standpoint or decision

- Conflict-oriented deliberation, which is opening for the conflictual and the point is to raise and defend opposite and contesting perspectives

- Political moment, which is an unplanned, unexpected strong emotional experience of conflictual commitments and relations related to the way of organising social life. Antagonistic relations are suddenly discovered through a strong emotions, made sense of through an inquiry.

Looking at Biesta’s purposes of education, we can link this to qualification/preparation (for the next level course, a specific career, taking care of a family, or, in this case, democratic participation), socialisation (values and norms to participate in society — democracy, but also normative deliberation to come to “the correct”, socially accepted conclusion, or even consensus-oriented deliberation if consensus is a value in society), and lastly person formation (being and becoming a person — both within existing societies (“identification”) and discovering new ways of doing and being (“subjectification”)). For person formation, we need the freedom and challenge of forming and expressing own experiences (conflict-oriented deliberation) and also the emotional experiences of antagonism (political moments).

Håkansson et al. (2018) stress that there are always “companion meanings”: In addition to the explicit learning outcomes on for example STEM content, there is also always implicit learning that comes with it about who the student is, where they fit in, where they want to belong, so it is possible to not teach about politics in some way.

I had read this article a year or two ago already, but this time round it made a lot more sense to me. And in a year or two, I might fully understand it…

Håkansson, M., Östman, L., & Van Poeck, K. (2018). The political tendency in environmental and sustainability education. European Educational Research Journal, 17(1), 91-111.