Quick summary on reading about how to write a role play for learning

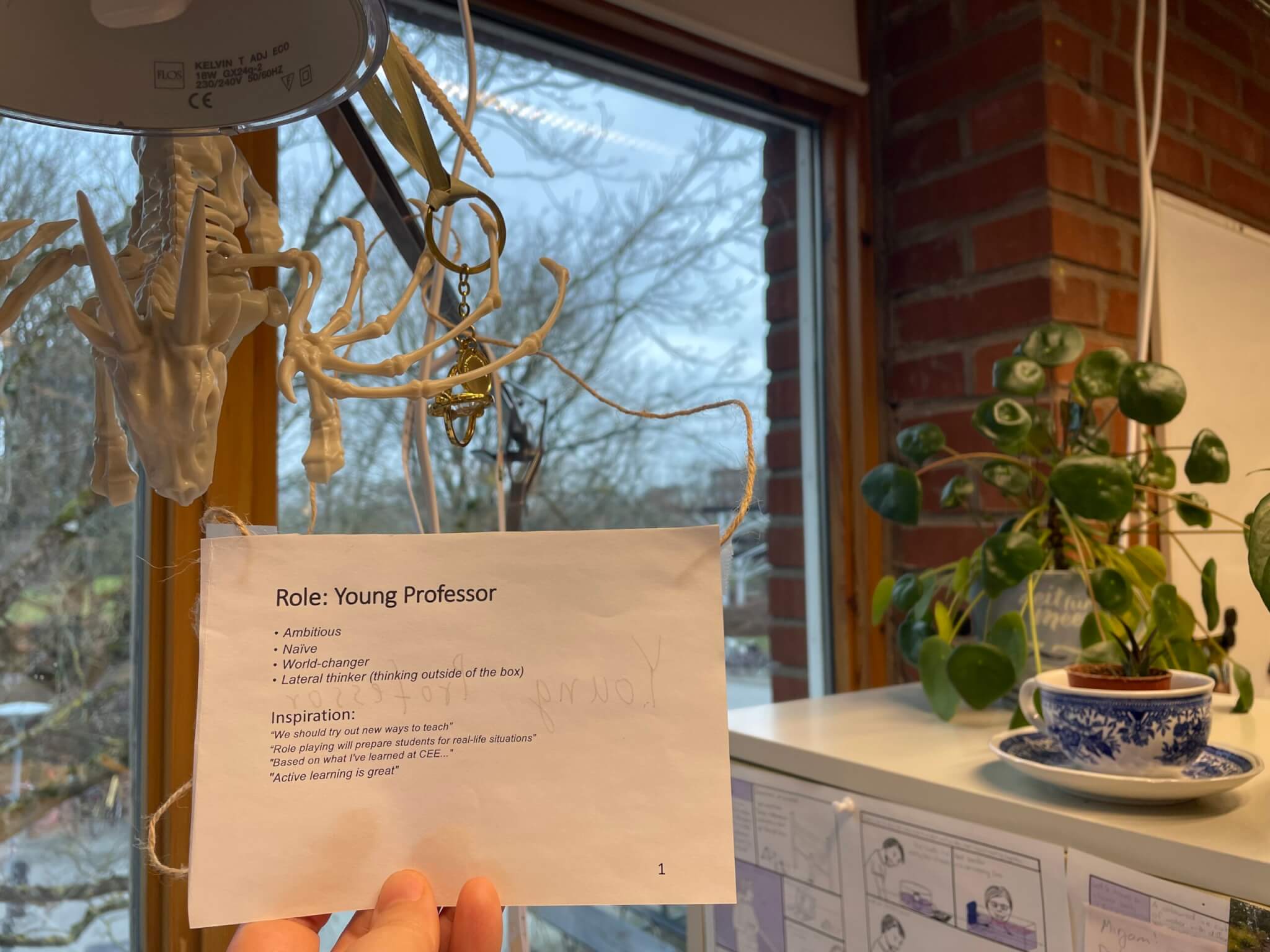

One way to help students engage with what they value and believe themselves, and how values and beliefs and interests influence what positions people take, might be setting up a role play, where students take on roles that they might find themselves in in the future. I do not have a lot of experiences with role plays myself (and I also tend to hate having to “play” in that kind of settings), but I totally see the value in doing it (even if that means that I have to play myself). Role plays are used in many different ways (almost as elaborate simulations on the complicated and preparation-intensive end) and for many different purposes. The featured image of this post is a role description from a role play that participants in my Introduction to Teaching and Learning course set up a while back when they did microteaching — so they only had 10 minutes to run the role play (including people reading about their role and what it stands for) with the purpose of teaching the other participants about role plays as a teaching method. They choose to give people a tag with the name of their role on one side, and then a super quick description and talking points on the other (which I thought was a great idea, hence it has been hanging on my desk lamp ever since). The example that inspired my reading for this post is a role play that Thomas Hickmann has developed on world views, to help students articulate their values and practice values-thinking, which he writes about here.

But so what makes a good role play in teaching?

In “Death of the role-play” (what an intriguing title!), Alexander & LeBaron (2009) suggest that role plays are often too far removed from reality so that they aren’t actually engaging, because they take place in this artificial teaching setting and within traditional hierarchical relationshios in teaching. Instead, they suggest using other forms of experiential learning, like adventure learning: for example, negotiating what and how to prepare for dinner has very real consequences that can easily include hangry and grumpy participants, so the negotiation situation has a lot more relevance than negotiating some fictitious situation that nobody cares about. They recommend moving torwards creativity, challenging participants to reveal themselves authentically, create and use the opportuntities for self-discovery and reflection, more meaning through focus on own experiences and associations. Their focus is on learning negotiation techniques, but if we take those thoughts with us, what can that mean for our context?

Writing the role play

Really important idea first, also suggested by Alexander & LeBaron (2009): Instead of just writing a role play yourself, co-write it with students, or let them write role plays for each other to play! They can bring in the topics they think are most relevant, they can do the background research, etc.. Of course in negotiation with you, or based on rubrics that you provide, depending on how much co-creation or student independence you feel comfortable with. Westrup & Planander (2013) describe sharing a script that isn’t complete and giving students time (in their case 45 minutes) to add to the script before the role play starts.

Lönngren (2021) suggests that wicked problems can be used as basis for role plays (students prepare individually by either reading some assigned reading or doing their own research, and then prepare to take different roles in small groups). They develop 8 design principles for good problem descriptions:

- Use a problem that you think will engage your students (and as mentioned above — student can give input on that!)

- When you design the roles students are to take in the discussion, make sure that the roles have sufficiently different perspectives on the issue to lead to interesting discussions (at the same time, Alexander & LeBaron (2009) recommend to avoid making the situation too dramatic and sparkly and obviously fake, it should be a realistic composite of real cases)

- Provide enough background information so that students are actually able to discuss the issue (also a recommendation in the “teaching sensitive topics” podcast; and this is also a matter of providing enough time for students to think through all the background information! Or maybe not even provide all the background information, but providing enough time to collect it?)

- Point out that there is a real problem (e.g. by using words like crisis, deaths, poverty)

- Make sure that all roles’ perspectives are somehow included in the problem description, but at the same time that stereotypes are not evoked

- Provide at least one argument for each role in the problem description so students have some place to start from

- Point out where the different roles have conflicting interests so that students cannot just find an uninformed consensus but need to address the actual problems

- Be clear about the context, aim and end product’s audience, so students understand what they are supposed to do and deliver! And that leads us over to the next point:

Alexander & LeBaron (2009) additionally suggest to put something real at stake in the negotiations — like chocolate, or the above-mentioned dinner that needs to be negotiated and prepared. They also suggest to let participants pick roles that resonate with them (but maybe while that is helpful in learning to negotiate, other learning outcomes, like seeing a problem from a different perspective, might require assigning roles that are not immediately aligned with participants’ own values or backgrounds).

Introducing the role play

Very important message when introducing the role play: The purpose of the role play is to learn about a topic, not (judging) the quality of acting! Bonus points if you can explain how the exercise actually contributes to learning (e.g. taking on a different perspective, practising to argue for a point, deepening understanding of a case, …). Also it helps if the focus is less on the outcome than on incremental learning (which, ideally, can be observed in some way).

Alexander & LeBaron (2009) warn of stereotyping, and suggest teaching about stereotyping beforehand so people don’t fall into that trap. Especially, they suggest to “Assign participants roles that do not involve playing ethnocultural identities different from their own. Explore this aspect of cultural difference using alternative experiential activities“.

They also stress that framing matters a lot and suggest that “Engineers may respond well to a request to participate in a simulation” (so much about stereotyping ;-))

Running the role play

When I first thought about running a role play, I thought about all the students being active in the role play, or running it as a “fishbowl“, where arguments can be supported from the outside ring of observers by either changing place with someone on the inside. Alexander & LeBaron (2009) also suggest using fishbowls, but where trainers or actors play the roles that participants then analyse and respond to. That is definitely an interesting idea, too!

Westrup & Planander (2013) point out that, before running a role play, teachers should have thought about strategies for how to act when things don’t go according to plan, like “when students do not want to participate because they believe that the method is childish or unscientific, when students use an exaggerated demeanor, or when embarrassment or tensions between the participants is created“. Developing and refining those strategies can also be a part of preparing the role play in discussion with students, discussing and establishing rules beforehand. Alexander & LeBaron (2009) suggest to “ensure that coaches or instructors are plentiful enough to monitor the dynamics of each group. Intervene if people are getting off the rails in terms of focus or fidelity to the roles“.

Debriefing after the role play

Lastly, Westrup & Planander (2013) make the very important point that “the conversations between the students were a significant part of the role-play. The conversations took place before, during, and after the performances“. This is a very important consideration when using roleplays — the roleplay itself is only as useful as its integration in the wider course. For example, there are many ways to debrief after a role play! Westrup & Planander (2013) used a minute paper directly at the end of the roleplay, followed by more reflective questions at a later date. Alexander & LeBaron (2009) recommend to “Debrief specifically and completely. Resist the tendency to relegate debriefing to an afterthought or a rushed invitation for general comments“. For that, they suggest we “Create space for structured and unstructured reflection. For example, give participants assignments to monitor their application of specific skills practiced in role-plays in actual situations.” Since transfer from the teaching situation into the real world is probably a very important learning outcome, we need to actually support the transfer through specific learning activities where students can practice to integrate the concepts and skills.

[Edit 1/5/2025 to add: Very helpful steps for debriefing in “the Climate Change Playbook”, too!]

And I feel like at this stage, I need to try my hands on actually developing a role play myself in order to make more sense out of what I have read, and to know what more to read about next!

Alexander, N., & LeBaron, M. (2009). Death of the role-play. Hamline J. Pub. L. & Pol’y, 31, 459.

Lönngren, J. (2021). Wicked problems i lärande för hållbar utveckling–Vägledning för att ta fram exempel och problembeskrivningar. Högre utbildning, 11(3).

Westrup, U., & Planander, A. (2013). Role-play as a pedagogical method to prepare students for practice: The students’ voice. Högre utbildning, 3(3), 199-210.