Thinking about sustainable futures, inspired by a recorded lecture by Dougald Hine

Last night I watched a lecture by Dougald Hine. It is part of an online course on Higher Education Didactics for Sustainability that I did not take myself, but that I have been at the fringes off for a while now, looking at the public parts of the course on their learning management system, and reading through their literature list, and talking with participants and facilitators. This lecture was the opening lecture to set the scene, and it was so good that I am now wondering how to implement it in basically all teaching relating to sustainability that I’ll do in the future. Here is a summary of the main points I am taking away from watching it.

One point that I had never considered before is how the way we think about “the future” has changed with the rise of sustainability as a topic. Before, the future was bright and the promise of everything getting better and better. Now considering sustainability, the future requires a massive effort to even just stay where we are at, or actually, requires massive efforts to reduce what we have come to think of as our standard of living. Of course that does something to people, if the general outlook towards the future changes from optimistic to a lot of work to just maintain status quo.

One big problem in conversations around sustainability is that “sustainability” is often reduced to “save the climate”. Which, of course, is important and urgent, but does really not capture the scope of the problem. We have used one way of making that point with the Biodiversity Collage, where climate change only comes in at the very end, after all the drivers of biodiversity loss, all the other processes, and all the consequences are already on the table, and it has become absolutely clear that there is a huge problem that needs fixing even before considering climate change. Dougald Hine makes the same point by suggesting a thought experiment: What if it turned out that the influence of CO2 on atmospheric temperatures turned out to just be a miscalculation somewhere and not actually real — would we then just say “oh, all good now!” and go back to normal, or would there still be a mess to fix? If we focus on climate change, it is easy to fall into a natural science perspective and mostly see the problem as “a bit of bad luck with atmospheric chemistry”, rather than considering what got us into trouble in the first place, which is our way of being in the world, of seeing and treating everyone and everything around us. And the scientific framing of the whole conversation, focussing on technical solutions and policies, distracts us from the conversations we need to have, which are about how to change the way we approach the world, and including everybody, not just STEM professionals and politicians.

Another big problem Hine points out is that many scientists working on topics relating to climate change feel a deep pessimism about the future. Many started their work believing that the world needs saving, and that they and the institutions they work with could and would be a part of the solution, but along the way have lost faith in that the institutions are capable of that. So then, according to that line of thinking, the world is lost. Unless, for some, they jump on wild geoengineering schemes as their only source of hope. And I recognize this description so well from many people I talk with! But then how can people move on from flipflopping between despair and crazy beliefs in technical efforts to working towards a hopeful future?

Hine here refers to an article by de Oliveira Andreotti et al. (2015), where they mapped attitudes towards decolonialization from the soft reform space on the one end, to stepping out of the current game and imagining completely different ways of being on the other. In the soft reform space, where many people are at with regards to climate change, too, we meet the “there isn’t actually a real problem”, to “we can make things good again if individuals change”, to “problems can be fixed by institutional change” attitudes. Then, there is a space where the game is perceived as rigged and rather than everybody learning to play by the rules as before, now the rules need to be changed through radical reforms. Then, there is a space of despair where people recognize the game is broken, but don’t see an alternative; until at the very end of the spectrum, people opt out and come up with the new ways of being. And that is where we need to get to, I think. But that requires giving up the world as we know it for a future we still need to work out.

There is then a really interesting thought about “being born into the end of a world”, when talking about the future does not work any more the way it used to, and people refer to the past rather than the future (as in “make America great again”, or all the Brexit slogans). What to do then? Here, Hine gives the advice to

- Stop worrying about making sense in the logic of the old world

- Look for ways to make “good ruins”: releasing resources from what we use them for now to how we could make them useful in the future, e.g. local food productions around the world that might not be economically viable right now, but that would work if everything else broke down. Hine advises to

- Salvage the good things that we can take with us. Which achievements can we bring?

- Mourn the good things we don’t get to take with us. Tell the stories, and bring them.

- Notice the things that were never as good as we told each other they were.

- Look for the dropped threads from earlier in the story; What old-fashioned practice might actually be resilient?

If we look at sustainability, and teaching for sustainability, this way, it implies that we need to radically rethink everything. We need to bring students on this journey of realizing that we are at the end of the world as we know it, and support them while mourn the future they were promised but won’t get. And not just students, everybody. And for that, we need to start thinking through those 4 points, individually and in conversations with each other. What can we bring with us, and what do we need to let go of? What might be easy to let go of because it wasn’t even that good in the first place? And where can we pick up ideas that were discarded throughout history but that are useful now for this unknown future? It is scary and daunting and not something that we can do alone. So let’s build the communities we need!

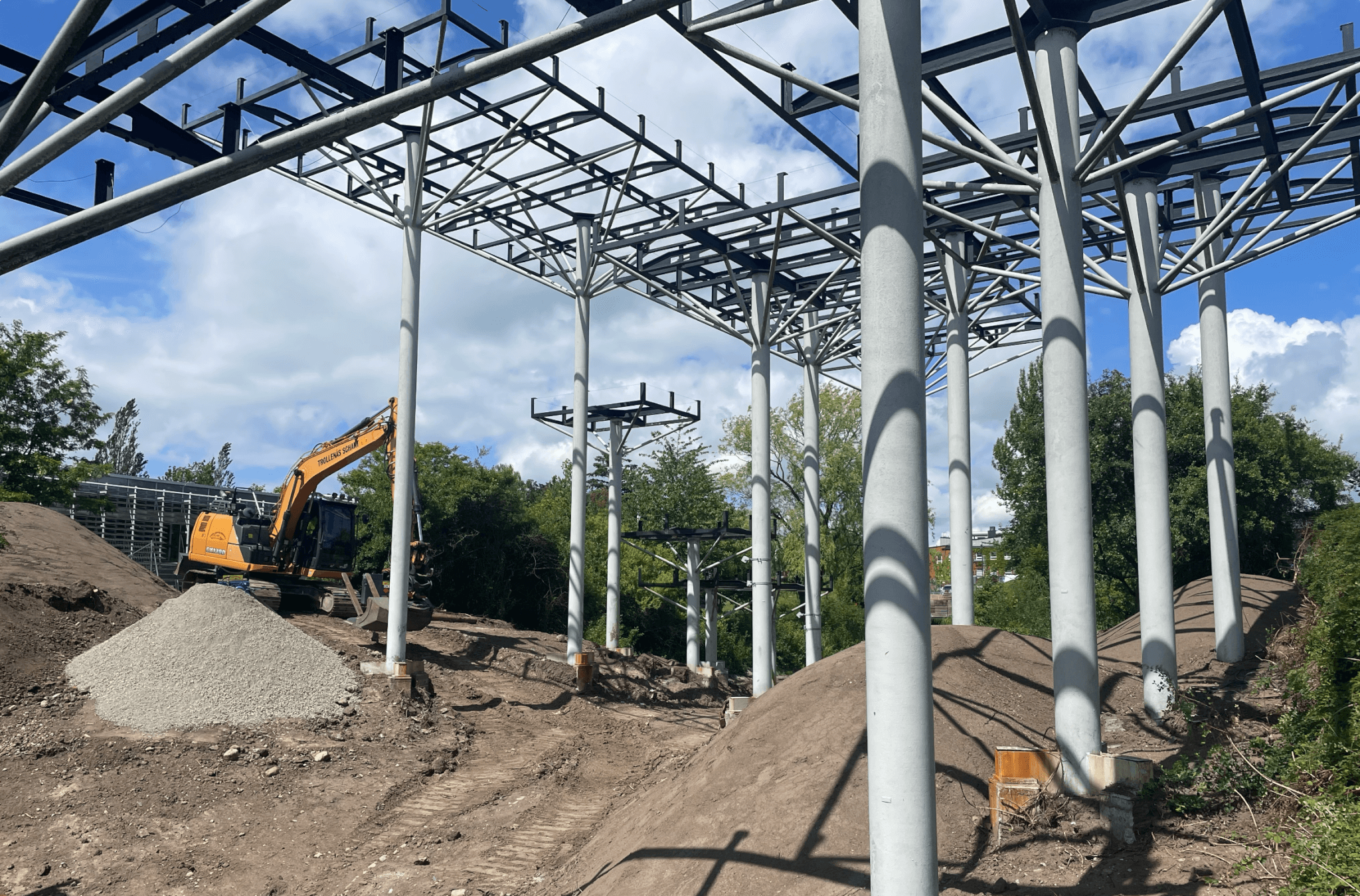

Featured image: Next to my office, there are two ponds with, at best, questionable water quality. And now there will soon be a surface storm drain connecting them with hopes of collecting more rain water in the top pond, the overflow then entraining a lot of oxygen and bringing it into the lower pond, thus improving water quality everywhere. That seems very optimistic and we’ll see how it turns out!

de Oliveira Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, education & society, 4(1).