Currently reading Part II of the book “Sustainable Development Teaching – Ethical and Political Challenges”, edited by Van Poeck, Östman, Öhman (2019)

Following up on “PART I: Education and the challenge of building a more sustainable world” that I summarized here, here comes

PART II: Choosing teaching content and approaches

The first chapter in this part is about

“sustainable development teaching in view of qualification, socialisation and person-formation“

by Van Poeck and Östman.

In this chapter, the authors elaborate on the three functions of teaching — qualification, socialisation and person-formation — mentioned already in the previous chapter, and give examples of how these functions are represented in the SDGs:

- Qualification is about learning the knowledge and skills that are required in the future (work) life, for example understanding relationships between poverty and human rights, communicating about hunger, being able to plan, implement, evaluate and replicate water quality measures.

- Socialisation is about learning values, attitudes, norms and worldviews of the governing group. This can be done explicitly, for example by teaching about democracy, but it is always present implicitly in, for example, the choice of content that is deemed important, the examples being presented, etc. In the SDGs, there are explicit socialisation goals, e.g. about values like justice and equality, about attitudes: feeling empathy and solidarity with people who are different and discriminated against, feel responsibility, and about norms and worldviews: “maintaining a vision of a just and equal world”

- Person-formation is about developing people, about becoming, in the Bildung sense. This is also represented in the SDGs, for example as “critical thinking competency”, or being able to reflect on your own identity, belonging to groups, etc.. Person-formation sometimes happens through identification, taking on roles offered as for example someone working in a certain profession or someone who behaves in a certain way, or subjectification, basically the opposite of socialisation, when someone develops as an independent individuum and rejects pre-defined roles. This process can be supported through exercises or happen spontaneously in response to experiences, but it’s difficult to foresee and plan.

Traditionally, those three functions are thought to be taught separately at different times, on different topics, often by different people, but the authors argue that this is not possible. Teaching qualification, i.e. skills and knowledge, will also come with the “companion meaning” of socialisation that offers typical roles for how to relate to it, and underlying worldviews. And if we acknowledge this, we can integrate the three functions in a planned, deliberate way.

The next chapter is about

“Different teaching traditions in environmental and sustainability education”

by Öhman and Östman.

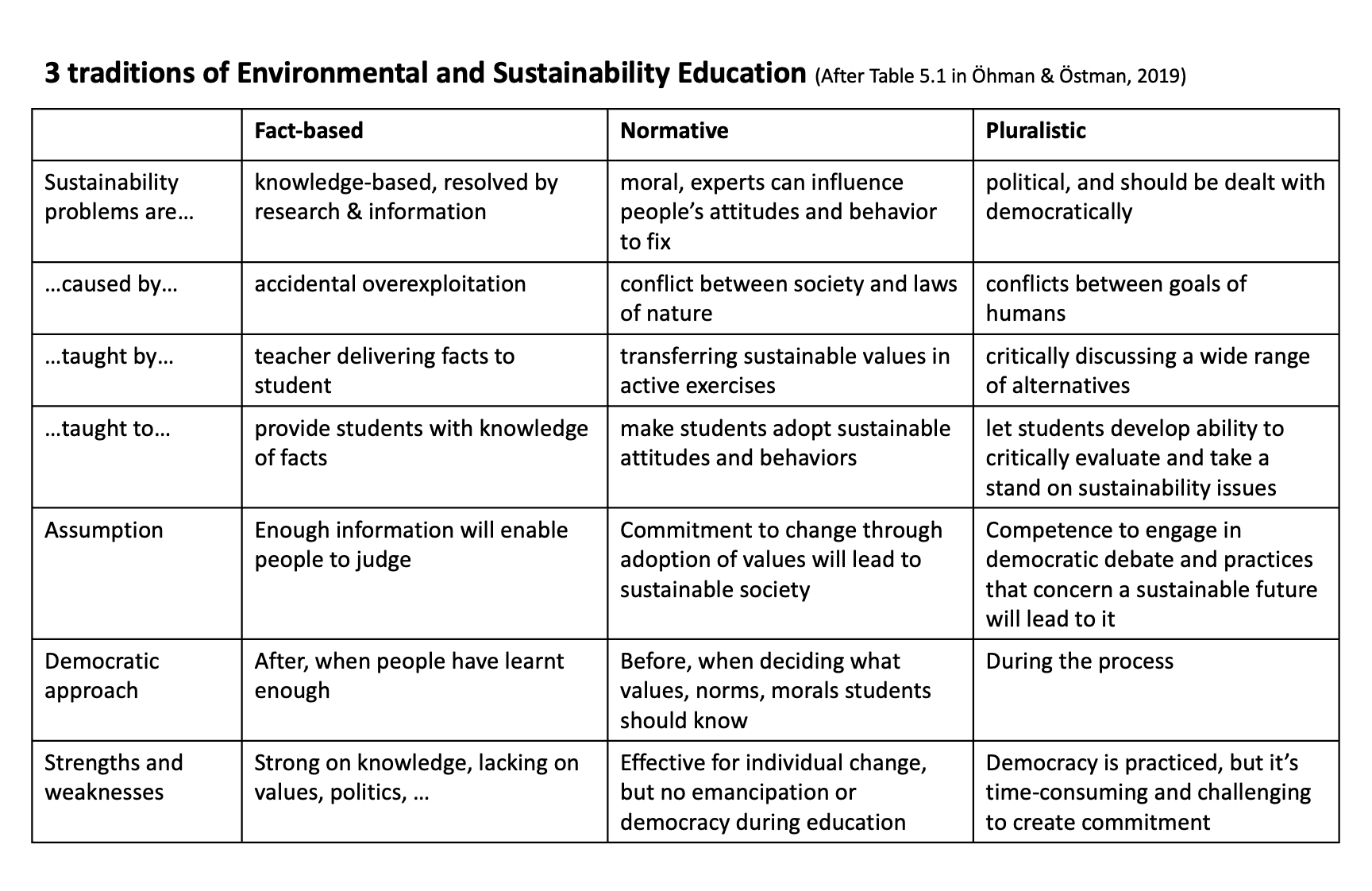

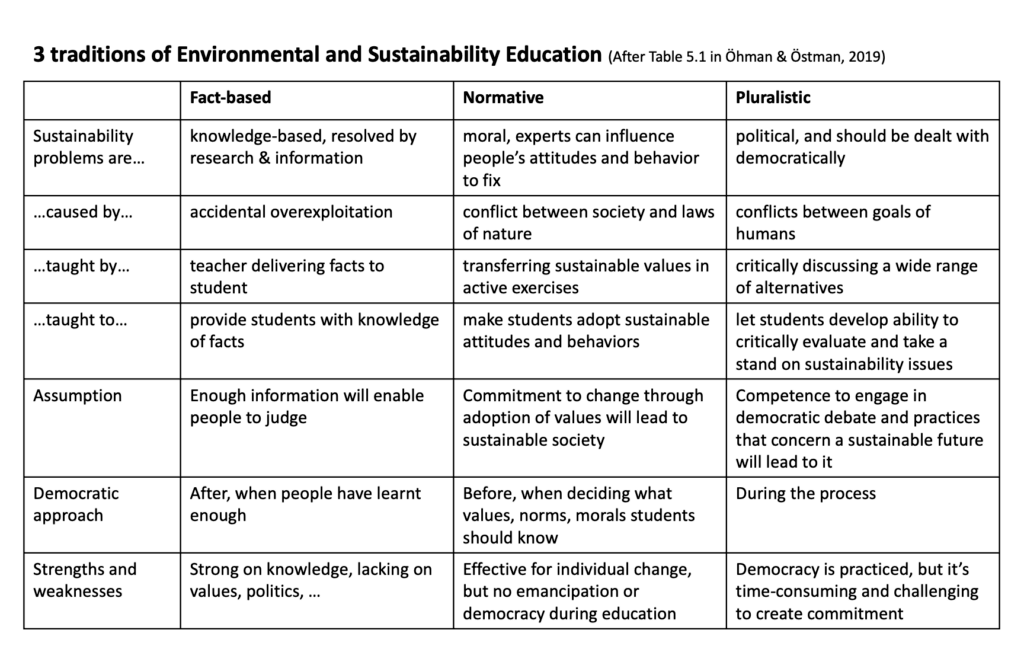

Within disciplines, there are usually strong traditions of how different subjects are being taught. Often, those traditions are so deeply entrenched that it is hard to imagine (and even harder to accept) that there might be other ways of teaching the same content. In this chapter, three different traditions (fact-based, normative, and pluralistic) are presented with the intention of helping the readers choose the appropriate approach consciously rather than just following a tradition. The discussion follows two premises: That sustainability issues are value issues and that they should be dealt with democratically.

The three traditions are different in how they approach sustainability (how much trust is put in science, how much changes we should make as individuals, how much changes overall are necessary), didactics (the motives, e.g. preserving culture vs creating change; content, e.g. what is most central; and methods used in education, e.g. do we see the student as passive or active), facts and values (should we teach values, or just facts, and do facts exist without values?), and democracy and education (paradox: we want autonomous subjects that still follow our basic values and norms). With this in mind, here are the three traditions:

The fact-based tradition sees sustainability as a knowledge-based problem. If everybody knew more, we could find technological solutions to the problem. Therefore, in this tradition teaching is focussed on facts, mostly in STEM subjects, and to some extent labs and field trips; and student interests can be incorporated. The assumption here is that the scientific method is value-free, therefore values are seen as subjective and belonging in students’ private lives, not class. When the education is completed, students have learned enough to become democratic citizens.

The normative tradition sees the moral implications in scientific findings, and experts from scientific fields should advise us on how to act. It is an individual responsibility to live a sustainable life based on the expert advice. Value conflicts are solved through discussion between experts and politicians, and trickle then down into policy documents and syllabi, but lessons aim to connect it to students’ real lives and experiences in group- and problem-based approaches, often in the field and co-created.

The pluralistic tradition acknowledges the conflicts between interests, values and ideologies on almost all issues — the interpretation of facts, what effective or suitable solutions might look like, etc.. Science can inform, but not guide decisions since so many stakeholders are involved. In teaching, this means highlighting different views and values that can and should be rationally and openly, critically and democratically discussed. In teaching, discussion is quality-controlled by the teacher, and methods like role play or panel debates help practice democratic processes.

As teachers, we of course come from within one of those traditions, and work in a context that has its tradition. So how do we choose how to teach? Looking back at the premise that sustainability issues are value issues and that they should be dealt with democratically, each tradition has strengths and weaknesses.

The fact-based tradition has the strength that students come out with a solid scientific basis, know how to fact-check and evaluate facts, and how to work with facts. It has the huge disadvantage that there has been no discussion of values or differing perspectives, and this leads to authority being assigned to the person with the most facts (the teacher) over everybody else. So there is no practicing of democracy or co-creation, and instead a belief in a society run by experts, and technological solutions.

The normative tradition encourages specific views and moral responsibilities to problems. This can be very effective in changing individual behavior and creating committed groups working towards common goals. But it also gives a large power and responsibility to the teacher to teach the correct values and norms, which doesn’t exist in such an absolute form, but this might not always be discussed. The focus here is on socialization, not subjectification (as discussed here), as the teacher is the moral authority who knows best, and everybody else follows. This is not democracy.

The pluralistic tradition makes students aware of all the different values and interests involved in the debate, including the students’ own. Students develop their abilities to discuss, argue and listen, reflect, find their own position, and engage in democratic processes. However, this takes a lot of time and the outcomes are unpredictable. The teachers need to encourage both students’ free will and at the same time strong commitment, they facilitate the catalyst in a process.

All this is very nicely summarized in their table 5.1, which I am showing below (since I had to re-do it anyway in order for my brain to process it properly…)

Next, it is Chapter 6 by Öhman & Östman, on

“The ethical tendency typology”

One really scary aspect, I find, of teaching about sustainability is that what we think is universally good and right is not actually universal, so we often end up in disagreements about how we should approach a specific situation based on value judgements that we rarely articulate, and that I don’t really feel equipped to, either. But the authors present definitions that help teachers distinguish between different ways students express ethical tendencies:

Moral reactions — spontaneous reaction to events where we feel personally affected — in the real world or, for example, in books — based on gut feeling of, for example, care or disgust

Norms for correct behaviour — social rules of how we should act that we learn in response to others, relating to a specific activity or community, and that make us an accepted member of that group

Ethical reflections — rationally and systematically generating abstract general rules, norms, or principles, considering reasons for and consequences of our actions

If we want to teach using a pluralistic approach to sustainability (see more about that in the chapter above), we need to expose students to a variety of situations where they experience different expressions of what’s right and good in different contexts, and where they have to relate to those. We should create opportunities for students to express and share their moral reactions, and we need to then take them seriously and help them become aware of, and react to, possibly conflicting reactions that others show. When it comes to norms, we can again create opportunities to discuss both norms and motives behind them. Knowing what the norms in a certain community and situation are does not — and should not — mean having to accept or follow them, just being able to consciously decide for or against it. We also need to create room for ethical reflections, knowing that we should not claim that some principles are more correct than others, and also that there is no easy answer for dilemmas, and that answers will likely only come as we live through them, and maybe not even then.

So how do we facilitate those kinds of discussions in class? I am hoping that the next chapter will give us some ideas, but for a summary of that one, you will unfortunately have to wait for the next blog post, because I unfortunately also have other stuff that I need to do (although this is super interesting and I would love to focus on this exclusively for the next couple of days!)

Van Poeck, K., Östman, L., & Öhman, J. (Eds.). (2019). Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351124348

Currently reading Part III of the book "Sustainable Development Teaching - Ethical and Political Challenges", edited by Van Poeck, Östman, Öhman (2019) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] and the challenge of building a more sustainable world” that I summarized here, and the first part and second part of the summary of “PART II: Choosing teaching content and […]