The learning styles myth (based on Pashler et al., 2008; Nancekivell et al., 2020)

One idea that I encounter a lot in higher education workshops is the idea of learning styles: that some people are “visual learners” that learn best by looking at visual representations of information, and other people that learn best from reading, or from listening to lectures, and that those are traits we are born with. When I encounter these ideas, they usually come with the understanding that we, as teachers, should figure out students’ learning styles and cater to the individual students’ styles. Which — even though I haven’t seen that actually happening in practice very much — if we take it seriously, obviously adds a lot of pressure and work that is taken on with the best intentions of supporting students in the best possible way.

But learning styles are a bit of a myth. When you ask people, yes, they will tell you about their preferences for learning. And certainly there are people who work better with one representation than with another. But that in itself is not enough to support the whole theory of learning styles.

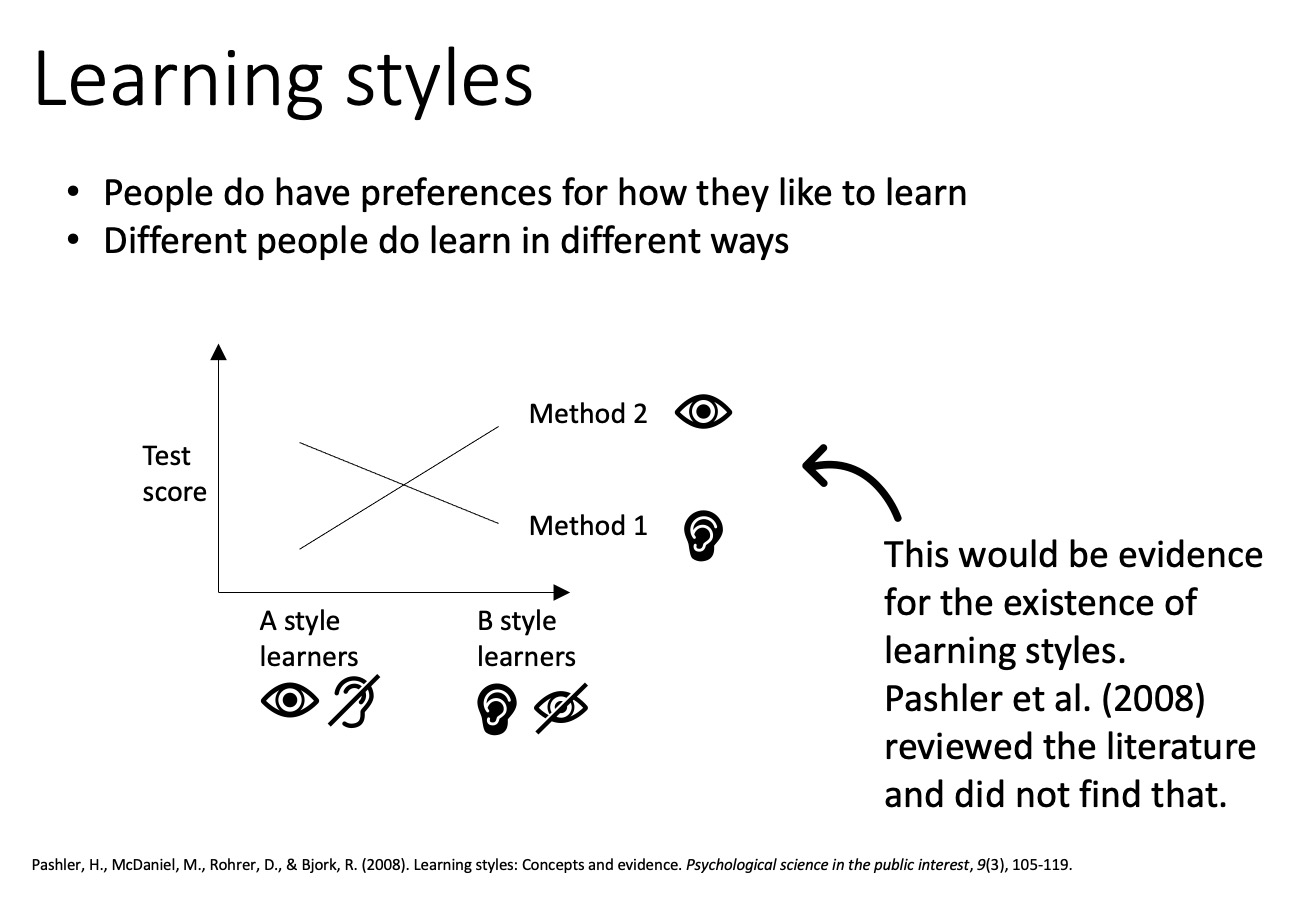

In a review article, Pashler et al. (2008) show what kind of studies we would need to conduct in order to conclude that learning styles actually exist: We would have to separate a group of students based on their leaning styles and then teach part of each group with one method designed for one of the learning styles, and another part of the group with another method designed for the other learning style, and test both groups with the same test.

Pashler et al. (2008) then show what would count as evidence for the existence of learning styles and what would not (which is one reason for why I enjoyed reading the article so much, check out their Figure 1!!): Only if students with one learning style learn best from the method designed for their learning style, and students with the other learning style learn best from the method designed for them, we can conclude that students should be taught using the method that works with their learning style. And Pashler et al. (2008) state that they could not find studies showing that kind of evidence. If one method works better for all students with one learning style but the other method does not work better for students with the other, then we might still consider offering different methods to different people, but clearly the learning style isn’t the criterium we should be using to assign methods.

Then why do so many people believe in learning styles that it’s worth building an entire industry around them? It seems that the myth that our learning style is something we are born with is really common; especially in educators working with young children (Nancekivell et al., 2020). What that means it that the idea that “you are someone who learns best from looking at pictures” or “you are someone who learns best from listening” is propagated from kindergarten teachers to really young kids, and that we are likely to grow up with a belief about how we learn best based on what we were told when we were young. That belief is usually not challenged (and why would we challenge it?), and since it’s a framework that we have accepted for us and others, we are likely to start diagnosing learning types in others later on and thus keep the myth going. Since the learning style idea is never challenged, we are likely to adapt inefficient strategies based on our belief on what our learning style is.

What does that then mean for which methods we should be using in teaching? Pashler et al. (2008) conclude that we should focus our time and energy on methods for which there is empirical evidence of effectiveness (see for example here). Mixing up representations and including visual, auditory, tactile, … learning is probably still good — only tying it to specific learners and suggesting to them that they are inherently better at learning from one representation over all others, is not. Or if it is, there is no empirical evidence of it.

Nancekivell, S. E., Shah, P., & Gelman, S. A. (2020). Maybe they’re born with it, or maybe it’s experience: Toward a deeper understanding of the learning style myth. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(2), 221.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological science in the public interest, 9(3), 105-119.

Currently reading: "Do Learners Really Know Best? Urban Legends in Education" by Kirschner & van Merriënboer (2013) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] is no evidence that learning styles exist beyond learning preferences (see also my blog post on The learning styles myth (based on Pashler et al., 2008; Nancekivell et al., 2020), who make a very clear argument for why there is no evidence whatsoever for learning styles). Of […]