I got permission to publish Kjersti Daae‘s iEarth conversation on teaching (with Torgny Roxå and myself in April 2021) on my blog! Thanks, Kjersti :-) Here we go:

I teach in an introductory course in meteorology and oceanography (GEOF105) at the geophysical institute, UiB. The students come from two different study programs:

Most students do the course in their third semester. They have not yet learned all the mathematics necessary to dive into the derivation of equations governing the ocean processes. Therefore, we focus on conceptual knowledge and understand the governing ideas regarding central ocean processes, such as global circulation and the influence of Earth’s rotation and wind on the ocean currents. The students need to learn how to describe the various processes and mechanisms included in the curriculum. I, therefore, use voting cards to promote student discussions during lectures.

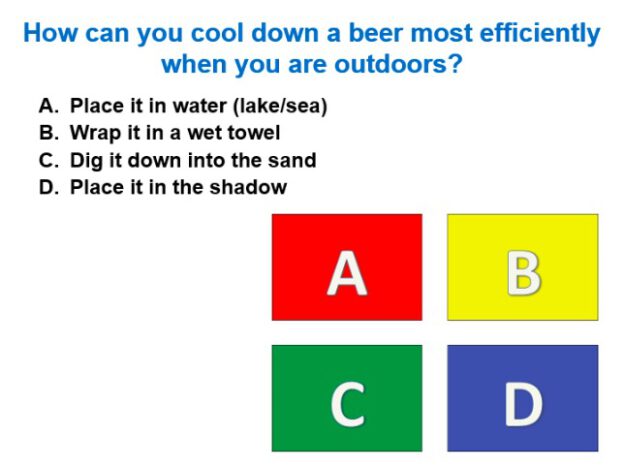

I first heard about voting cards from Mirjam’s blog “Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching”. The method is relatively simple. You pose a question with four alternatives A,B,C,D, accompanied by different colours for easy recognition. The students have a printout each with the four letters on it.They spend a few minutes thinking about the question and prepare their answer. Then they fold their paper so that only one letter/colour shows, and hold it up and provide direct feedback to the teacher. The questions can, among others, be used to checking if the students understand a concept or let the students guess the outcome of something they haven’t learned yet.

However, I prefer to use voting cards to promote discussions among peers. This procedure is following the Think-pair-share method developed by Lyman (1981). By carefully selecting alternative answers, I can make it hard for the students to choose the correct answer, or the answers can be formulated so that the students can argue for more than one correct answer. When the students hold up their answers, they can look around at the other students’ responses and find someone with a different response than themselves. Then they can pair up and discuss why they answer differently and see if they can agree on one common answer before sharing their opinion with the rest of the class. During this exercise, the students practice talking about science and arguing for various answers/outcomes based on the voting cards’ questions.The exercises serve at least two purposes:

- The student practice answering/discussing relevant questions for the final exam.

- The students get active instead of listening passively to the lecturer.

Usually, I can see the students becoming very tired after 10-15 minutes of passive listening. These voting questions “wake up” the students, and after one such question, they tend to stay focused for another 10-15 minutes.

I think the voting cards work really well. When I display a question, the students usually move from a relaxed position to sitting more straight and preparing for being active. I can hear them discussing what they are supposed to. I also get very good feedback and responses in whole-class discussions/summaries following the discussions in pairs. Such summaries are especially interesting if multiple answers can be correct, depending on how the students argue. I can select responses from students based on their visible letters and make sure we can hear different solutions to the same question. During a semester, I see a clear development in the way students reflect on the various questions and express critical thinking governing oceanographic processes. The exercises show the students how important argumentation is. An answer with a well-founded argumentation and critical thinking is worth much more than just the answer/letter. My observation is consistent with Kaddoura (2013), who found that the think-pair-share method increased nursing students’ critical thinking.

Lyman, F. (1981). “The responsive classroom discussion.” In Anderson, A. S. (Ed.), Mainstreaming Digest, College Park, MD: University of Maryland College of Education.

Kaddoura, M. (2013). «Think Pair Share: A Teaching Learning Strategy to Enhance Students’ Critical Thinking», EducationalResearchQuarterly, v36 n4 p3-24