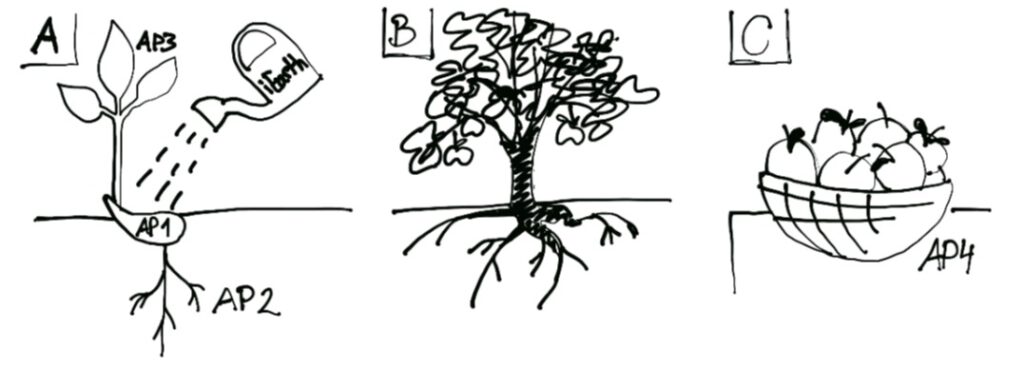

One of iEarth’s stated goals is to develop “local field laboratories” at at least three out of its four member institutions: UiB, UiO, UiT, and UNIS. But what exactly a “local field laboratory” is, and why it actually should enhance learning, is yet to be figured out. In a discussion with iEarth colleagues yesterday, we talked about many benefits of local field laboratories (a term which, again, isn’t clearly defined yet). I am elegantly skipping over the step 1 of the action plan, which would be to do a comprehensive literature search on the topic, and am just documenting my own thoughts after that meeting.

Let’s start out from what we know is necessary for intrinsic motivation, and hence for student learning, namely continuously feeling autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). How can we use interdisciplinary, local field sites to create conditions in which those are experienced?

— Note: ultimately, whether or not those conditions are created will of course depend on how a course is designed and conducted much more than on where it happens! —

Fostering a feeling of autonomy

A feeling of autonomy means that students feel that they have (some) choice over what they do when and where. This can mean many things, of course, and a couple of ideas are provided here.

How a local field laboratory can help foster a feeling of autonomy

Autonomous access: If the local field laboratory is close to campus, students can access (and leave!) it by themselves, possibly by foot, bike, car, public transport, rather than for example a plane. This means they can – at least to a degree – adapt it to their needs: arrive a bit earlier or leave a bit later. It also means that if that they really want to leave a situation they are not comfortable in, they can do that at any time (and are not stuck in some remote location with whoever makes them uncomfortable).

Depending on the setup, it might be possible to access the local field laboratory outside of normal hours, for example for students to catch up on experiments that they missed because of sickness, or to do extra projects because they are curious. This also gives a lot of flexibility to accommodate students that cannot be present during scheduled times.

Low psychological threshold: Field trips – especially the first one to a new location or with a new group – can be scary situations. If the local field laboratory is located close to campus, students stay in an environment where they are familiar with the general culture, language, … This likely means that they feel more confident, and thus more autonomous, in that setting.

Low financial burden: In a local field laboratory close to campus, students are likely to already have appropriate personal equipment (for example a rain jacket appropriate for local climate) rather than having to purchase it for a new-to-student-and-never-to-be-visited-again location. This lowers one potential threshold for participation, giving the students autonomy.

Accessibility: A local field laboratory close to campus is more accessible than having to hike and carry equipment in difficult conditions. A local field laboratory close to campus is NOT accessible to everyone just by virtue of its location though, but it might be easier to make it such.

How using the same local field laboratory with many different disciplines and courses can help foster a feeling of autonomy

More choice of potential research questions: If the local field laboratory is used by many different disciplines or courses, there will be more equipment available for experiments, and more diverse data from previous experiments (if there is a good data storage system). This makes the potential student research questions more interesting and provides a wider choice (if the teachers are flexible enough to allow it).

Accessibility: As stated above, accessibility does not happen by itself, but needs to be considered and planned for. But if there are many students using the same local field laboratory, there might be more resources invested into making sure that the local field laboratory is actually accessible for everybody, and also teachers can build on other teacher’s experiences and good ideas.

Fostering a feeling of competence

Feeling competent means receiving positive feedback: Either external through teachers, friends, family, or an audience on social media, or just by succeeding at doing something.

How a local field laboratory can help fostering a feeling of competence

Transfer: Learning is always situated in a specific context, and the transfer to other contexts is not easy. If the local field laboratory is located close to campus, students can transfer more easily into their own life as it is the same type of environment they spend their whole lives in, thus re-prompting the topic they learned at in that environment over and over again, making them see the world around them with the eyes of an expert – an experience of competence!

Not only one-off: Since the local field laboratory is so close to campus, students can revisit the lab if they want and either repeat or do more. They can also bring friends and/or family to show what they have learned, and have their expert status confirmed. More training in being in the lab and talking about lab content is always practising both lab and science communication skills.

A local field laboratory close to campus can also be used as a red thread throughout the curriculum: the lab can be visited repeatedly over several courses, each time going into more depth, building more competence.

How using the same local field laboratory with many different disciplines and courses can help fostering a feeling of competence

Relevance & context: In a local field laboratory that is used by other courses and disciplines, students can more easily recognise how their own discipline fits into and contributes to a larger scientific context.

Interdisciplinarity: If the local field laboratory is used as a red thread throughout the curriculum, different aspects of the same site can be explored over several courses (geology, soil, climate, weather, plants, …)), thus building interdisciplinary aspects over time, increasing competence by exploring different facets of the same site.

Fostering a feeling of relatedness

Relatedness is the feeling of being part of a supportive group. That doesn’t mean the group has to be around someone all the time, but they have to know that it is there.

How a local field laboratory can help fostering a feeling of relatedness

Contribution to local community: If the local field laboratory is located close to campus, it is also located in the community where students live. Their research can thus have a direct relevance for their community, which can help them feel more connected both by doing something for the community as well as by sharing their learning with members of that community and getting their feedback.

Reducing the carbon footprint: Doing the slightly less exciting field lab that doesn’t go to an exotic location contributes to lowering our carbon footprint, which students might perceive as their personal contribution to something bigger than themselves.

How using the same local field laboratory with many different disciplines and courses can help fostering a feeling of relatedness

Larger context: If the local field laboratory is set up well, there is an overarching theme of all the measurements that are being taken, so that everybody is contributing to something beyond just doing their laboratory results, but much bigger, beyond their own discipline.

Interdisciplinarity: If several courses are at the field site simultaneously, students get to meet students and staff from other disciplines (formally in course context, or informally over dinner) and build a larger scientific network for themselves.

Other considerations that might be relevant to universities

Of course optimising student learning is not the only consideration that universities have, and it would be naive to assume that it was. So here are a couple of other relevant considerations:

Benefits of local field laboratories

- lower travel costs

- lower risks connected with long travel or dangerous field sites that the university might have to mitigate

- easier logistics because of shorter transport that isn’t going across borders or oceans

- lower carbon footprint!!

- the field laboratory can be used for outreach “in the field”, inviting people into authentic research situations

Benefits of using the same local field laboratory with many different disciplines and courses can help

- synergies: using equipment, buildings, … for multiple purposes

- easier logistics since everything just needs to go to one place

- red thread in curriculum: teachers meet (formally or informally), talk more, improve coherence between courses / find more interesting interdisciplinary questions

Is that really the full story?

Of course, many of these arguments are just one side of a coin, and local field sites might be best suited to undergraduate education and less so for advanced courses. Maybe one of the learning outcomes is for students to learn about dealing with logistics in a part of the world where everything works differently from what they are used to, and where they don’t speak the language. Or some things just cannot be taught in a certain area because that process just does not happen there. But then those arguments should be made specifically, and weight against the benefits listed above. But I think it’s definitely worthwhile to consider local field laboratories as an alternative to many established field trips to far-away locations: for carbon-footprint reasons just as much as for all the reasons listed above!

What are your thoughts on local field laboratories? And what references should I start with when I finally will have the time to start reading on the topic?

Reference

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68.