You probably know that I have recently changed my research focus quite dramatically, from physical oceanography to science communication research. What that means is that I am a total newbie (well, not total any more, but still on a very steep learning curve), and that I really appreciate listening to talks from a broad range of topics in my new field to get a feel for the lay of the land, so to speak. We do have institute seminars at my current work place, but they only take place like once a month, and I just realized how much I miss getting input on many different things on at least a weekly basis without having to explicitly seek them out. To be fair, it’s also summer vacation time and nobody seems to be around right now…

But anyway, I want to talk about why it is important that people not only of different disciplines talk, but also people from within the same discipline that use different approaches. I’ll use my first article (Simulated impact of double-diffusive mixing on physical and biogeochemical upper ocean properties by Glessmer, Oschlies, and Yool (2008)) to illustrate my point.

I don’t really know how it happened, but by my fourth year at university, I was absolutely determined to work on how this teeny tiny process, double-diffusive mixing (that I had seen in tank experiments in a class), would influence the results of an ocean model (as I was working as student research assistant in the modelling group). And luckily I found a supervisor who would not only let me do it, but excitedly supported me in doing it.

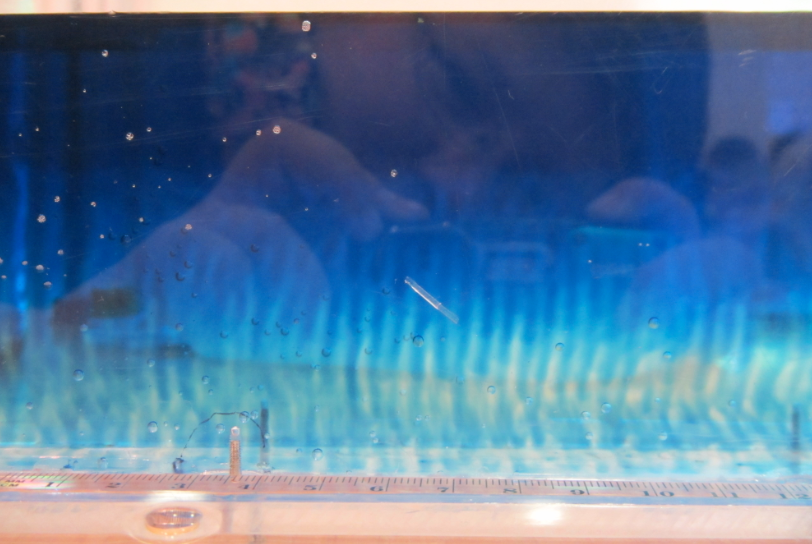

Double-diffusive mixing, for those of you who don’t recall, looks something like this when done in a tank experiment:

And yep, that’s me in the reflection right there :-)

Why should anyone care about something so tiny?

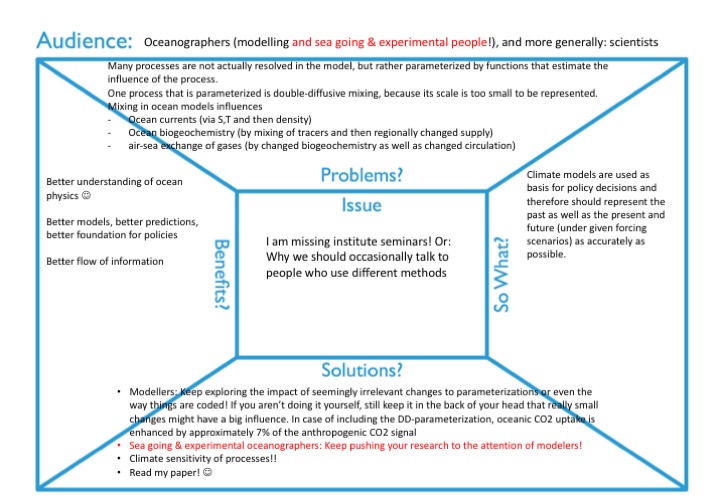

Obviously, there is a lot of value in doing research to satisfy curiosity. But for a lot of climate sciences, one important motivation for the research is that ultimately, we want to be able to predict climate, and that means that we need good climate models. Climate models are used as basis for policy decisions and therefore should represent the past as well as the present and future (under given forcing scenarios) as accurately as possible.

Why do we need to know about double-diffusive mixing if we want to model climate?

Many processes are not actually resolved in the model, but rather “parameterized”, i.e. represented by functions that estimate the influence of the process. And one process that is parameterized is double-diffusive mixing, because its scale (even though in the ocean the scale is typically larger than in the picture above) is too small to be represented.

Mixing, both in ocean models and in the real world, influences many things:

- By mixing temperature and salinity (not with each other, obviously, but warmer waters with colder, and at the same time more salty waters with less salty), we change density of the water, which is a function of both temperature and salinity. By changing density, we are possibly changing ocean currents.

- At the same, other tracers are influenced: Waters with more nutrients mix with waters with less, for example. Also changed currents might now supply nutrient-rich waters to other regions than they did before. This has an impact on biogeochemistry — stuff (yes, I am a physical oceanographer) grows in other regions than before, or gets remineralized in different places and at different rates, etc.

- A change in biogeochemistry combined with a changed circulation can lead to changed air-sea fluxes of, for example, oxygen, CO2, nitrous oxide, or other trace gases, and then you have your influence on the atmosphere right there.

What are the benefits of including tiny processes in climate models?

Obviously, studying the influence of individual processes leads to a better understanding of ocean physics, which is a great goal in itself. But that can also ultimately lead to better models, better predictions, better foundation for policies. But my main point here isn’t even what exactly we need to include or not, it is that we need a better flow of information, and a better culture of exchange.

Talk to each other!

And this is where this tale connects to me missing institute seminars: I feel like there are too few opportunities for exchange of ideas across research groups, for learning about stuff that doesn’t seem to have a direct relevance to my own research (so I wouldn’t know that I should be reading up on it) but that I should still be aware of in case it suddenly becomes relevant.

What we need is that, staying in the example of my double-diffusive mixing article, is that modellers keep exploring the impact of seemingly irrelevant changes to parameterizations or even the way things are coded. And if you aren’t doing it yourself, still keep it in the back of your head that really small changes might have a big influence, and listen to people working on all kinds of stuff that doesn’t seem to have a direct impact on your own research. In case of including the parameterization of double-diffusive mixing, oceanic CO2 uptake is enhanced by approximately 7% of the anthropogenic CO2 signal compared to a control run! And then there might be a climate sensitivity of processes, i.e. double-diffusive mixing happening in many ore places under a climate that has lead to a different oceanic stratification. If we aren’t even aware of this process, how can we possibly hope that our model will produce at least semi-sensible results? And what we also need are that the sea going and/or experimental oceanographers keep pushing their research to the attention of modellers. Or, if we want less pushing: more opportunities for and interest in exchanging with people from slightly different niches than our own!

One opportunity just like that is coming up soon, when I and others will be writing from Grenoble about Elin Darelius and her team’s research on Antarctic stuff in a 12-m-diameter rotating tank. Imagine that. A water tank of that size, rotating! To simulate the influence of Earth’s rotation on ocean current. And we’ll be putting topography in that! Stay tuned, it will get really exciting for all of us, and all of you! :-)

P.S.: My #COMPASSMessageBox for this blogpost below. I really like working with this tool! Read more about the #COMPASSMessageBox.

And here is the full citation: Glessmer, M. S., Oschlies, A., & Yool, A. (2008). Simulated impact of double‐diffusive mixing on physical and biogeochemical upper ocean properties. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 113(C8).